A new book for Highland railway lovers leaves no points, sleeper or wrong kind of leaf unturned to discover the glories and quirks of the network’s buildings, from the most fancy to the most humble.

Its author, Neil Sinclair has been absorbing all things railway from a very young age, when his father would reminisce over the building of the Aviemore line.

The line was built through his grandfather’s land at the end of the 19th century.

Neil started taking photographs of railways from 1958, aged 14.

His passion grew from there during rail journeys to and from Rannoch School in Perthshire, and holidays on the family farm in Inverness-shire.

He’s been writing about Highland railways since 1969, including a definitive insight into the Highland Main Line in 1998; and since 1976 has been behind the many editions of the Strathspey Railway Guide book, which he’s currently updating.

His latest release, Highland Railway Buildings (Lightmoor Press/ Highland Railway Society), whilst surgical in its detail, chugs along engagingly, as Neil has filleted the story into an easy journey with many stops of interest.

First he sets out the context and history of the north railways from their early days in Inverness and Perth and how they branched to points north, east and west.

He then lets chronology take over, covering the periods 1875-1889; the 1890s and the twentieth century.

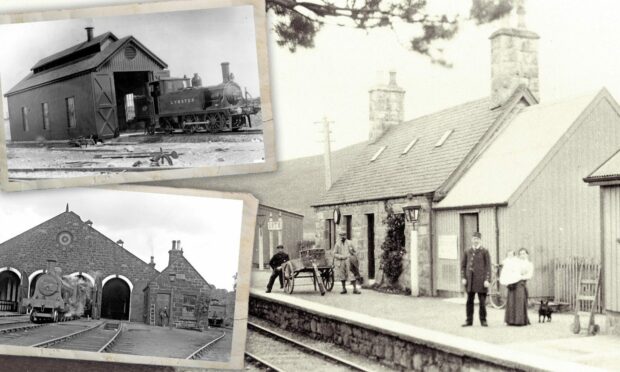

The lavish illustrations —300 of them— make the decades disappear, a real sentimental journey for those who remember, not that long ago, uniformed staff and ticket offices at every station, luggage carts, colonnades and waiting rooms.

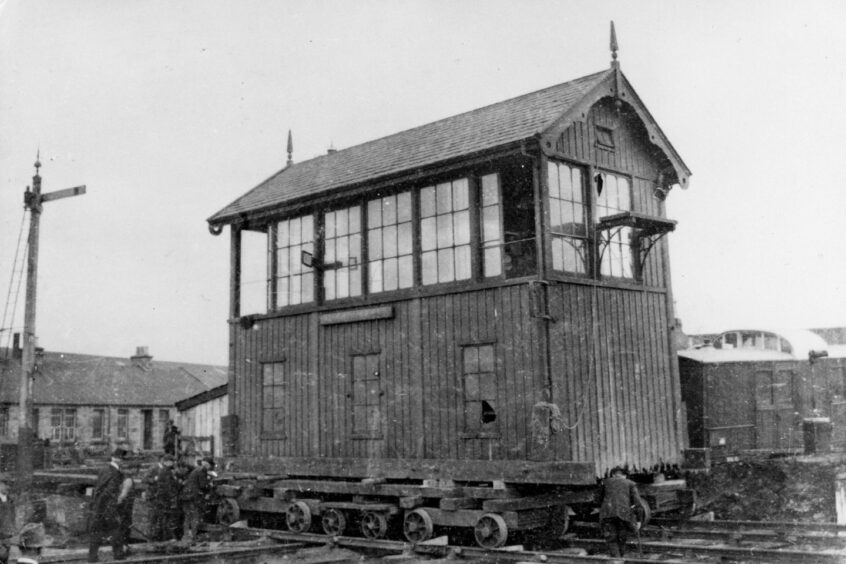

Platelayers’ huts, linesman’s huts, signal boxes, shelters, sheds of all sizes, stationmaster’s houses, railway workers cottages, private waiting rooms for aristocracy, grand hotels — nothing in the development of the Highland railway escapes Neil’s meticulous attention.

He said: “The importance of the architecture of the railway isn’t really acknowledged, or remembered today.

“Often the station was the main building in the locality, from Perthshire to Caithness.

“They were a major part of the architecture of the area alongside only churches and banks.

“In some rural areas they were the largest building in the area.”

Neil says one of the book’s important functions is to identify who the architects of the stations were, including the hitherto unsung George Craig, the Edinburgh architect who designed the grand state schools of Leith in the 1880s.

He held the post of architect in the Highland Railway’s engineering department from the late 1870s.

Neil said: “Normally stations were attributed to the civil engineer, which was fair enough, they built the railways, they were in charge and would have specified what kind and size of station.

“But George Craig started with Beauly station and his designs were used for 25 years for quite distinctive stations.

“He incorporated a lot of decorative detail like the crow-stepped gables and the finials.”

Pitlochry, Nairn, Dingwall and Grantown-on-Spey are examples of Craig-designed stations.

Fresh eyes

Neil hopes his book will encourage travellers to look at the constructions around the Highland railway with fresh eyes.

There are quite marked differences in materials, from wood to stone, concrete and brick.

“Helmsdale station is unusual, especially for its time, in being built out of concrete.

“The Mound station is built using brick from the Duke of Sutherland’s Brora brick works.

Landowners’ influence

“Often the kind of station you got depended on if you had a wealthy landowner.

“They would often insist on having their own waiting rooms in exchange for a stop on their estate.

“But also Highland Railway’s funds, or lack of them at the time, dictated the choice of materials and style.”

Locally made infrastructure

It’s not only the stations which are worth a look, but their supporting infrastructure.

Neil said: “For example, note the distinctive iron footbridges, quite a few of which were made in the Rose Street foundry in Inverness.

“Highland Railway tried harder than most to use local workers and contractors.

“Look at the houses too, sitting in groups near the stations, with the stationmaster’s house bigger than the others, with a porch, and the smaller railway workers’ cottages, built like farmworkers’ cottages.”

Inverness station falls short

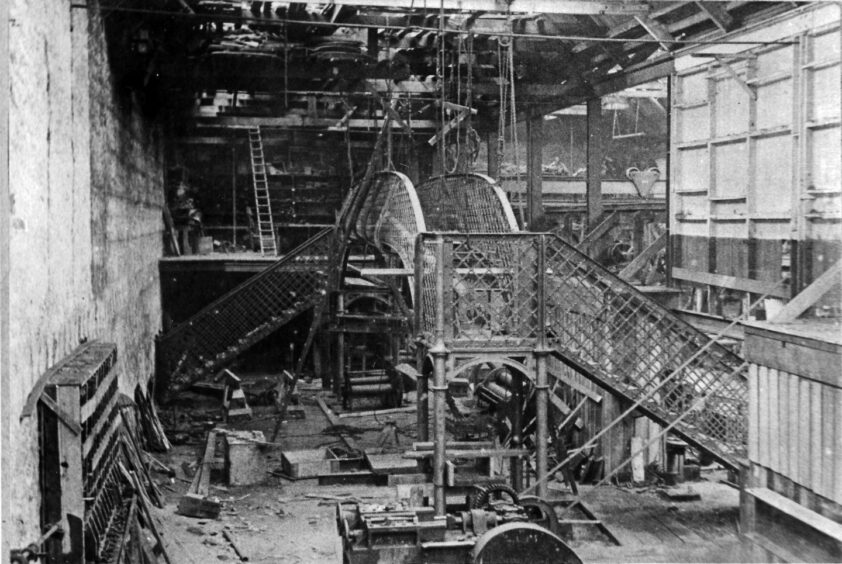

Inverness station, with its long lost round house engine shed, lacks the grandeur you might expect from such an important hub, Neil admits.

“It’s quite plain. The lack of canopies above the platform is disappointing for passengers disembarking into the rain,” he said.

There were proposals for its improvement in the 1890s, but in the end the money man, Highland Railway chairman William Whitelaw decided investment should go into developing big hotels, like Dornoch and Strathpeffer.

Neil said: “His thought was to get people travelling over the railway to get to the hotels, and they should be quite profitable.

“Strathpeffer wasn’t though, being built in the style of continental spa towns, only for spas to go out of fashion after the first World War.”

Optimism

Is the legacy of beautiful Highland railway buildings at risk from trends to build ‘bus shelter’ type railway stops?

Neil thinks not.

He said: “Fortunately the era of demolishing buildings and putting up ‘bus shelters’ has come to an end, partly because you can sell stone-built properties for housing or commerce.

“Highland Railway built more houses than stations, more houses than any other British railway company because some of the locations were so remote that they had to provide housing.

“The early little wooden buildings have tended not to survive, but I’m confident that the stone-built ones will survive and be looked after for years to come.”

You might enjoy:

Railway enthusiast’s love letter to classic Perth-Inverness diesel trains

Do you remember the Callander to Oban Line?

Conversation