It’s 25 years since the devastating death of Diana, Princess of Wales, in a motoring accident in Paris as she fled from pursuing paparazzi.

The news of her demise at the age of just 36 from the grievous injuries she sustained in a car crash in the Pont de l’Alma tunnel in the French capital on August 31 1997 was the catalyst for an unprecedented outpouring of public grief throughout the world, and her funeral at Westminster Abbey was watched by billions of people.

The Royal Family, including the Queen, were criticised in some sections of the press for their reaction to Diana’s passing, even as recently-elected Prime Minister Tony Blair was pivotal in the commemorations and describing Diana as “The People’s Princess.”

In a few weeks, the woman who had been cold-shouldered by the British media, following the collapse of her marriage to Prince Charles and the news of her relationship with Dodi Fayed – who also perished in Paris – was transformed into a saintly figure, millions of people signed condolence books and Elton John’s re-release of Candle In The Wind – with the title Goodbye England’s Rose – surged to No 1.

Princess Diana’s north-east connections discovered

But there was also a strong north-east connection to Diana which emerged in the aftermath of one of the most extraordinary chapters of modern British history.

The story went all the way to the early part of the 19th century and investigated the eight-year marriage from 1812 to 1820 of mixed-race couple, Theodore Forbes from Scotland, and Eliza Kewark, an Armenian woman from Gujarat in India, from whom the princess was directly descended.

And it was told in the book Theodore And Eliza by Susan Harvard, who received her early education in Findhorn in Moray and Kintore and Blackburn in Aberdeenshire.

She explained how Eliza met and married Mr Forbes, in the Mughal stronghold of Surat in India and described their life together in the Red Sea port of Mocha in Yemen.

At that stage, Mr Forbes was a political and commercial agent for the Honourable East India Company, whose duties included responsibility for the purchase and shipping of the entire annual consignment of coffee for Britain.

But the book also opened a window into some of the more colourful and controversial aspects of the British Empire, including his dealings with spies, pirates and the earliest European travellers into Africa and chronicled the direct relationship between the Forbes family of Boyndlie, the Crombies of Culter, who were the owners of the Cothal Mills, and Princess Diana’s family – the Spencers.

Mrs Harvard, who worked on the project for a quarter of a century, carried out a substantial amount of research and described as “remarkable” the amount of information which emerged from her being granted access to letters and archives and being helped on her journey by such places as Aberdeen University’s library.

Her work explained how Mr Forbes accepted a prestigious partnership with Forbes & Co in Bombay in the 19th century, but this new position meant that he was forced to choose between his career and his family.

Although he still loved her, he decided to leave his wife and their three children. But, in a poignant series of letters which were extensively quoted in the book, Eliza pleaded to be reunited with her husband.

A broken link in the genealogy of Diana

Eventually, he agreed to send their young daughter, Kitty, aged six, to his parents in Scotland.

It was there in Aberdeen that she “married well” to James Crombie of the international cloth company – the wedding was held at St Nicholas Kirk in the city – and the couple subsequently had a large family of their own.

Directly descended through the female line, in 1961 Kitty’s great-great-granddaughter, Countess Spencer, gave birth to the future Princess of Wales.

The inside story of the couple’s previously disputed union was drawn from their personal correspondence and other unpublished papers.

In 1820, Theodore died at sea, while he was on his way home to Scotland, aged just 32.

Here was another person in their 30s killed before their time while travelling.

Mrs Harvard added: “With modern DNA analysis, a broken link in the genealogy of Princess Diana has been put back together and I think that it is a fascinating story.

“The Crombies, and the wealth which their internationally-famous cloth generated were, of course, at the root of the family’s gradual rise up the social ladder.

“When Kitty married James, he gained a foothold into Aberdeen society and she gained financial stability and status as a married woman – she was no longer just a girl of questionable parentage from the East Indies.”

Story spans different continents

Katherine Crombie lived on until April 10, 1893, when she died at 16 Bon Accord Square in Aberdeen.

But, as Mrs Harvard’s book has illuminated, her legacy lives on.

Susan Harvard has spent the last 25 years investigating the history and genealogy among some of the most well-known Scottish families of the last 200 years while preparing her book Theodore And Eliza.

The author carried out extensive research into the many disparate strands of the story, which spans different continents and generations.

She said: “The book is strictly non-fiction and the romantic narrative is threaded into the cultural, political and social background.

“But, despite being the product of extensive research, it is aimed at the general reader.

“I am not Scottish – and I live in Somerset – but my early primary education was in Findhorn, Kintore, North Berwick and Blackburn, just outside Aberdeen.

“I have a great affection for the north-east and much of the research for the book was carried out in the special collections of King’s College Library at Aberdeen University.”

The book is available on Amazon.

More like this:

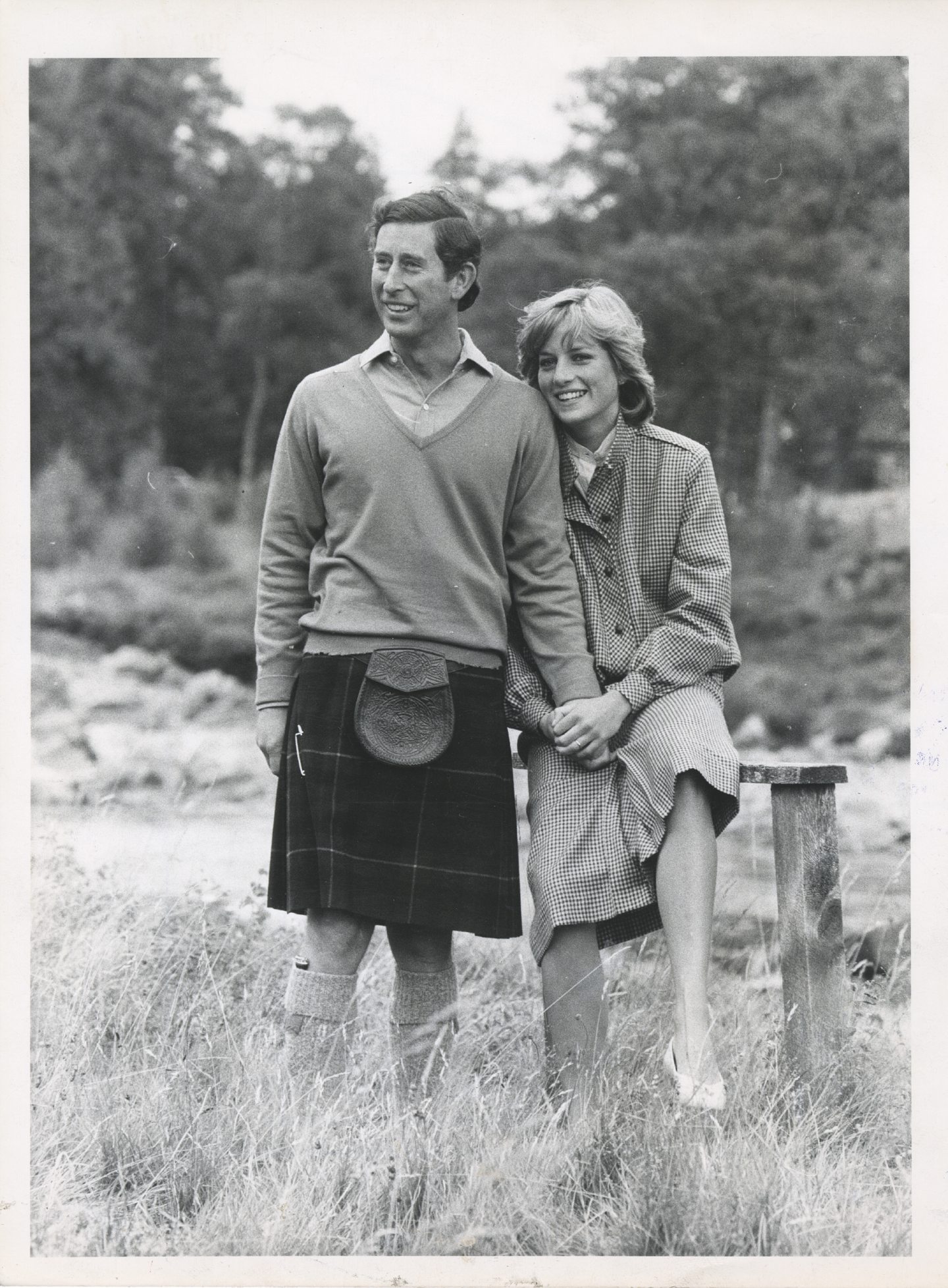

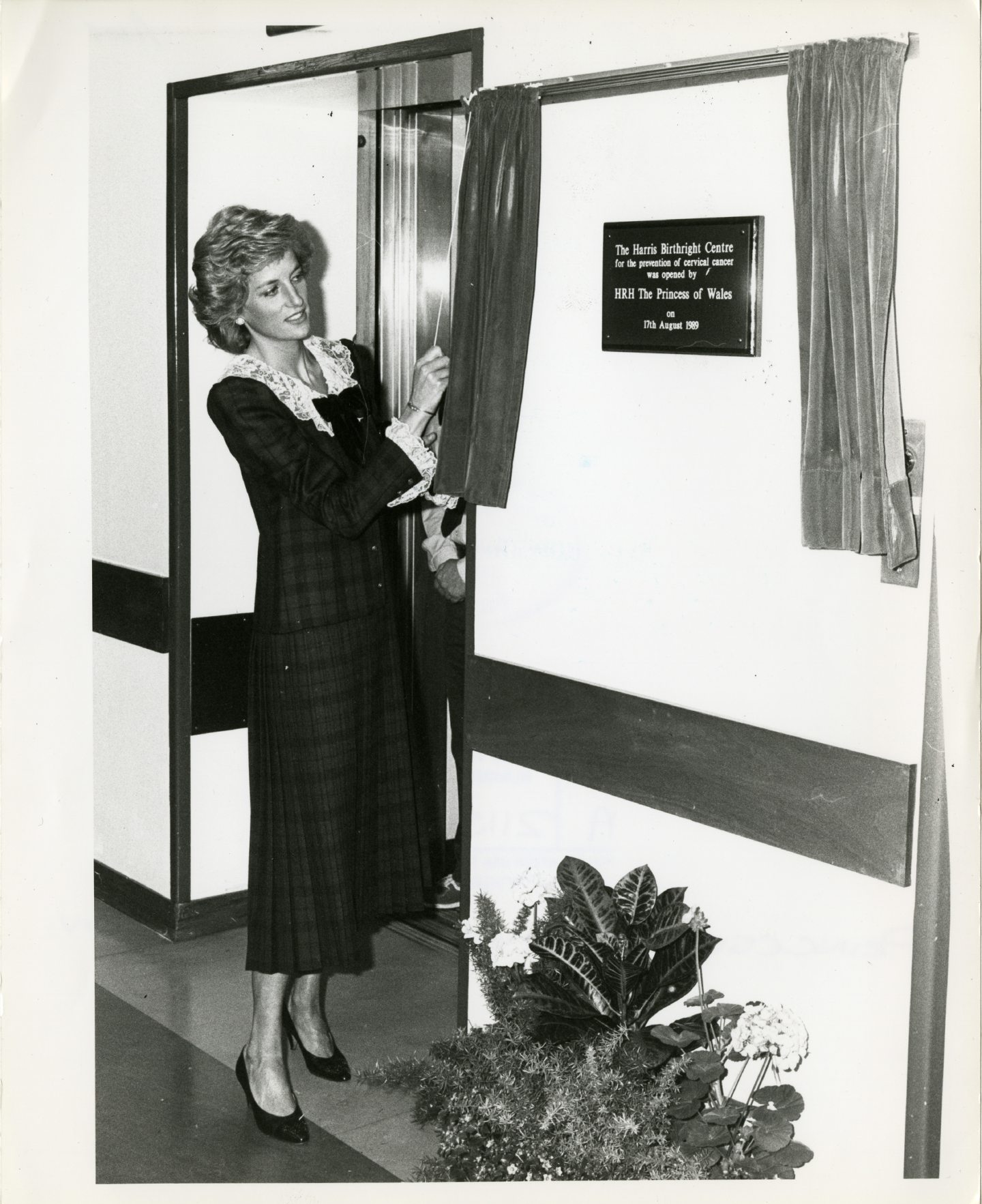

Princess Diana: Archive images of the people’s princess in Scotland

Braemar Gathering: Deeside’s royal jewel in the crown of the Highland Games

Conversation