Burnley have never been a fashionable club, yet they took English football by storm in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

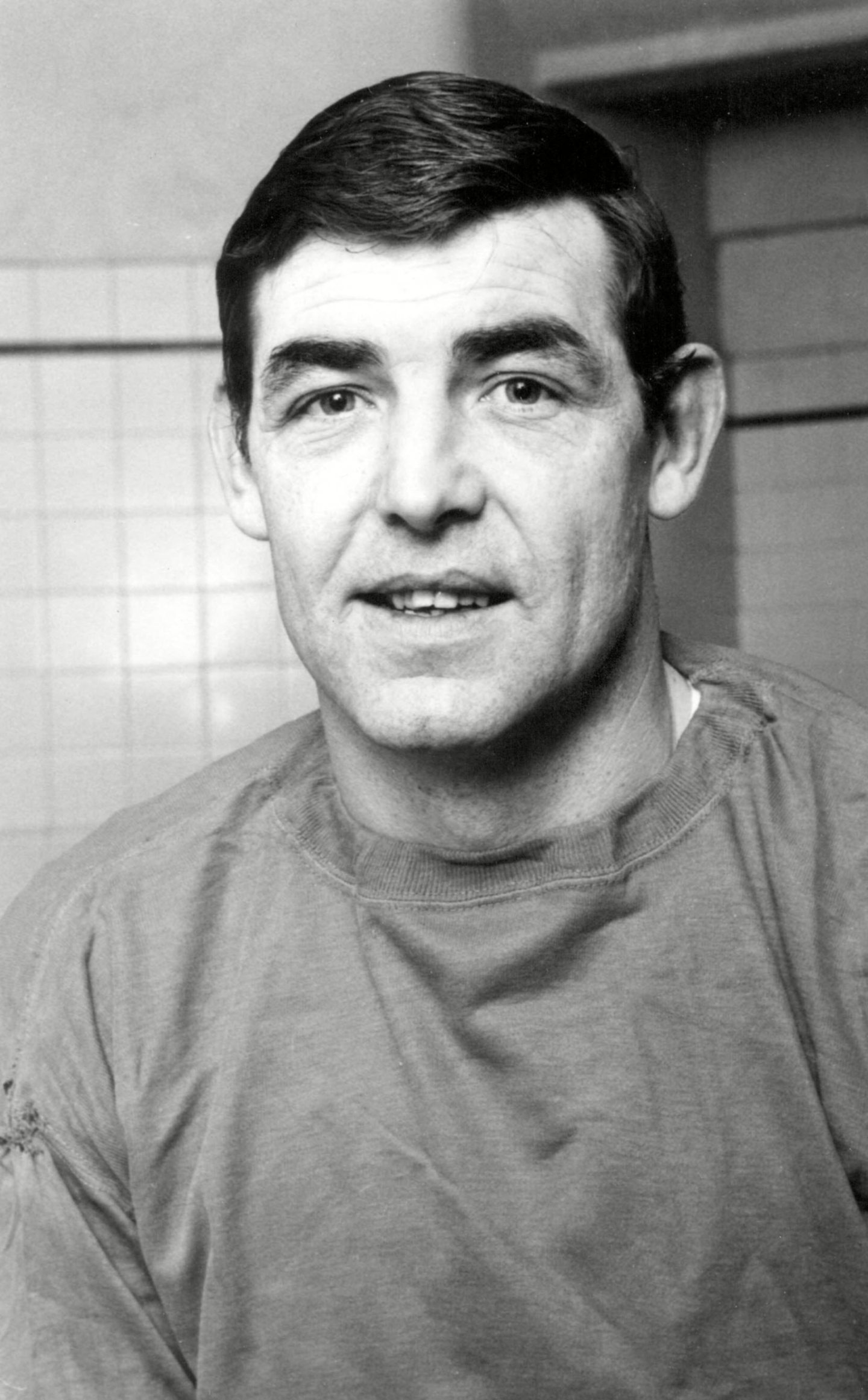

And they did it with an Aberdeen bricklayer, Adam Blacklaw, who ensured there were no gaps in the wall for opponents throughout his illustrious career.

Their League title victory in 1960 remains one of the most remarkable feats in the sport’s history. Burnley had less money and fewer fans than most of their rivals, but they triumphed over Manchester United, Spurs, Wolves and the rest, not with a defensive, up-and-at-em mentality, but with a fluid, continental-style philosophy which gained them many admirers.

Jimmy Greaves recalled: “I wanted to applaud their artistry. In an age when quite a few teams believed in the big boot, they were a league of gentlemen.”

And they were boosted every step of the way by the dynamism and athleticism of Blacklaw, who subsequently earned Scotland selection and was involved in one of the national side’s most resplendent performances in 1963.

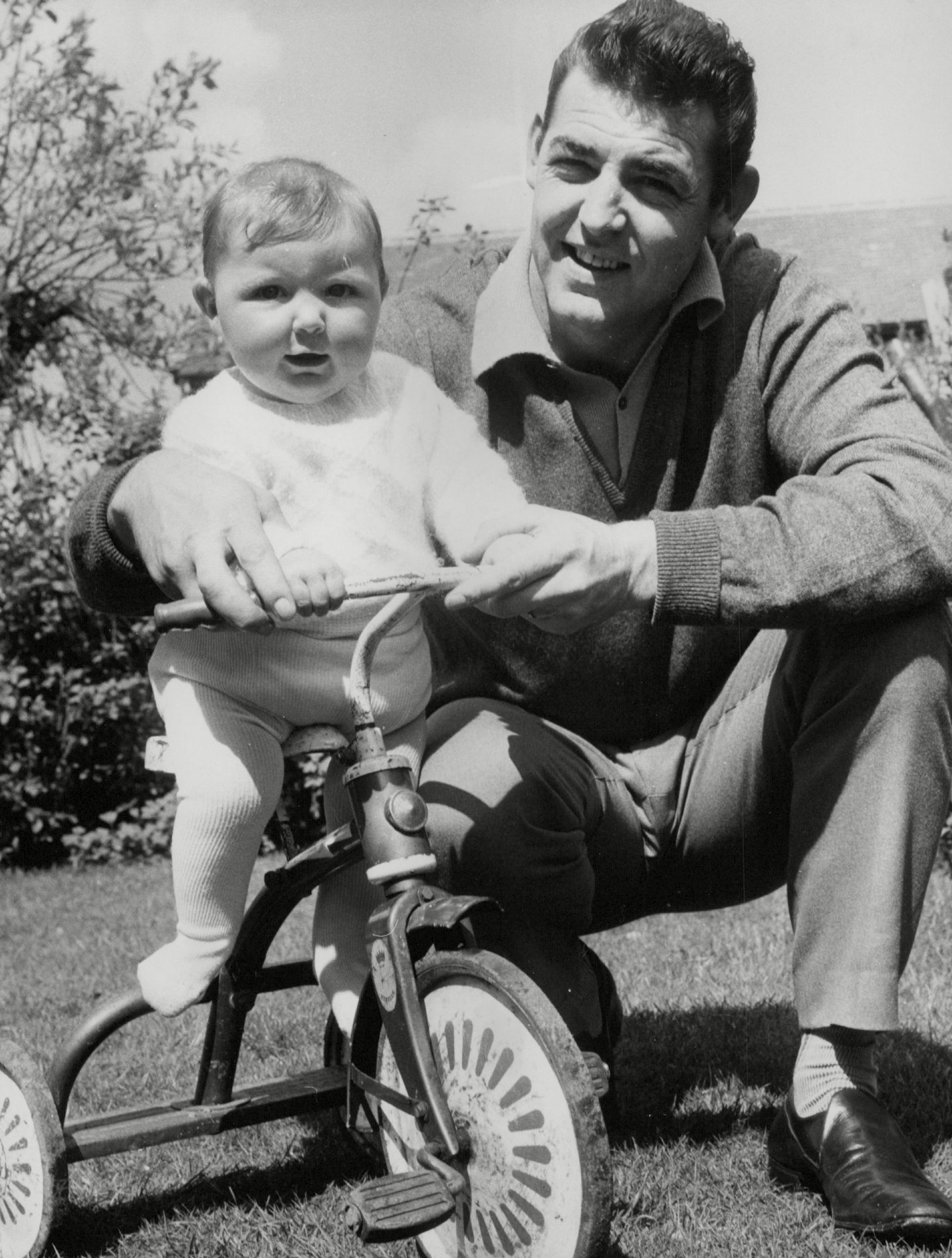

The young Adam grew up in Aberdeen during the Second World War and, from the outset, was fitba-daft, encouraged in his love for the game by his father, Jimmy, who was a local hero with Banks o’Dee.

As he told the Press and Journal: “The only ambition I had as a kid was to follow my dad into football and, thankfully, I was able to make a living from it. All I did as a youngster was kick a ball against the wall and, despite the cobbles, me and my pals had great fun playing in the street.

“The war started when I was a wee boy, but it didn’t really affect me, apart from the fact I used to get a little bit worried about my dad, because he was a chief petty officer in the Navy – but he got home safely.

“He worked as a ship’s carpenter at Hall, Russell & Co in Aberdeen and played centre-forward for his work’s junior football team as well as Banks o’Dee.

“I started out as a striker as well, but I was persuaded to have a shot in goal and it became pretty clear I had some ability in that position. As we moved into the 1950s, I got a bit of attention and good things began happening.”

These included a call-up to the Scotland schoolboy ranks and an outing against their England counterparts at Filbert Street in Leicester. There was plenty of interest from scouts, but while others procrastinated, Burnley stepped in with an offer and Blacklaw joined their ground staff in 1954, even though he later admitted he had no idea where he was going.

What was clear, though, was his desire to find a club which would allow him an element of job security and he had no interest in staying in the juniors.

Building a wall was no problem

As he told the P&J’s Dave Edwards: “I played schoolboy football for Aberdeen, but realised I would probably have to move away to get a chance of a professional career. I came from a working-class family and we weren’t well off. Aberdeen wasn’t prosperous and this was well before the oil boom.

“It still seemed a long way to Burnley and I didn’t even know where it was. But they treated me great. In these days, when you were an apprentice footballer, you were exactly that: an apprentice tradesman who also played football. The club put me through my apprenticeship as a bricklayer”.

He had to be patient for an opening. Burnley’s England goalkeeper Colin McDonald had the gloves and was in no mood to relinquish them.

But, while Blacklaw was forced to wait for two years until his clubmate suffered an injury, he showed his potential on his debut in 1956 during a 6-2 trouncing of Cardiff City at a fogbound Turf Moor just before Christmas.

There was further frustration when McDonald returned and his consistent brilliance meant the Scot was once again left on the periphery. But he was persistent, he kept toiling away behind the scenes and, finally, these qualities paid off when he seized the No 1 spot and clung onto it for the next six years.

And he did so as Burnley produced a fantastic title-winning campaign.

It was a tense season for the team and their manager Harry Potts, but although they were playing catch-up until the final day, they secured a thrilling Championship success – only the second in their history – with a dramatic 2-1 win at Manchester City and the Clarets painted the town red.

In the aftermath, the scale of their achievement became clear. Only two players – Alex Elder and Jimmy McIlroy – had cost a transfer fee, while the others had been recruited from the club’s flourishing youth academy.

With 80,000 inhabitants, the town of Burnley was one of the smallest to have hosted an English first-tier champion, but Blacklaw wasn’t surprised at how they had swept all before them. “We were experienced, we had grown up together and there was a camaraderie and community spirit about the place.

“Harry Potts was a really good manager and he made sure we always knew 100% what we were doing and he worked out our opponents’ weaknesses. We had to fight hard to get in front of Spurs and Wolves, but we did it. It was one of the most momentous things which ever happened to me.”

Blacklaw, who amassed 383 appearances at Burnley, missed just two matches during that heady period, one because he was on international duty with Scotland, the other when Potts controversially rested the whole First XI in preparation for a European game in Hamburg the following week.

He was a fans’ favourite and excelled in so many different contests, defying Everton with a spectacular display in September 1959, Reims with similar pyrotechnics in 1960 and Sheffield Wednesday in the FA Cup in 1961.

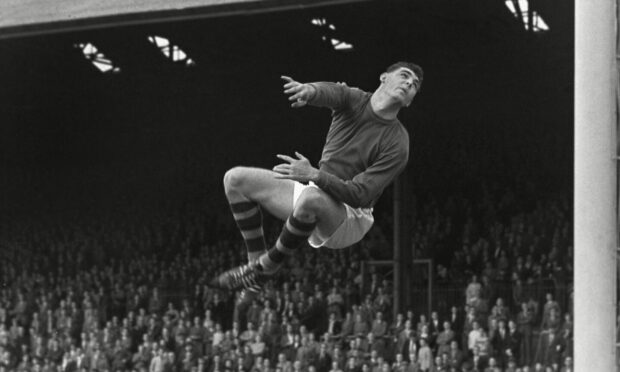

He was acrobatic, uncompromising, a towering presence in his box and consistently capable of shutting down rivals at close quarters. No wonder the Burnley faithful cherished him. And he was involved in another wonderful performance when Scotland travelled to the Bernabeu Stadium in March 1963 for one of the most inspirational occasions of their lives.

The Scots had turned up in Madrid with no great expectations against many of the players who were crowned European champions only 12 months later.

And yet, as Ian Ure recalled: “We played a makeshift team in Spain that night, and yet look at the players we fielded: Billy McNeill, Jim Baxter, Willie Henderson, Denis Law, Ian St John, Davie Wilson and the rest.

“Spain took the lead early on and I can remember Billy McNeill and I both scrambling to retrieve the ball from the back of our net and saying: ‘Jesus, this is going to be some night.’ We thought we were in for a hiding. But then we equalised, and got another, and another, and we went in 4-2 up at half-time.

“We popped in two more for good measure. The Spanish crowd didn’t like it one bit. Stuff was being thrown on to the pitch.”

Blacklaw was more succinct 30 years later when he said: “Nobody expected it, but every time we attacked, we tore them to shreds. I was watching it and rubbing my eyes in disbelief. This was the stuff of dreams.”

However, another foreign trip almost turned into a nightmare.

Blacklaw was no shrinking violet when it came to protecting his teammates. But this led him into trouble when he was held at gunpoint by an Italian policeman in Italy in 1967 after Burnley had eliminated a star-studded Napoli line-line from the European Fairs Cup.

It was a tremendous result for the visitors, but it sparked angry scenes at the end. As Blacklaw recalled: “I was reserve goalkeeper that night, but my replacement Harry Thomson had a great game, pulling off save after save.

“At the end, when he went to shake hands with Alberto Orlando, the Italian spat in his face and threw a punch at him. That was enough for me and I leapt to Harry’s aid, only to be set upon by about half a dozen Italian players and stadium staff who meant business.

“I was a big fella, I could handle myself, and I had been a boxer in my younger days in Aberdeen. As I was getting up off the ground, I was able to throw one guy over my shoulder and down a flight of steps.

“But when I saw a policeman with a gun approaching me, I decided to head for the safety of our dressing room and join the rest of the team.

“It was a very volatile situation. We were later escorted to the airport by an armoured lorry and nine military jeeps.”

Blacklaw eventually moved on to Blackburn Rovers and Blackpool at the end of his career from 1967 to 1970, but there was only one club etched in his heart – and the feeling was reciprocated.

When he died in 2010 at the age of 72, the Burnley players wore black armbands to commemorate him during their match against Arsenal.

More like this: