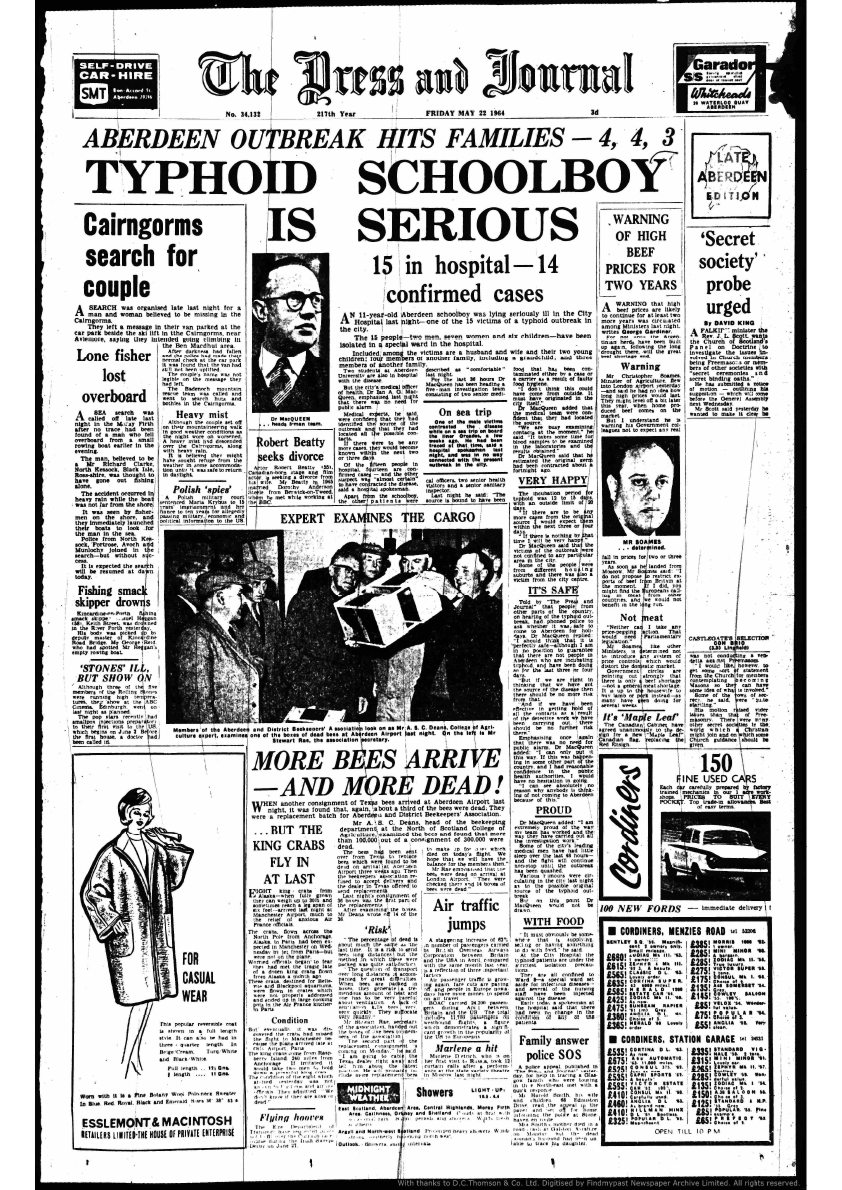

People of a certain age in Aberdeen have never forgotten the great typhoid epidemic which locked down the city in 1964.

Schools were closed, the swings in parks were chained up, more than 500 people of all ages had to be quarantined in hospital, and a 16-year-old Sheena Blackhall was among those who was so fearful she would die from the disease that she told the medics: “Dinna cremate me! I want to be buried!”

The City Hospital was gradually overrun with typhoid patients which led to other medical facilities opening up their beds to a flood of new admissions.

And although an inquiry subsequently discovered that a large can of Argentinean corned beef was to blame for the outbreak, the incident left indelible memories for many of the youngsters caught in its grip.

When the Covid-19 pandemic brought the planet to a standstill in the early part of 2020, it reminded some residents of how swiftly the rug can be pulled from under their feet. And it also cast their minds back to that period in 1964 when the Granite City was isolated from the rest of the world.

Local artist Kate Steenhauer talked remotely to some of her close colleagues and as the likes of Diana Buchan, Ruby Stephen and Pat Robertson chatted about their reminiscences, the seed of an idea was planted in her mind.

As she said: “During the lockdown summer, one of my neighbours told me about the typhoid outbreak in Aberdeen. I have been living in the city for 16 years, but I had never come across that before.

“So when she explained what happened, I thought it would be nice to capture my Aberdonian born-and-bred neighbours’ perspectives from that time and compare it to the situation which we found ourselves in with Covid-19.

“So we ended up having a socially-distanced coffee morning in one of our gardens. In the film, while my neighbours are telling their story, their portraits are drawn live, slowly revealing their faces.

The project has grown in scale since that first meeting.

And, perhaps unsurprisingly, given her first-hand experience of typhoid, writer Sheena Blackhall has joined forces with Kate, composer Mario Sappho, sound mixer Annabel Strange and videographers Alex Cormack and Martina Camatta.

The 25-minute film has been lovingly prepared by the team and it will be screened at Aberdeen University later this week.

But Kate has offered us a preview of this unique collaborative venture.

As the women talk, there is a breathless quality to their evocative memories of what happened nearly 60 years ago because of one rogue tin of beef.

Indeed, they end up almost completing each other’s sentences as their conversation continues with many Doric words dropped into the mix.

One passage runs this: “So there was no boats, no trains, it was like a ghost town. The army was stationed all the way round Aberdeen.

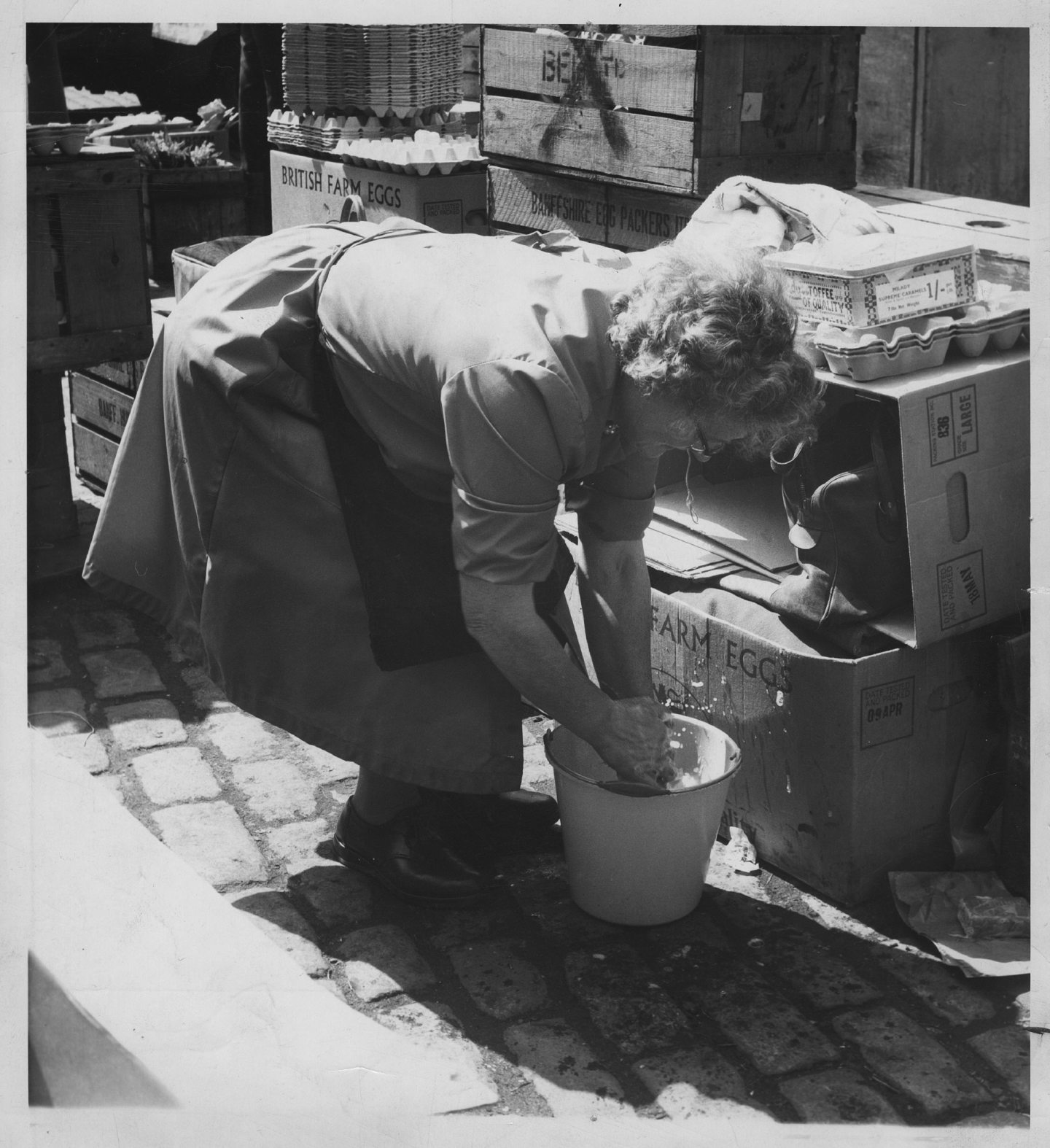

“Aye, you couldna leave Aberdeen, you couldna get into Aberdeen. Lorries had to drive through pads and they were aw sprayed with disinfectant before they left, underside and everything, and were done the same coming back.

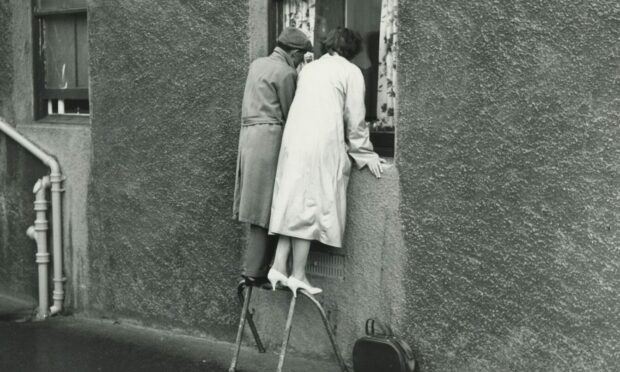

“The schools were closed for weeks and we weren’t allowed oot the house. My maw caught me once, leaning out of the back bedroom windae, on the second floor to see if I could reach the drainpipe, just to get oot, and my maw said to me: ‘And what do you think you’re daeing, young lady!”

Unsurprisingly, these experiences partly steeled these Aberdonians for the Covid lockdown which was announced on March 20 2020, and pulled the curtain down on myriad different activities and communal gatherings.

The women were unprepared for how long the restrictions would remain in place, but contrasted it with what had occurred back in 1964.

‘You did as ye were told at the time’

As they recalled: “What they are on about now is your mental health.

“It’s big notice now… but I cannae understand folks saying: ‘Oh, my mental health’. There was nothin of that and all ye had was your toys, your books and your jigsaw puzzle. In these days, ye were told ‘stay inside’ and that was it.

“If people hadn’t followed that advice and done what they were told, it would have spread like wildfire. And things improved eventually. But it was a long time before ye saw corned beef in the shops again in Aberdeen.”

Sheena told me how much she had enjoyed being involved in the film-making and provided a good reason why many regard her as the “Queen of Doric”.

She said: “I ‘linked’ a puckle o the interviews wi Doric couplets, an helped wi editin the interviews. Doric is ma fist leid [first language], sae I could follae the recordins easy.

“Nae o us fa lived throw the typhoid epidemic will iver forget it. An early TV Time Team filmed a hale episode aboot it…I suggestit they linked it wi Aiberdeen in the plague era, an they did.

“There wir mony similarities, apairt frae the daith rate.”

Sheena was equally articulate at describing her typhoid trauma in English while being confined to hospital after being diagnosed with the disease.

As she recalled in her autobiography: “For the first time, I experienced a kind of panic, a fear of incarceration that was claustrophobic in its intensity, an awful confined crushing sense of restraint.

“I wanted out and I wanted out straight away. Other patients, well enough to walk, crawled around each other like drugged locusts, eyes swollen with sleepless nights, strangers forced together by disease.

“At night, the moan and sob of the sick, delirious women rose and fell in the ward like the eerie wind in a dark tunnel, the tight-locked windows yielding neither the sun nor rain.

“The longer that I stayed in the ward, the less I resisted captivity. I slept, I ate, I slept and every waking moment was planned. Soon, it was the world beyond the glass that was unreal. It took a long, long time to build up the strength.”

Sheena spoke about the quarantine which was implemented during the typhoid epidemic in Aberdeen and highlighted the dangers of ignoring government advice by saying: “It puts a tremendous strain on people.

“One of them was a minister’s daughter. We were being treated with massive doses of penicillin, antibiotic penicillin. Whilst some of us were taking a placebo, she had a massive reaction against the drugs.

“Folk came from London to see what had happened to her, she couldn’t stand, she had blankets over her and they put a cage over the top of the bed.

“People were suited up on the ward like you see on the TV now with the coronavirus. As for the nurses, I have to take my hat off to them, they just carried on and, though it must have been quite scary, they did a grand job.”

With hindsight, it’s remarkable only three deaths were recorded during the oubreak, given how many people were affected. But Sheena was among those who was clapping for carers long before Covid became a part of all our lives.

Tatties and Typhoid Ham is being screened at the Regent Lecture Theatre at Aberdeen University on Friday July 8 at 5.15pm.

Free tickets can be booked at Ticketsource.

Conversation