It was a royal visit which brought a bold idea to fruition in Aberdeen.

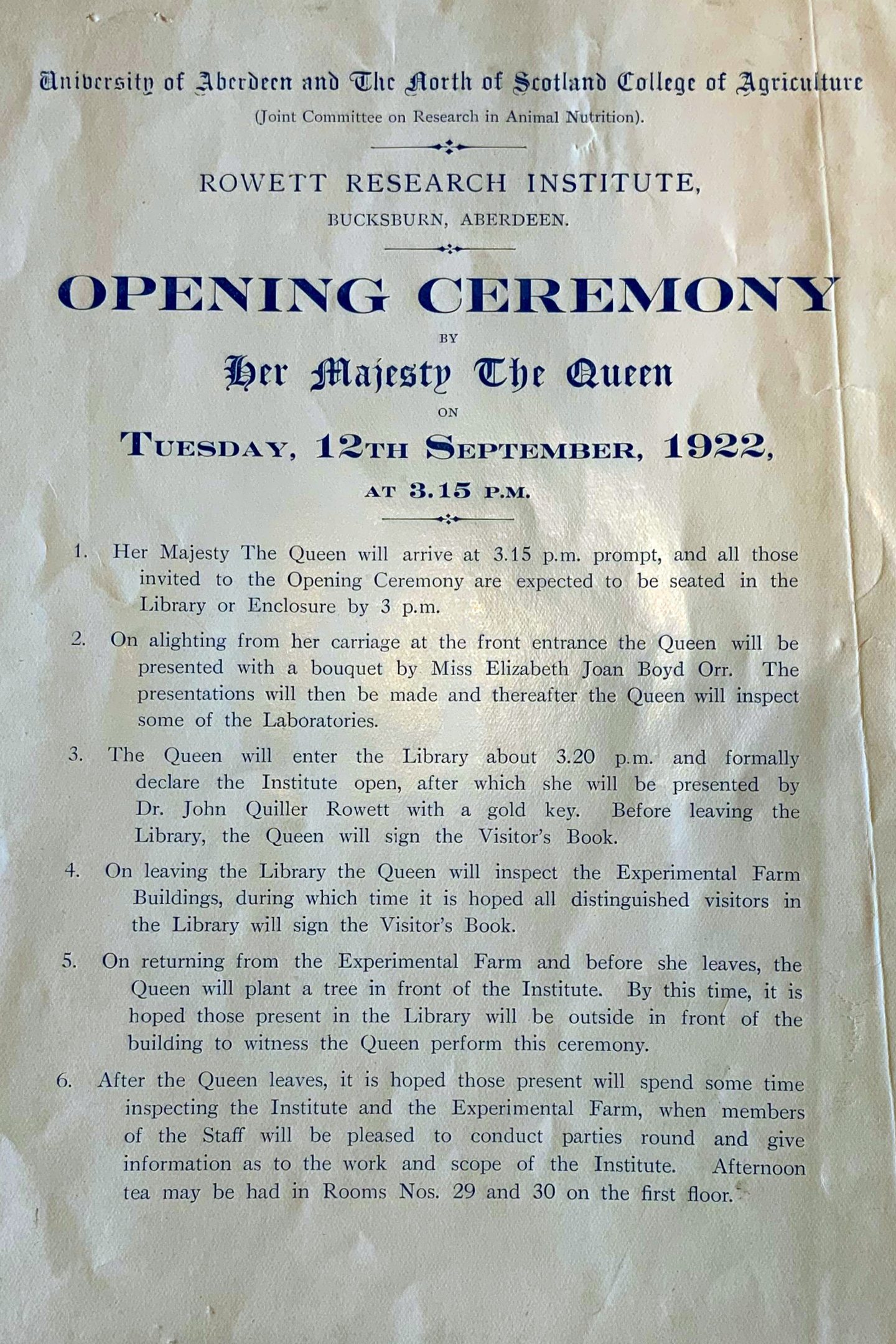

And when Queen Mary cut the ribbon at the Rowett Institute on September 12, 1922, it marked the start of a century of research to improve both animal and human health.

Since the laboratories opened their doors, this pioneering centre has enhanced the nation’s health through free school milk, underpinning wartime rationing and improving agricultural production. Today, it supports the food and drink industry to produce healthier foods and assess the sustainability of different types of food.

The development of the Rowett was originally driven by its founder, John Boyd Orr, one of Scotland’s most remarkable figures, whose determination, intellect and skill in persuading benefactors to part with considerable sums of money transformed the modest premises into a world-leading centre of research.

And his achievements earned him the Nobel Peace Prize for his effort to “conquer hunger and want, thereby helping to remove a major cause of military conflict and war”.

Orr spearheaded Rowett Institute construction

Orr, born in September 1880 in Ayshire, was a bright spark at school and won a bursary to Kilmarnock Academy. But he was more interested in the life of the navvies and quarrymen who worked in his father’s business than in his education and returned to the village school where he became a teacher.

However, it was not his preferred vocation and he eventually decided to go back to university to study biological science and medicine, which shaped the rest of his life as he relocated to the north-east of Scotland to take charge of an institute of nutrition.

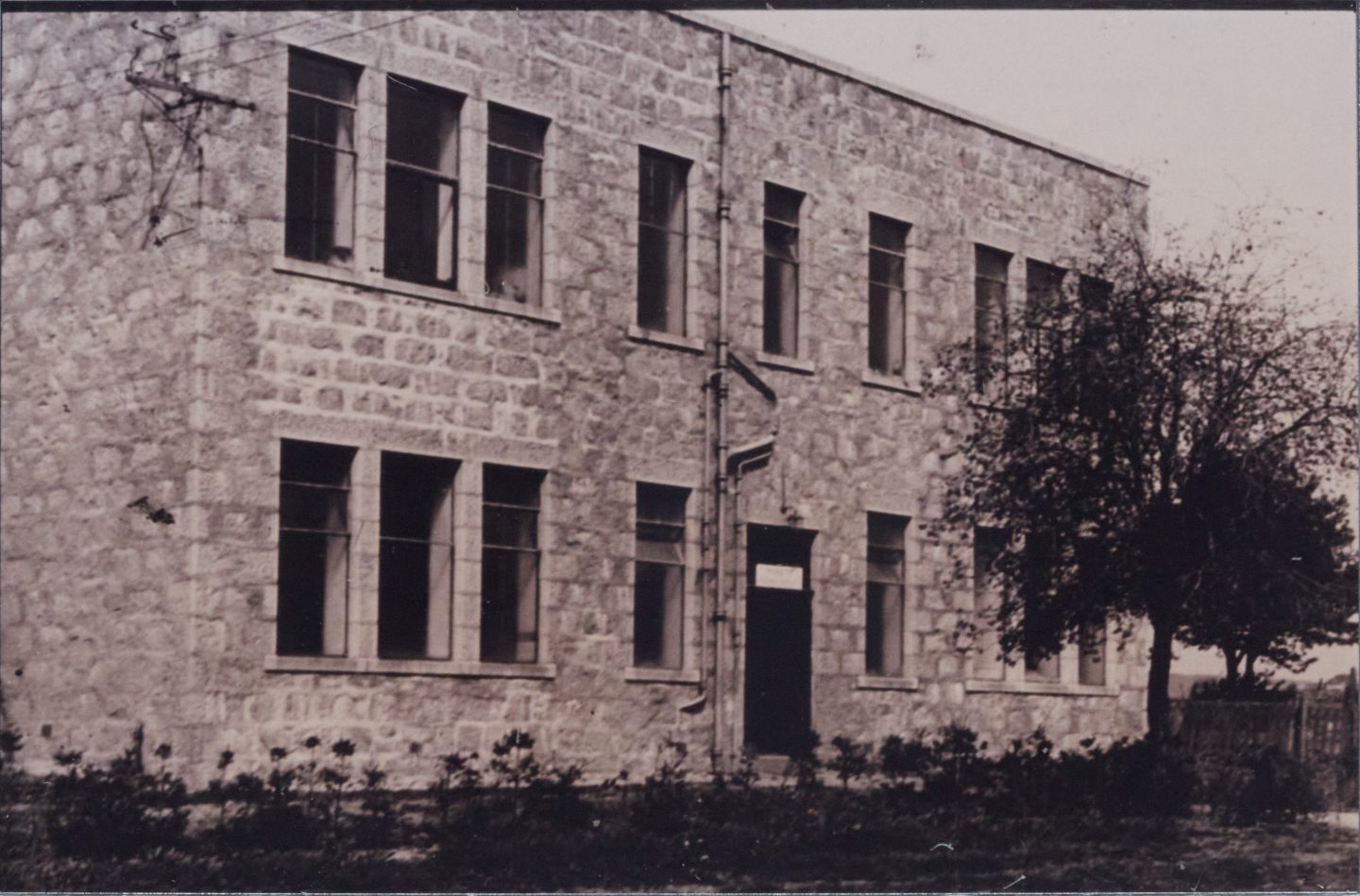

He arrived in Aberdeen on April 1, 1914, an appropriate date in the circumstances. After all, when he asked where the institute was, he discovered it did not yet exist! Instead, a sum of £5,000 had been set aside to construct a wooden laboratory at Craibstone with a further £1,500 annually for staff salaries and maintenance.

Orr viewed this as a wholly inadequate sum and set about transforming the plans. His own estimates totalled more than ten times his initial allocation.

Within his £5,000 budget, he costed and instructed a building of granite, rather than wood and by the time the committee next met, the walls of his new building, deliberately designed as the wing of a larger institute, were already six feet high.

Return from war did not halt campaign for change

But the swift progress was interrupted by the outbreak of war. Orr enlisted, initially assisting with improving sanitation in barracks before serving in the trenches as a medical officer to the 1st Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters.

At the Battle of the Somme, his battalion suffered heavy losses. Its strength was reduced from 800 to about 200 in just 24 hours, with the loss of nearly all its officers.

When those who remained were moved back from the frontline to boost numbers with new recruits, Orr took the opportunity to improve their health through diet and sent a fatigue party to collect vegetables from abandoned gardens and fields.

His biography observed: “As a result, from the men in his medical charge, he had to send none to hospital, whereas units who relied on their army rations without such supplements were much less fortunate.”

He continued to serve as medical officer at Ypres and Passchendaele, his courage under fire earning him both a Military Cross and Distinguished Service Order.

Yet, as soon as the Armistice was signed, he returned to Aberdeen and found that the walls and roof of the granite building had been completed, but there was still no acceptance of his idea of a larger ‘Institute for Nutritional Research’.

He appointed his first three staff members and, in the weeks that followed, the team used their own hands to fit the new laboratory with benches and equipment and, in their lunch hour, constructed an access road to the building from a nearby farm road.

By midsummer in 1919, all was complete, but Orr was not prepared to settle for such a small-scale facility and continued to push for a properly equipped new research institute. And finally, the Government agreed to pay half the costs.

This was crucial work in improving health

As for the rest, he soon put his persuasive powers to good use when he was introduced to John Quiller Rowett, a businessman and director of a wine and spirit merchants in London which had profited substantially from the war.

Rowett was impressed by Orr’s ambitions for the nationally important functions that an enlarged research institute would serve and his donation of £20,000 allowed the purchase of 41 acres of land at Bucksburn for the project to be built on and also contributed towards the cost of the buildings.

The money was donated with one crucial stipulation from Rowett: “If any work done at the Institute on animal nutrition were found to have a bearing on human nutrition, the Institute would be allowed to follow up this work.”

By September 1922, the construction was nearly complete. But when Orr learned that Queen Mary had agreed to travel from Balmoral to conduct a formal opening, a last-minute rush ensued as the facilities were far from ready for such a ceremony.

Importantly, there was not an adequate complement of animals available to fill the uncompleted pens. According to contemporary reports, the Queen said during the ceremony that the sheep looked tired.

She was right – they had been travelling all night.

Orr’s research proved link between poverty, poor diet and ill-health

Professor Peter Morgan, director of the Rowett from 1999 to 2021, said: “As a medic, Orr was able to run his own research interests in parallel with the research the Institute was originally set up to undertake.

“In the late 1920s, he began to look at the relationship between poverty, food and optimal health. His research changed our understanding of the relationship between diet and health – he was the first scientist to show that there was a link between poverty, poor diet and ill-health.”

Orr set up experiments on the value of milk to school children and discerned there was a marked improvement in their health and growth, particularly among those from the poorest households.

This underpinned a parliamentary bill to provide school children with free milk and spurred his desire for ‘a comprehensive food and agricultural policy based on human needs’, for which he lobbied hard throughout the early 1930s.

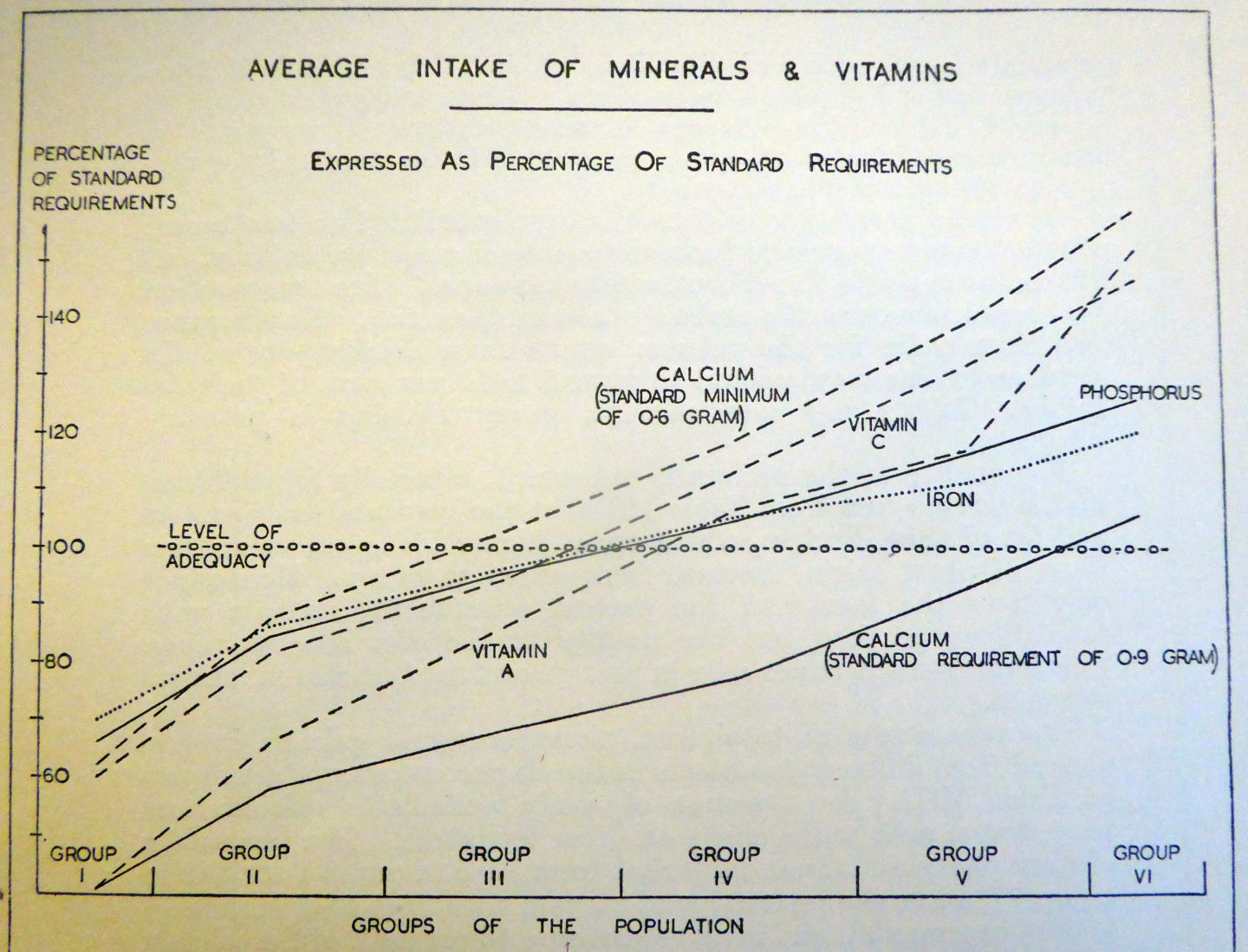

To support this, Orr led a study on ‘Food health and Income’, which classified the UK population into six groups according to income and then estimated the adequacy of the diet consumed in each of the groups. It showed that more than one third of the population was too poor to purchase an adequate selection of foods to maintain health.

So great was the interest in the 1936 study that the Carnegie Trust gave the Rowett a grant of £15,000 to carry out a wider investigation.

More than a thousand families took part across Scotland and England between 1937 and 1939. Detailed information was gathered on the socioeconomic status of each household and diet and data analysis was in progress at the Rowett when war broke out.

Orr, who had been knighted in 1935, joined a committee advising the Government on food policy and despite acute food shortages, their work ensured that women and children of the poorer classes were healthier at the end of the war than at the beginning.

In 1945, he retired from the Rowett and briefly served as an independent MP for the Scottish Universities before resigning the position in the following year to concentrate on his nutrition advocacy work.

At the end of the 1940s, his achievements were formally recognised. In 1949 he became a Freeman of the City of Aberdeen and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

His last public engagement came in 1970 when he opened a large extension to the Rowett’s laboratory facilities and he died in June 1971 at his home in Angus.

But what a legacy he has left behind.