He was the best-selling Scottish author who grew up in the north of Scotland and spoke Gaelic as his first language.

And, during his early life in Daviot, Alistair MacLean walked to school with his brothers barefoot in the spring and summer to save on the price of shoes.

In another time, the youngster might never have left his roots, witnessed first-hand the devastation and slaughter of the Second World War and taken part in military action from the Arctic to the Aegean and the Indian Ocean, where he was involved in operations against the Japanese in Malaya and Burma.

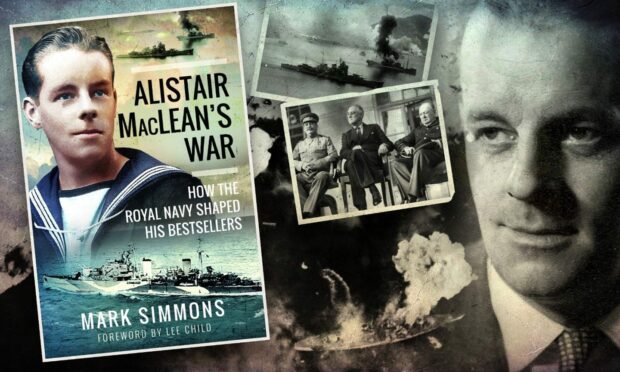

Books by Alistair MacLean stand the test of time

But MacLean’s life changed forever after he was called up by the Royal Navy in 1941 when he was still a teenager, and ventured into the theatre of conflict.

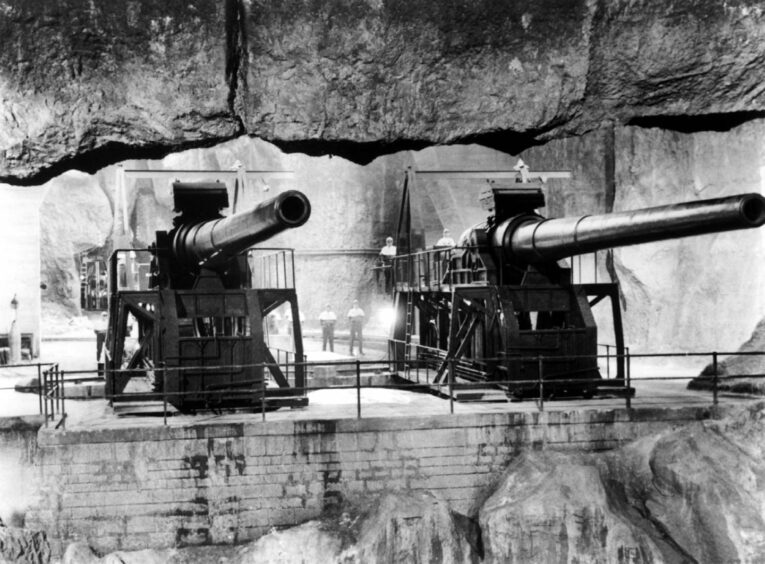

His memories of these different campaigns, allied to his ability to convey them with an action-packed literary flourish – “I’m not a novelist, I’m a storyteller” – subsequently led to him creating such famous works as HMS Ulysses, The Guns of Navarone, Where Eagles Dare and Ice Station Zebra.

And now, a new book has investigated how his recollections of his war service were the catalyst for international book sales of more than 150 million copies.

MacLean, a phlegmatic character who never thrust himself centre stage – even his literary career only began when he entered and won a newspaper story competition – was still in his early 20s when he joined the Arctic convoys on what were some of the most dangerous journeys during the war.

And, even as he was engaged in crucial missions on HMS Royalist to provide sorely-needed supplies to beleaguered Soviet citizens, these often had tragic consequences for many of his colleagues as they battled German resistance.

These sailors did vital war work

Author Mark Simmons explained: “The convoys took a million tons of supplies to the Soviet Union, including 5,000 tanks and 7,000 aircraft. The Royal Navy lost 18 warships and 1,994 men in the years 1941-45 while 98 merchant ships were lost with 829 men.

“Yet it was not until 2012 that a campaign medal, the Arctic Star, was awarded retrospectively after much lobbying, for service in the convoys.”

By that stage, of course, most of the old warriors were dead.

He spoke about these convoys as “missions which pushed men to the limits of their endurance” and “where everybody lived in fear on a constant basis. If you landed in the water, you were lucky to survive for five minutes”.

As the war progressed, he and the Royalist moved to the Mediterranean, as part of the invasion of southern France, helping to sink blockade runners which were operating off Crete and bombarding Milos in the Aegean Sea.

But when the ship returned to Portsmouth, Charlie Dunbar from Banff joined the crew for his first taste of life aboard a fighting vessel and, despite being apprehensive and wishing he was back in Scotland, quickly struck up a friendship with his compatriot, the now-battle-hardened MacLean.

Dunbar recalled: “This fellow heard me speaking in a Scottish accent, so he came over and asked where I was from and I told him I was Charlie Dunbar, the cinema projectionist at the Playhouse in Keith.

“Well, he smiled and said he was Alistair MacLean from the same north and north-east part of Scotland. It was a relief to find out I was no longer on my own and, thereafter, he looked after me and asked how I was settling in.”

In 1945, in the Far East theatre, the pair saw action while escorting carrier groups in operations against targets in Burma, Malaya, and Sumatra. And, after the Japanese surrender on August 15 1945, HMS Royalist helped evacuate liberated POWs from the horrors of Changi prison in Singapore.

MacLean and his comrades were present for Lord Mountbatten’s ceremony of official surrender and noticed Japanese soldiers being forced to clean the parade ground, to the point of picking grass between the cobblestones.

He highlighted how Indian soldiers, who were incensed at what had happened to Allied troops in the prison camps, stood over them with bayonets, prodding them or kicking their backsides as an outlet for their rage.

Too many perished in the Far East

He talked about his compassion for these “poor lads, thin as rakes, with their ribs protruding through their skin” and expressed his belief that those who fought in Japan were every bit as important as their counterparts in Europe.

And he added: “Many of these boys had never even heard of places like Singapore and Burma. But they went there and too many never came home.”

MacLean was not a prolific writer at that stage, but perserverance paid dividends for those who believed there was an audience for his vivid depictions of the convoys, so memorably captured in a full-length book.

As Simmonds has written: “Few first novels have had the impact of Alistair MacLean’s HMS Ulysses, published by Collins in 1955.

“The book remarkably sold a quarter of a million copies in hardback in the first six months, a record at the time. It was after winning first prize, £100 [in the Glasgow Herald competition] that MacLean came to attention of Ian Chapman, who worked for the publishers in their Glasgow office.

“After some gentle persuasion and the offer of an advance of £1,000, Chapman, who would become a lifelong friend to Alistair, managed to convince the reluctant author to write a novel. It was hardly surprising that he turned to his own wartime experiences in the Royal Navy.”

Even today, almost 70 years later, HMS Ulysses has the cold smack of the frozen sea, the frisson of anticipation and dread among the characters and powerfully evocative descriptions of the hazards these men faced. There’s no padding, no redundant romantic interest, nothing extraneous at all.

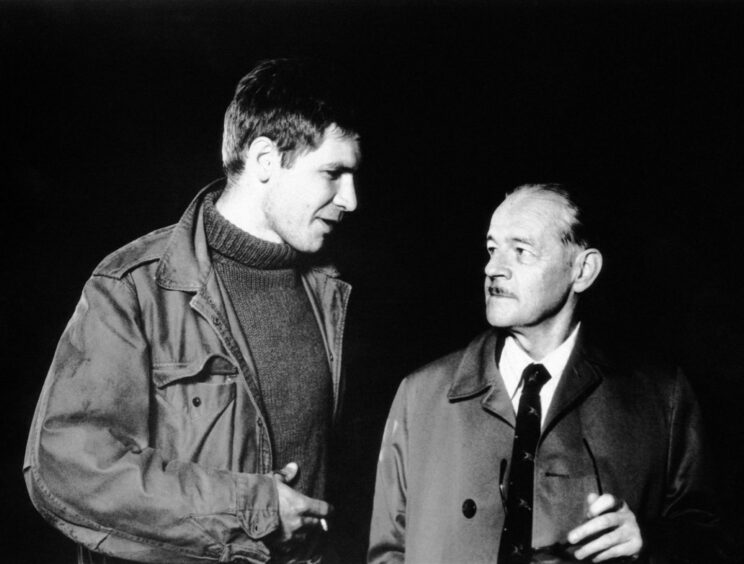

As Ian Rankin said about Where Eagles Dare: “It’s probably the first grown-up book I read. I’d have been about 11 and it may have belonged to my dad.

“It’s real Boys Own stuff and none the worse for that. I stumbled across a copy in a second-hand bookshop a couple of years ago and so I got the chance to re-read it. It’s great stuff.”

Simmons’ intriguing new work comes with its own glossary and acronyms, ranging from AIO to GRU, LTO to MGB and RAMC to SOE.

This list also includes, amusingly for Scottish readers, the words “Manse” and “Mod”, the latter defining the Gaelic festival of music, arts and culture.

But it’s a reminder that, however exotic or far-flung MacLean’s plots may have been, he never forgot the early days when he was growing up near Inverness.

He died in 1987, aged just 64, and ended up being buried in the same cemetery in Switzerland as Where Eagles Dare star Richard Burton.

North-east journalist, Jack Webster, who penned an acclaimed biography of MacLean, travelled to the burial site of these two talented, temperamental and occasionally tempestuous figures with the author’s first wife Gisela.

He said: “We wandered along to the cemetery, an unpretentious little place where the first grave on the left might well have belonged to a local labourer, except for the fact that the headstone told a different story: Richard Burton.

Gone but never ever forgotten

“Across the narrow pathway, just a few yards away, we came upon that other stone, marking the last resting place of the warm, wayward, fallible human being: Alistair MacLean.

“And there they lie in peace forever, near a waterfall which tumbles down a little ravine like a sparkling Highland burn.”

In death, as in life, there is always a compelling story with this fellow! And the seeds were sown as he was serving the Allied cause.

Alistair MacLean’s War by Mark Simmons is published by Pen & Sword.

Conversation