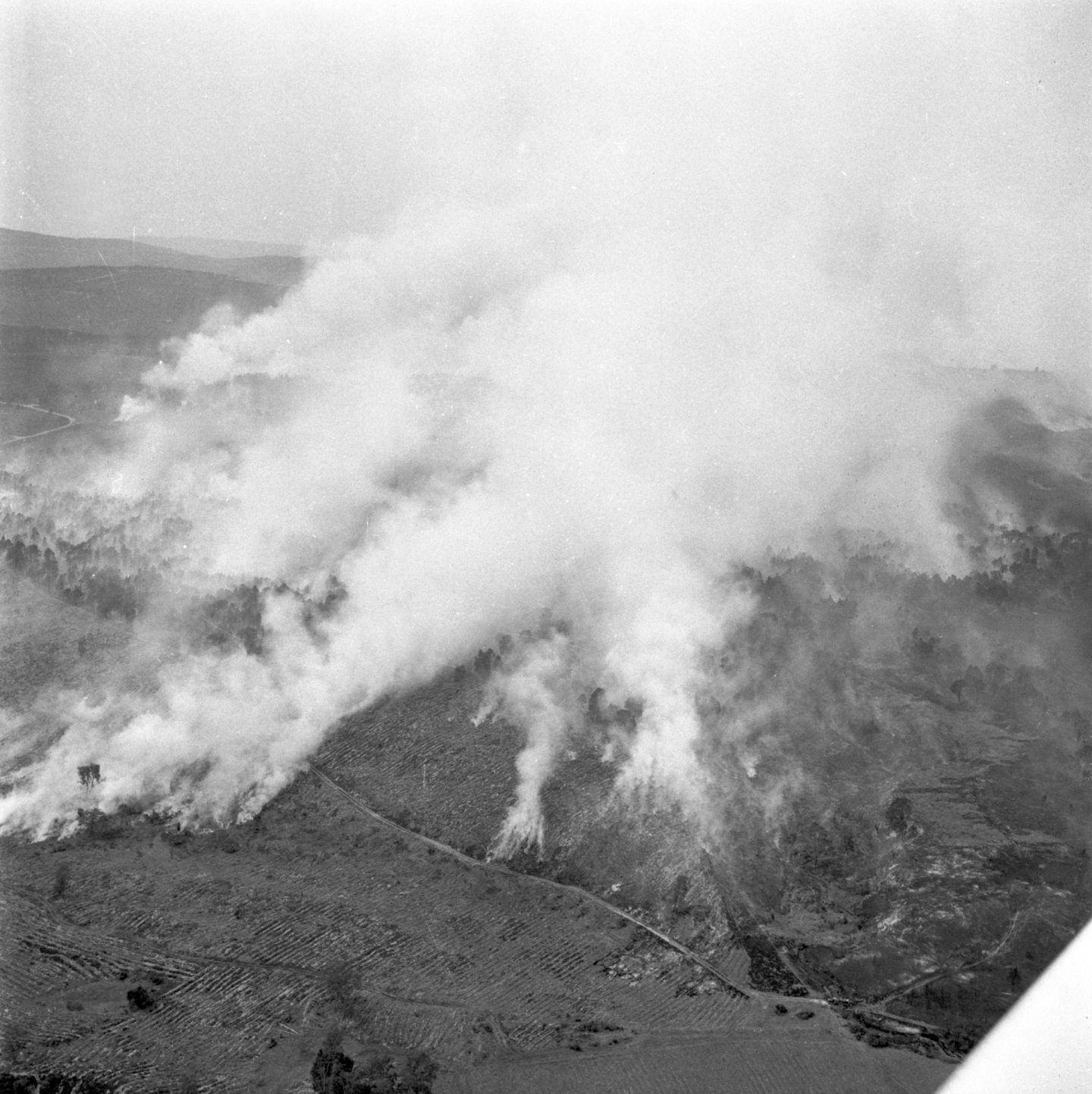

As weeks passed without rain across the north-east in the summer of 1976, parts of the region began to experience a strange phenomenon.

With water rationing and hosepipe bans in place in Aberdeen, Inverness and Lossiemouth and extending all the way across Banff and Buchan, the parched earth led to the emergence of those who thought they could use their powers to discover untapped sources of precious liquid under the ground.

Divining – or dowsing – is widely regarded as a pseudoscience, a practice best left to the likes of Mulder and Scully to investigate in an X Files episode – possibly entitled “The Drouth is Out There” – but it was taken seriously enough during the months-long drought that Press & Journal feature writer, Jim Hunter, was sent to talk to one of the people who was a genuine believer.

And James Chapman, a 74-year-old Buchan farmer, offered several compelling reasons to at least ponder the theory for a few minutes.

‘You either have the gift or you don’t’

Mr Hunter, who is now a renowned historian and professor emeritus at the University of Highlands and Islands – and a P&J columnist – approached the subject with an open mind and allowed him to tell his story.

As Mr Chapman said: “I’ve been busier this last year or two than ever before. Partly because of the drought. Partly because of all the new houses [which were being constructed in the area].

“Just after I left school, I was working on this farm where the farmer’s son was a diviner. And that’s how I found out I had the thing as well.”

The “thing” was a talent for unearthing seams of water in the unlikeliest of places. But could it be that this special gift ran in the family?

Anything was worthwhile in a drought

He said: “No, it doesn’t seem to have anything to do with that. My father was a blacksmith at Fyvie – but no, he was no diviner.

“My oldest daughter’s lassie – she has it right enough. But she is the only diviner in the family apart from myself.”

To be fair, he wasn’t profiting from his knowledge, nor was he trying to argue that he was special. If it was all in his mind, it was an innocent fixation.

His results were pretty impressive

As Mr Hunter wrote: “He does not claim to know why or how divining works, though he reckons it has something to do with electricity.

“But it certainly produces results – as is testified to by the hundreds of wells he has discovered in an expanse of territory, stretching, as he puts it himself ‘from Insch to Fraserburgh’.

“Has he had any failures? Well, he doesn’t claim to know the depth of water sources. So he can always say the water is there – just too far down to reach.

“And he has completely convinced more than one sceptic simply by finding water where none could previously be located. And, as wells have dried up over the last couple of months, he has been continuously in demand.”

Rain had arrived in Banff and Buchan and elsewhere in Scotland by the time Mr Hunter met his compatriot. But the earth was still bone dry and many of the hosepipe restrictions were extended for several months into the autumn.

So it was time to challenge the diviner. And this was what happened.

“Mr Chapman produces his equipment. Not the forked hazel stick I had expected, but a two-foot strip of highly flexible steel – the mainspring of a gramophone. Wood, he explains, works alright, but tends to snap.

Two men, two different outcomes

“What James Chapman refers to as ‘water veins’ run north-south across this part of Buchan. And they are, he says, maybe 30 to 35 yards apart.

“We walk slowly across one such ‘vein’. The spring in Mr Chapman’s hands contorts and bends – and almost escapes from his grasp.

“He gives the metal strip to me. I hold it as he directs. We walk back across the ‘vein’. I feel…ABSOLUTELY NOTHING!”

Even now, in 2022, dowsing is still used by some farmers and water engineers in the UK, but many experts have dismissed it as having no basis in science.

Their argument runs along the lines of: “Britain is an island, entirely surrounded by water, so it’s hardly surprising it can be sourced at many different locations and especially in the north and north east of Scotland”.

In short, diviners often achieve good results because random chance offers them a high probability of finding water in favourable terrain.

But where’s the fun in that? Where’s The Diviner Comedy?

And here’s Jim Hunter’s own story

We caught up with Mr Hunter this week to find out whether he believed there was anything to the claims made by dowsers – and he told us quite a tale.

He said: “I am naturally sceptical about these sorts of claims, but I do think there is something in water divining.

“The most persuasive case I know of concerns my late father-in-law. Back in the 1950s, he and my late mother-in-law, previously resident in Aberdeen, bought – for just over £500! – a house in rural Aberdeenshire.

“This had begun life as a home on a croft or a smallholding of some sort. There was a water supply from a well but this was inadequate and uncertain. So my father-in-law called in a water diviner who walked systematically across the garden using the standard hazel forked twig.

This was pretty spooky….

“He pointed to a particular place. ‘There’s plenty water here,’ he said. ‘You’ll reach it at 13 feet down.’

“Next came one of the contractors who specialised in digging wells. Down went the excavation. At 12 feet 6 inches, there was water as predicted.

“The well was lined, the bottom covered in sand by way of filtration and – my father-in-law being a plumber to trade – an electric pumping mechanism installed. This kept a tank in the loft supplied, so water was there whenever it was needed. It never failed even in 1976 and, being tested regularly, always got the highest possible rating.

“So there you are!”