Many viewers were enchanted by the adventures of Prunella Scales and Timothy West during their TV series Great Canal Journeys.

It wasn’t just the beauty of the landscape, nor the obvious signs the couple loved each other deeply, even though Pru’s mind was occasionally clouded in the fog of dementia.

But also the way in which their programmes offered a reminder of the engineering skill which lay behind the construction of these waterways across Britain.

They wend and weave their way

In 2016, the acting duo negotiated the Caledonian Canal and spoke admiringly about the genius of the Scottish engineer, Thomas Telford, whose unstinting efforts helped bring the project to fruition exactly 200 years ago.

Mr West, who has died at the age of 90, often talked about his love for the waterways which steered the couple to some of the picturesque villages in the north of Scotland.

And he and his wife were especially delighted by their time on the Crinan Canal, which opened in 1801, and connects the village of Ardrishaig on Loch Gilp with the Sound of Jura, in providing a navigable route between the Clyde and the Inner Hebrides.

It was, in his words: “a treasure trove”. And the series was the same for viewers.

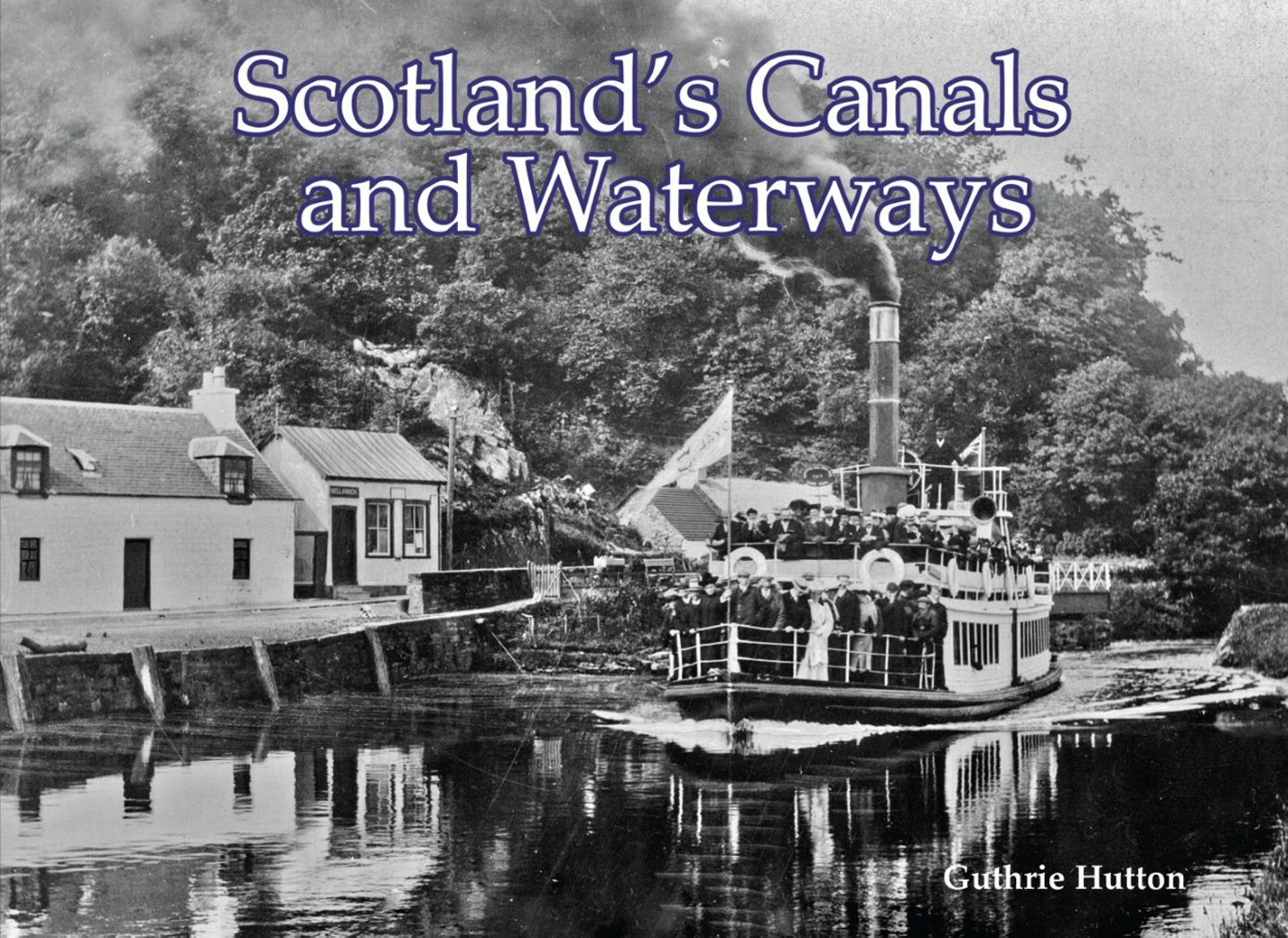

Author Guthrie Hutton shares the actors’ passion for these features of the Scottish countryside, which once teemed with industrial life in the 1800s and 1900s.

‘Almost as if Mother Nature had laid out natural routes’

As a means of connecting coasts on either side of the country, they were the perfect means of stimulating trade and commerce in their heyday.

As he said: “Through the central lowlands, the Great Glen and in mid Argyll, it was almost as if Mother Nature had laid out natural routes.

“Canals have been a big part of my life. I have sailed on them, walked beside them, found solace in their tranquillity and been thrilled by their engineering magnificence.”

The locks and barges are in his DNA. And now, he has written a book about the many diverse canals which have at different stages thrived in Scotland.

Not for the first time, Telford emerges as a towering figure. He revived the faltering fortunes of the Crinan Canal which was in a poor state just a few years after it was built and even faced the prospect of premature closure.

However, cometh the hour and the indefatigable Telford not only rescued it from the axe, but proposed improvements which ensured that it survived and thrived.

It gained royal seal of approval

Indeed, his bold redevelopment plans were sufficiently impressive that, 30 years later, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert sailed along the canal on a horse-drawn barge on a trip which inspired steamer operators David Hutcheson & Co to create the “Royal Route” between the Clyde and Inverness.

It was very popular, but Telford’s sights were set on a larger project and he always had the philosophy that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains.

Which brings us to the Caledonian Canal, the longest, widest and deepest of its type in Scotland; in the west, it has even got the country’s highest mountain, Ben Nevis, as an imposing backdrop to the nearby swing bridge at Banavie, next to the flight of eight locks known as Neptune’s Staircase.

Back-breaking labour for those who toiled on canals in Scotland

Mr Hutton said: “The poet Robert Southey, a friend of Telford, who designed the canal described this lock flight as ‘the greatest work of art in Britain’.

“It may not quite be that, but it is certainly impressive and is seen here [in the picture below] looking down towards Loch Linnhe and Loch Eil.

“Some boats are working through the locks and a team of men are using poles to rotate a capstan which, wound in a chain, connected to the lock gate to either open or close it. [A system later replaced by hydraulic mechanisms].

“Staircase locks such as those at Banavie were built as a single entity with every lock having gates in common with the neighbouring locks.

It was back-breaking work

“They were cheaper to build, but caused operational bottlenecks, because a large boat had to go through the whole flight before another could pass in the opposite direction.”

This was back-breaking labour, particularly at the height of summer or in the depths of winter, but these were redoubtable men who toiled on the canals.

However, there were others who lived and sailed in the lap of luxury during the Victorian age as pleasure cruises arrived in large numbers.

These passenger steamers conveyed well-to-do tourists along the canal as part of the “Royal Route” and operated from a wharf above the top lock.

No expense was spared in making the voyages an unforgettable experience and the public flocked to the north of Scotland to enjoy themselves.

As Mr Hutton highlights: “For people coming from or going on to Crinan, a coach service ran between Corpach and the steamer wharf at Banavie. And later, a spur from the Mallaig railway was built to run up to the wharf.

This was a life of luxury for some

“At the height of operations, two paddle steamers worked the route, Gondolier and Gairlochy. They set off from either Banavie or Inverness, one going north and the other south, and they passed each other roughly halfway along the canal on Loch Oich.

“It was an arragement that came to an abrupt halt on Christmas Eve 1919 when Gairlochy caught fire at Fort Augustus and was burnt to the waterline.”

They couldn’t have known it, but that was an omen of things to come.

As the 20th century progressed, a number of canals across the north and north-east became increasingly superfluous to requirements.

The Aberdeenshire Canal, which opened in 1805 and ran alongside the Don between a terminal close to Aberdeen Harbour, did not survive the construction of the Great North of Scotland Railway between Aberdeen and Huntly.

It was a similar story in Dingwall where the idea of building a canal from the mouth of the River Conon, hugging the shoreline to meet the River Peffrey, led to the construction of a short-lived service, which was replaced by trains.

Mr Hutton said: “Some canals were successful, others less so, but time caught up with them all. Against the odds, most of them remained largely intact up to the mid-20th century, but then faced major challenges.

“The Crinan and Caledonian Canals were still operational, but age and lack of investment had taken their toll and both required major remedial work to make them fit for the future [and this is still an ongoing venture].

The public rose to the occasion

“In the lowlands, canals were seen as old, done, dirty and dangerous. The Forth & Clyde Canals were closed and almost ruined in the 1960s, but within a decade, enthusiasts had joined forces to agitate for their reinstatement.”

Once again, members of the public had decided some heritage was worth protecting, even if it needed volunteers to battle against official neglect.

There is at least hope, not just because of the renewed interest in barges, sparked by the likes of Prunella and Timothy.

And Huntly singer Iona Fyfe, who appeared on one of the early canal programmes and is currently standing to become rector at Aberdeen University, recalled the loving fashion in which the duo welcomed her to their world.

It was incredibly heartwarming

She told the P&J: I must have been 18 years old. They invited me out to Tarbet, and asked me to sing the Crinin Canal song. I was a little nervous but everyone was so kind.

“Everyone stayed on the barge overnight. The crew, as well as Tim and Pru invited me to stay over, but I had to get back to Glasgow for classes [at the Scottish Conservatoire].

“Tim and Pru were so kind and warm, but what was most heartwarming was the way he was with Pru. This was one of the first seasons that they filmed after Pru had been diagnosed with vascular dementia in 2014.

“He was so kind, so patient and so loving towards Pru. You could tell they had been married for more than 50 years.”

He will be missed. As will the heyday of these wonderful canal barges.

Conversation