It was the equivalent of HS2 in its day.

The size, scale and impact of the Caledonian Canal when it was being built more than 200 years ago can’t be overstated.

There was grand ambition behind it — opening trade to the world at a time of expanding empire; creating employment; stemming Scottish emigration; enabling the swift passage of Royal Navy ships when Napoleon was at his most threatening; a shortcut for fisheries.

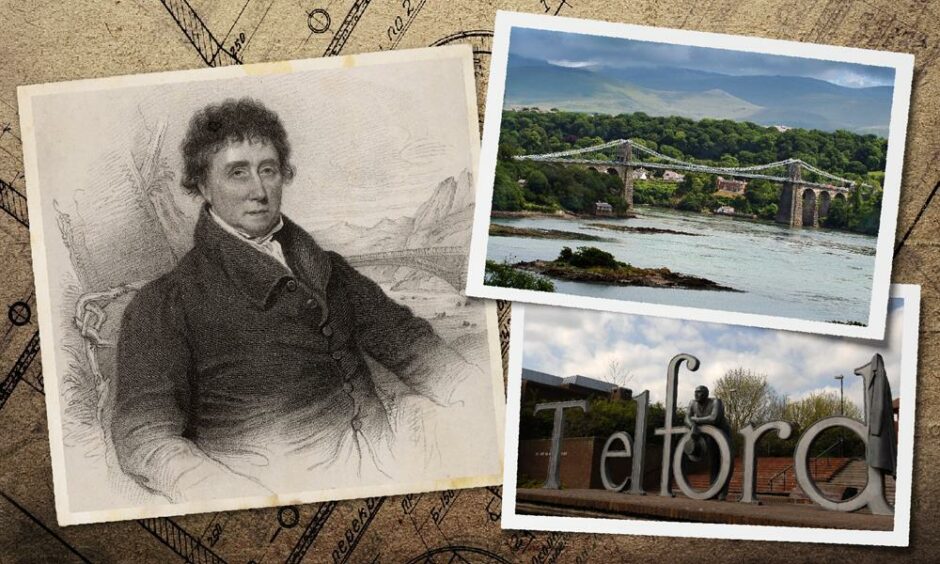

The man behind it was arguably the greatest Victorian civil engineer of this time.

Thomas Telford, who had risen from humble Dumfries-shire origins to become ‘The Colossus of Roads’ and bridges, harbours, churches and of course canals in England, Scotland, Wales and Sweden.

There had been unsuccessful thoughts about trying to build a waterway across Scotland’s Great Glen, linking the Atlantic and the North Sea for at least a couple of centuries, but it was deemed too difficult, impossible even.

Routes for the canal had already been mapped

James Watt had mapped a canal through the Great Glen in 1773, as had John Rennie (1761-1821) from East Lothian, considered the greatest civil engineer of his age.

Thomas Telford (1757-1834) consulted them, along with William Jessop, under whom he built the Ellesmere Canal.

But it was Telford’s particular genius which made the Caledonian Canal work where the others had failed even to get so much as a toe off the starting block.

Scottish Canal’s heritage manager Chris O’ Connell spends his time caring for the heritage and archaeology of Scotland’s canal estate.

His in-depth knowledge of the 66-mile route of the Caledonian Canal gives him a clear perspective on why Telford cracked it where others had failed.

He said: “His genius was to take the existing waterways, the lochs of the Great Glen and connect them with 22 miles of canal.

“You are constrained in where you can build infrastructure in the Great Glen as it’s a steep-sided valley with little room for manoeuvre, but it’s the shortest route across the Highlands.”

Telford won out because of his pragmatism, Chris went on.

“From what I read of him in our archives you get a sense of his can-do attitude.

“If there’s a river in the way we’ll circumnavigate it, or in the case of the River Oich, divert it.

“We’ll straighten out ox-bow bends, let’s get it done.

“His pragmatism was his greatest strength.”

Telford surveyed the route in 1802 and sent a report outlining his findings to Parliament.

Parliament authorises the Caledonian Canal

The government was convinced and passed an Act in 1803 to enable the construction of the Caledonian Canal to begin.

Public funds would be used, unlike in other Scottish canal projects which were owned privately and raised their own money.

It would cost £350,000 (around £33m today) and it would take seven years to build, Telford told Parliament.

Those figures proved wildly inaccurate, and it’s possible Telford knew that.

In fact it took 18 years to build and cost £1.2 million, more than £140 million today.

But it got the government’s seal of approval, and construction began in 1803.

In those days there was no requirement to hold anything up with niceties like public consultations or environmental impact reports.

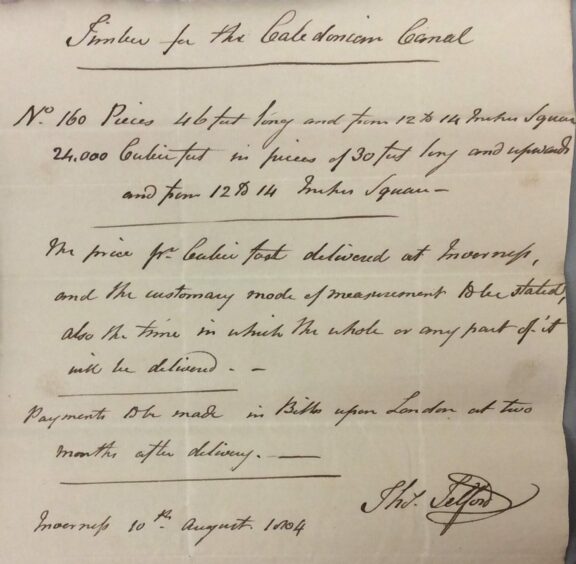

Telford travelled the route, securing agreements from landowners for the use of their land, and materials, like timber and stone, from their estates.

Public in favour

There was not much opposition, the feeling being that a canal should have been attempted a century earlier.

And perhaps it should, as history would reveal later, for when the canal opened in 1822, its pinnacle had effectively passed, as the age of rail took over.

But for now, the project got underway with enthusiasm.

Local labour and contractors were hired to work in circumstances inconceivable in today’s world.

Harder to build than HS2

“The comparison with HS2 is right,” Chris said. “But this was even harder than building HS2.

“They did it all by hand.

“The labourers, although dedicated, had other things to do, they might have to go home to bring in the harvest, tend the cattle, bring in the crops, so unlike the contracted labour force on HS2 you’ve got a fluid workforce reflecting the culture of the time.”

When you visit the canal, take in the magnitude of the stonework.

Chris said: “Sandstone and granite stones, all hewn by masons, all hand-carved, or using two-man mason saws.

“Thomas Telford was an innovator and did use steam engines, and steam dredging materials later, but remember, it’s 1803.

“It was basically ropes, tackle, horses and a lot of burly men.”

Who built the Caledonian Canal?

Sadly there are very few records of who the canal labourers were, which raises questions in Chris’s mind.

“What we don’t know is what women were doing on the canal, we don’t have any records.

“Who was feeding the men? Where were their quarters?

“There’s an under-representation I think in what we know about who and what gender worked on the canal.

“It’s assumed it was men because it’s that kind of burly work, but that’s not necessarily true.”

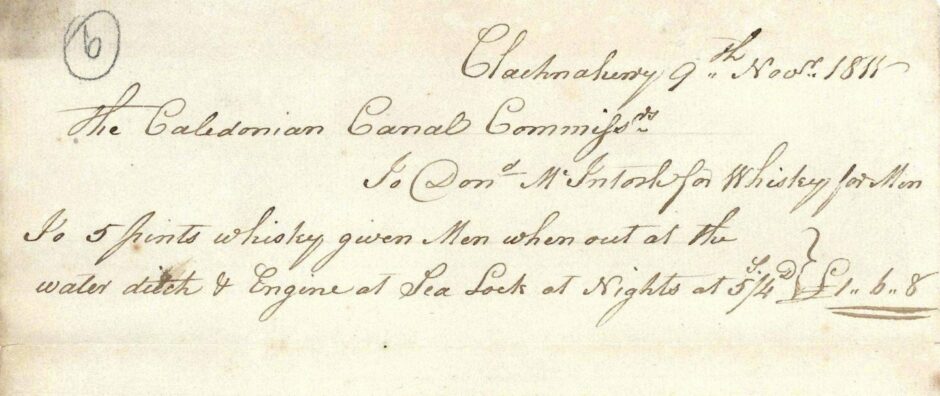

Canal workers paid in whisky

We do know that men working in water were paid a ration of whisky and that one year the bill for that along was 200 guineas.

The government eventually clamped down on this perk.

Can you help name the workmen who built the Caledonian Canal?

The only names available to researchers looking through records for men who worked on the canal are those in the top tier such as the superintendent, the chief engineer.

Chris reckons hundreds of families up and down the canal or further afield will have ancestors who worked on the canal, and would like to hear from them if they have knowledge to share.

He can be contacted at Chris.O’Connell@scottishcanals.co.uk.

The cracks began to show

After a triumphant opening, the cracks soon began to show, in every sense.

By the 1840s problems were already coming to light – finances were in short supply, and repairs were needed after sections collapsed.

Debates were held about the canal’s future.

Should it be rebuilt or should it be closed?

Had it served its purpose and already become irrelevant?

The decision was taken to invest government money in the canal, make repairs and hope for a bounce back in trade and usage – a bounce-back that never really materialised.

Times had changed irrevocably – but the canal had a saviour, as we shall see in part 3 of this series.

With thanks to High Life Highland’s Highland Archive Centre

More like this:

Caledonian Canal 200th anniversary: Much more than just a waterway

Unlocking the key to a celebration of Scotland’s great canal journeys

Thomas Telford: Kind, happy and fun-loving Colossus of Roads

Conversation