The Caledonian Canal was opened 200 years ago this year, and the P&J is celebrating.

Celebrating because it’s so much more than ‘just’ a canal.

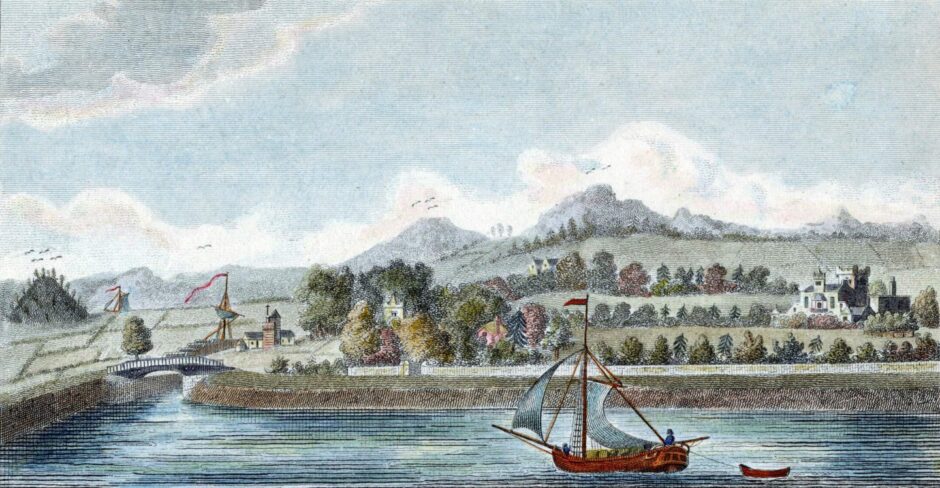

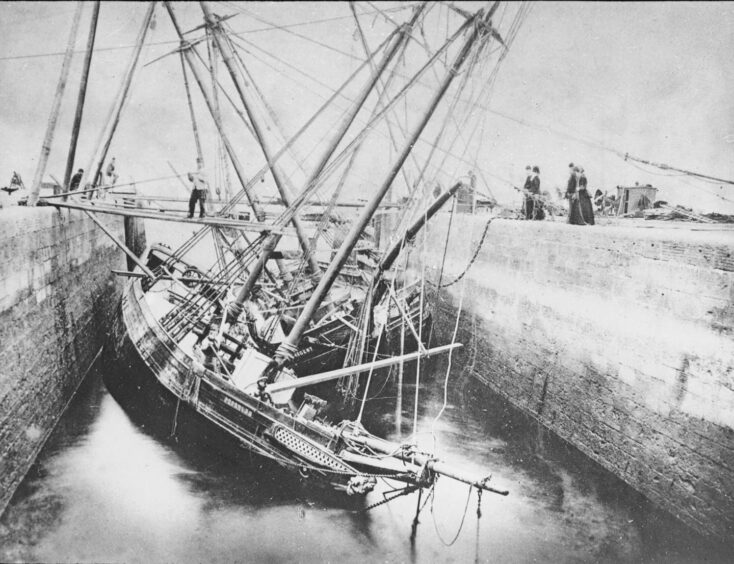

It opened up a waterway from the Atlantic to the North Sea, saving ships from a perilous journey round Scotland’s north coast.

That’s very helpful — but again, it was much more than a lifesaver for trading ships.

The Caledonian Canal was the catalyst for massive growth, progress and change in the Highland, and that’s an understatement.

In some parts of the far north-west, they didn’t even have the wheel.

You read that right. It seems incredible.

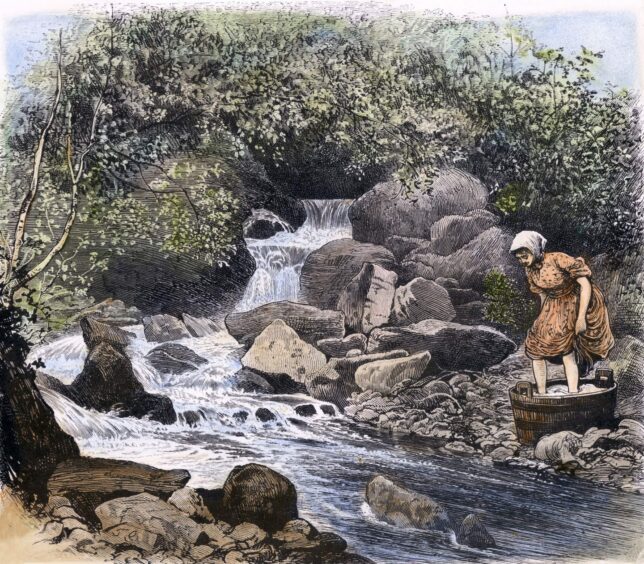

Goods were hauled around on sleds pulled by people, or maybe ponies if lucky.

The Highlands were draining people in their thousands.

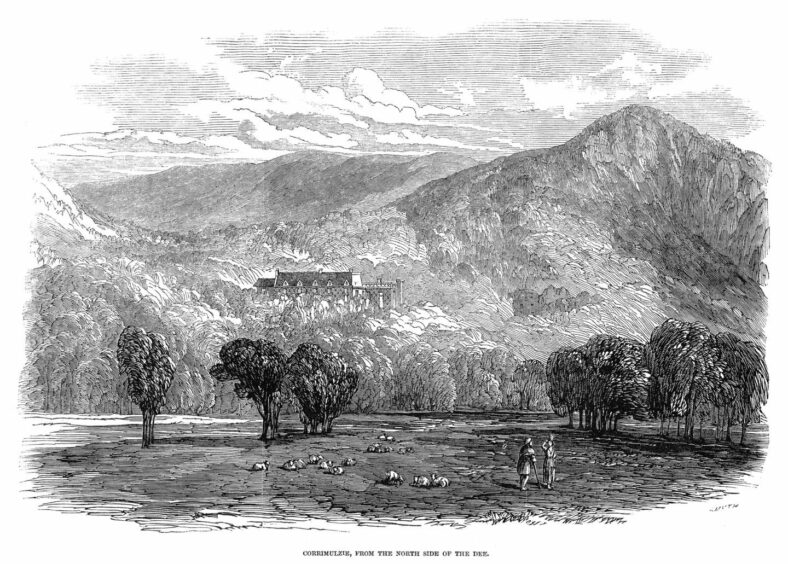

They were emigrating for better lives either voluntarily or, notoriously, at the hands of landowners replacing them with sheep.

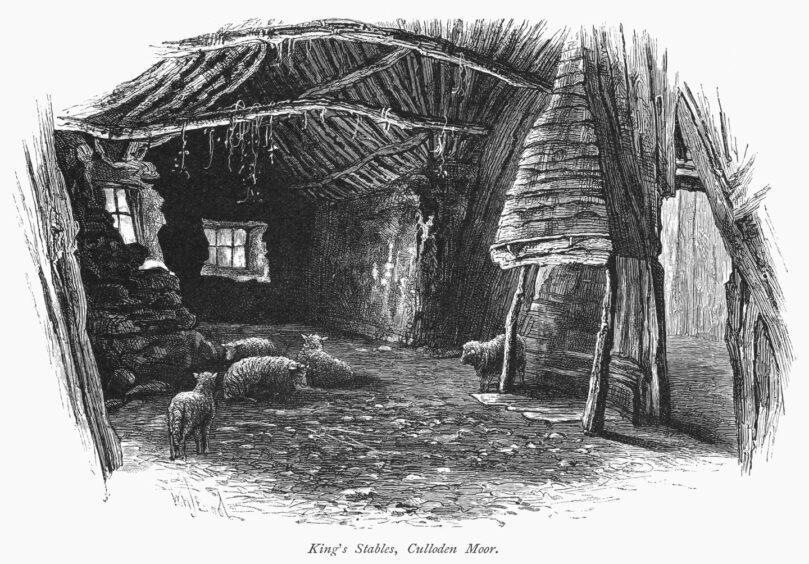

The squalor and poverty in which they lived is inconceivable to us now.

So how did the canal, which made up 22 miles of a 66-mile waterway down the Great Glen between Fort William and Inverness, create so much profound change?

It was clear to the ruling classes of the day that lack of infrastructure was the main hindrance to progress in the Highlands, and putting it in was the key to stopping mass emigration.

Telford commissioned to map out future Caledonian Canal

The government commissioned the greatest civil engineer of the age, Scotsman Thomas Telford to map out and cost up a canal down the Great Glen.

Battering through the many obstacles which could stand in the way of the canal, Telford charted its course.

Convinced, the government opened its coffers.

It had to keep on opening them for far longer than Telford initially proposed, but the commitment was there.

Its first benefit was to employ thousands of skilled and unskilled local labourers and spawn an ever-increasing plethora of support services upon which towns like Fort Augustus were built.

Real money was making its way into desperately poor homes, even if the labourers had to down tools (tools which incidentally they had to provide themselves) to go and get the harvest in or join the herring fleet.

Roads were built

Roads had to be built to service the canal operations, and these remain as the basic road network north of Inverness.

The canal took 18 years to build instead of the originally projected seven.

That’s almost two decades of employment for locals, and it didn’t stop there.

In one sense the canal was a failure, as by the time it was done, the age of rail was taking over transport and haulage.

The Napoleonic Wars were also over, meaning that safe passage for naval war ships was no longer needed, one of the early selling points of the canal.

Ships had also grown much larger, and the canal was best suited now for the herring fishing fleet and steam packets plying goods along it.

But no one had banked on tourism, and now another wave of opportunities kicked in.

The increased wealth brought about by the canal could be exploited by savvy families able to service the needs of the burgeoning number of visitors to their locality.

The P&J is celebrating the canal’s big birthday with a series of articles about it.

Join us by drone as we travel west from Inverness along Caledonian Canal

To start with, click the video above for spectacular drone footage of the journey from Inverness to Loch Ness, the most easterly section of the 66-mile waterway.

Scottish Canals look after the waterway, and staff member Ailsa Andrews explains the lock system.

Tomorrow, we look at the canal’s construction and appeal to you the reader, to help put names to those who wrought it out of stone and mud with their bare hands.

On Wednesday, we reveal snapshots of life on the canal over the past two centuries.

Conversation