It was the epidemic which erupted across the world in the 1980s and claimed the lives of such figures as actors Ian Charleson, Denholm Elliott and Anthony Perkins, ballet maestro Rudolf Nureyev and pop star Freddie Mercury.

Yet, even as Aids and HIV cast a blight over the lives of millions of people, the words of a poem called Tolerance, which were found in the wallet of a young American victim in 1987, reflected the desire of the gay community not to be stigmatised.

It read: “One of the most loveable qualities a person can possess is tolerance,

“It is the vision that enables me to see things from another’s viewpoint,

“It is the generosity that concedes to others the right to their peculiarities,

“And it is the ‘bigness’ to let people be happy in their own way instead of our way.”

Plenty of people in Aberdeen and across the north-east were ready to heed the message and raise Aids awareness and help those affected – but, even in 1990, there were others who resorted to homophobic abuse and described it as a “judgment from God”.

In 1984, scientists had identified the Human Immunodeficiency Virus – the organism which led to the development of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (Aids).

But although the United States Secretary of State for Health predicted that a cure would be found within the next two years, the search for new “miracle” drugs proved elusive and every month brought fresh cases of HIV infections in almost every country.

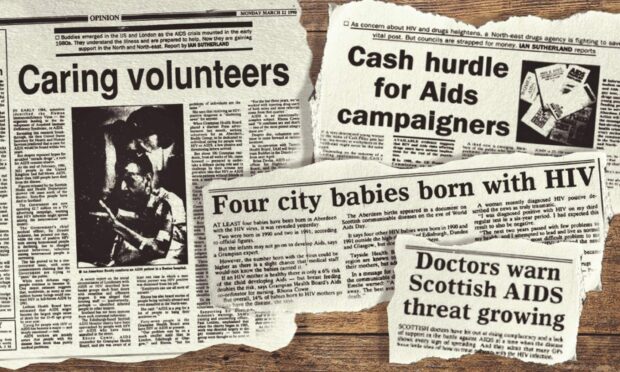

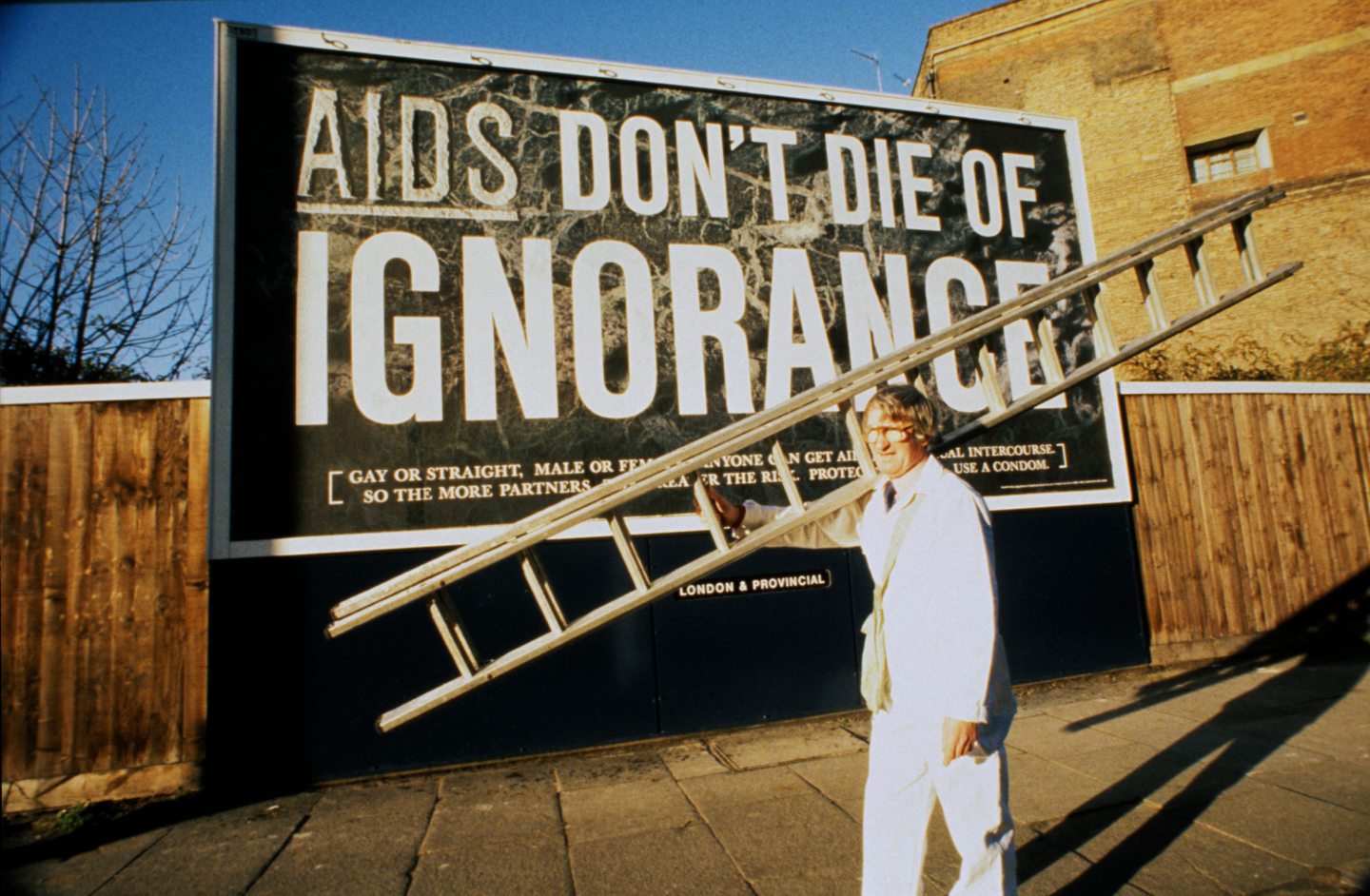

By 1990, the UK Government’s chief medical officer, Sir Donald Acheson, reported that while the rate of positive HIV tests among the homosexual community was declining, the rates of infection among heterosexual people were sharply increasing.

Ignorance and prejudice crashed head-on

Some lurid banner headlines in the tabloids were followed by far-right agitators in London and Edinburgh daubing swastikas and obscene slogans on the properties of those targeted for vilification – and Rhona Cowie, Aids counsellor for Grampian Health Board, told The Press and Journal she was aware of at least one case in which a man, whose PARTNER had been diagnosed as HIV-positive, was dismissed from his job.

Yet at least, amid such ignorant prejudice, others responded with a positive approach and the realisation that building bridges was better than smashing them to pieces.

The health board had placed a “discreet” press advertisement in February 1990, seeking volunteers for an Aberdeen Buddy Group, dedicated to providing individual care for those living with Aids or HIV and who were judged to be most vulnerable.

The P&J reported: “A few abusive and threatening letters arrived in response, but about 100 Grampian residents, from all walks of life, came forward, who were prepared to undertake a delicate caring role and challenge any prevailing idea that HIV or Aids inevitably leaves patients without friends or with a much-reduced quality of life.

“Buddies became active in the United States and in London as the Aids crisis mounted in the 1980s and the scheme has established a wide support network, for those who were either struggling with the disease or felt overwhelmed by a positive diagnosis.”

As Rhona Cowie said: “A Buddy is somebody who understands the illness and who understands that confidentiality is of prime importance.”

Aids could strike anybody

The initiative gradually increased the range of services it could offer and became a lifeline for many in the region, but the death of Bohemian Rhapsody singer Mercury towards the end of November 1991 served as a reminder that Aids could strike anybody.

And at the grassroots, although new treatments were being created, the concerns among young people in particular heightened as news spread of yet another celebrity succumbing to the illness which had become an emotionally-charged subject.

Ms Cowie told the P&J: “Our problem may be on a much smaller scale than in London, Glasgow or Edinburgh, but the problems for the individuals are the same and receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis is shattering news for anyone.

“It combines sex and death – two of the most potent images there are.”

And, soon enough, there was further disturbing news when The P&J revealed on its front page in September 1992 that babies had been born in Grampian with HIV.

In a report released on the eve of World Aids Day, it was confirmed that “at least four babies have been born in Aberdeen with the HIV virus. Two were born in 1990 and two in 1991, according to official figures”.

“However, the number born with the virus could be higher as there is a slight chance that medical staff would not know the babies carried it.”

Experts in the Grampian region confirmed: “If an HIV mother is healthy, there is only a 6% chance of the child developing Aids – but breastfeeding doubles the risk.”

One woman spoke of her ‘living hell’

Yet, behind the statistics, there were real people with often heartbreaking stories of how their lives had been ripped apart after being diagnosed with the disease.

One woman told The P&J: “The news I had HIV was truly traumatic and the most difficult problem for me was having to live with this threat hanging over me. There is very much a stigma attached to HIV/Aids and you feel the need for total anonymity.

“I kept hoping that the tests would come back negative, but then the timebomb exploded and I became extremely ill. I had full-blown Aids and it is a living hell.”

The P&J said the unnamed woman was still being kept alive by drugs.

The organisation Aberdeen Drugs Action was among those who worked hard to tackle the issue in the early 1990s, but were often hampered by financial constraints which meant they had to make very little money go an awful long way.

Cath Pilley took up the post of HIV and drugs worker with ADA in the summer of 1991 and, despite budgetary limitations, poured her heart and soul into her new role.

She created seminars for staff and inmates at Craiginches Prison in the city and provided a similar service for women’s groups. She also developed plans to promote better awareness of HIV and Aids among the general population, both to break down barriers and make it clear almost everybody was at risk from the disease.

As The P&J put it: “If a very determined young woman by the name of Cath Pilley gets her way, tea breaks at workplaces in the north-east may never be the same again.

“Depending on the outcome of a funding application by Cath’s employer (ADA), which will be considered at tomorrow’s meeting of Grampian Regional Council’s social work committee, workers in the area could find informal education on Aids, drugs usage and safe-sex practices on the canteen menu with egg and chips.”

The council chairman, Brian Balcombe, personally backed her campaign. But, in the end, he admitted there was almost no money to implement such bold proposals.

He said: “Aids is a very serious problem and unless we spend money now, we will pay the consequences later. But we are getting inundated with (funding) requests and we only have £38,000 to allocate to new applications – and that includes ADA.”

Advances in treatment

Since the discovery of HIV and Aids in the 1980s, a substantial number of advances have been made in its treatment, though it remains widespread in Africa in particular.

The virus, and its subsequent evolution into Aids, was once regarded as a death sentence and World Health Organisation figures show that upwards of 40 million people have succumbed to the disease: a horrific toll in anyone’s terms.

However, treatments today are so advanced that HIV is now a “very treatable and manageable infection” and people can live with the disease to old age.

The fight against the virus isn’t over – at least 35 million people across the world were reported as having HIV at the end of 2021 – but thankfully, the vast majority of attitudes towards Aids no longer remain stuck in the 1980s.

More like this:

How tatties and typhoid ham epidemic brought Aberdeen to a standstill

Conversation