There was no shortage of sacrifice as men and women took to the air in the early part of the 20th century.

Inspired by the Wright Brothers’ exploits in 1903, the dawn of the aviation age sparked the frantic development of a plethora of different flying machines, but some were more practical than others and their creators often paid a heavy price.

By the 1930s, though, in the build-up to the Second World War, an eclectic variety of remarkably sophisticated and formidable aircraft had been constructed across the world for both military and commercial purposes.

But still danger lurked for even experienced pilots, let alone youngsters who jumped into the cockpit.

And, as an example of how it could impact on families, there were few more tragic cases than the story of the MacRobert clan in the north-east of Scotland.

It’s a tale with chimes of Saving Private Ryan.

And yet, it was met with a remarkable act of generosity and the establishment of a legacy which exists to this day.

Rachel was a formidable woman

Rachel Workman was an extraordinary person in her own right.

Born in Massachusetts in 1884, she was a geologist, a philanthropist, a cattle breeder, a feminist…somebody whom, even when she married Aberdeen-born Alexander MacRobert, refused to attend the bestowal of a knighthood to her husband at Buckingham Palace in 1910, because she was a member of the suffragette movement and said boldly: “I will bow to no man”.

The couple had three children: Alasdair, the eldest, who was born in July 1912; Roderic in May 1915; and the youngest, Iain, in April 1917.

Their birth did not curtail Sir Alexander’s commitment to his business interests in India which led to his wife being left to care for the youngsters on her own and that became a permanent state of affairs when he suffered a fatal heart attack at Douneside in Aboyne in 1922.

Yet, undeterred, Lady MacRobert managed to continue her scientific investigations, run her late husband’s affairs and, when she learned her children were sickly, founded a herd of Friesian dairy cattle at her home to produce better quality milk for them.

This was her attitude to any number of obstacles and adversity; roll with the punches, get off the floor, dust yourself down and start all over again.

It was an approach she desperately needed as the 1930s progressed.

It was one disaster after another

Robert Jeffrey’s new book Scotland’s Wings examines the myriad people who risked their reputations, resources and lives to advance the development of flight.

And few of those chronicled in the work paid a higher price than the MacRobert brothers, all of whom were fascinated by soaring into the blue yonder and gazing down on the world.

Despite Lady MacRobert’s efforts to help her boys, fate had other plans for them. Not one or two, but the whole of the triumvirate who succumbed in similar ways.

Mr Jeffrey said: “Alasdair was killed, aged just 26, in a civil flying accident.

“The baronetcy (which had been given to Alexander MacRobert shortly before his death) was passed to Roderic, who was a pilot in the RAF.

“He flew Hurricanes and died in one such aircraft while he was leading an attack on a German-held airfield. He was also only 26.

“The baronetcy then passed to Iain, who was a pilot officer in the RAF having joined the force straight out of Cambridge. Against all the odds, the MacRoberts suffered a third tragedy in a row when, just six weeks after Roderic’s death, Iain’s Blenheim failed to return from a search and rescue mission from Sullom Voe in Shetland.

“His body was never found. He was only 24 years old.”

One can hardly imagine the devastation which these events must have caused Lady MacRobert, who had barely finished burying one son before having to organise another funeral. It would have been perfectly understandable if she had chosen to cut herself off from the world and mourn in private.

But, as you might expect from this resilient character, she wasn’t prepared to let anything grind her down.

Rachel’s response was remarkable

As Mr Jeffrey explained: “The response of Rachel to these tragedies was remarkable: she made a gift of £25,000 to the RAF and asked them to use it to buy a bomber to be called MacRobert’s Reply.

“A Short Stirling bomber, handed over to the RAF late in 1941, was duly given this name, and it took part in 12 missions.

“However, it was damaged in a collision with a Spitfire at Peterhead airbase and replaced by another Stirling which carried the name.

“This plane was shot down and lost in a minelaying raid in 1942, but following her original donation, Rachel then gifted a further £20,000 to help buy four Hurricanes to aid the RAF in the Middle East. These were named after her sons and the fourth was given her own name.”

Given the privations she had suffered, it was a fitting tribute. But Lady MacRobert was not yet done with ensuring that others would be helped after she herself was gone.

There is a wonderfully short, sharp paragraph in a summation of her life as scientist, benefactor and all-round champion of myriad causes.

It reads: “At Lady MacRobert’s attendance in 1913 at the Annual General Meeting of the Royal Geological Society an attempt was made to eject her; it did not succeed.”

On the contrary, she always stood up for causes in which she believed, whether or not they were controversial.

‘MacRobert family will never be forgotten’

Decades earlier, when suffragettes were involved in violent protests in Aberdeen during 1913 against the conditions imposed on women, she justified actions such as explosives being thrown by stating: “Girls have no sort of life under present social conditions and the wickedness of men at large”.

By the end of the war, she was in her 60s, but her commitment to social change and philanthropy remained as potent as ever.

If anything, as this force of nature neared the end of her days – she died in 1954, aged 70 – Rachel redoubled her efforts and, even while grieving the loss of her sons, never forgot how so many others had struggled.

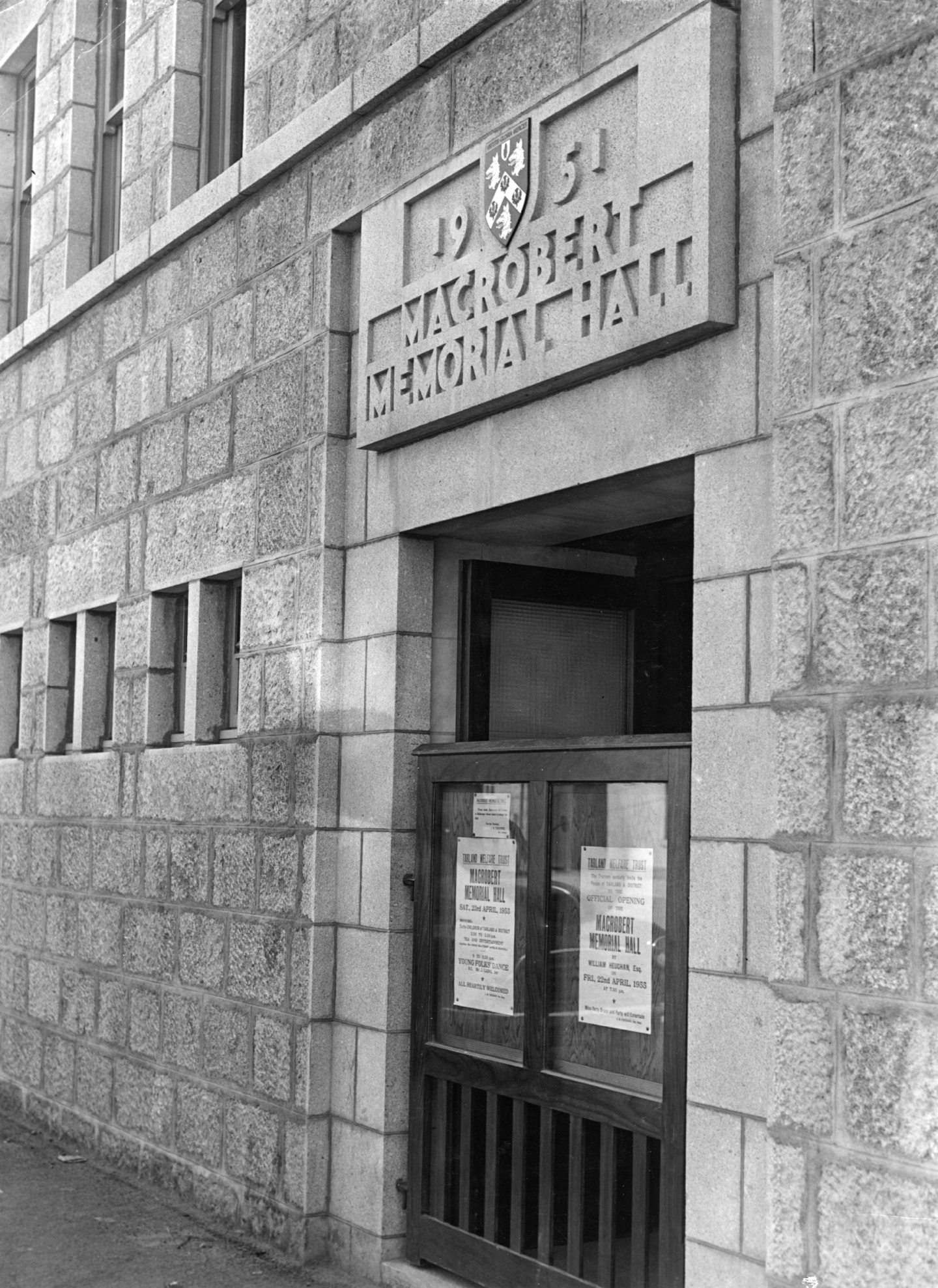

Mr Jeffrey said: “Between 1943 and 1950, Lady MacRobert founded a series of charity trusts to ‘provide the means and organisation to foster in young people the best traditional ideals and spirit’ which, she believed, had prompted so many young people, including Alasdair, Roderic and Iain, to fight in the Second World War.”

In 1943, she set up the MacRobert Trust, a charity that continues to support the RAF and other institutions. It created the MacRobert Award for engineering, which is now awarded by the Royal Academy of Engineering.

No wonder, as Mr Jeffrey concludes: “The MacRobert family will never be forgotten”.

Scotland’s Wings is published by Black & White.

Conversation