Brian Binnie never forgot the conversation he had with his mother when he was just seven years of age.

At that stage, while growing up in Milltimber in Aberdeen, the youngster was increasingly excited by the development of rockets and modules which were being despatched into space as the United States and the Soviet Union vied for propaganda victories and extra-terrestrial triumphs.

And eventually, the man, who has died aged 69 in the United States, not only realised his dream, but worked with Neil Armstrong, the first man on the moon in 1969.

Science was in Brian’s DNA – his father, William, was a physicist at Aberdeen University and he returned to the institution to receive an honorary degree in 2006 – and he grew up in the late 1950s and 1960s during the period when Sputnik was launched in 1957.

This was an exhilarating time for the child who was captivated by planes, jets and aircraft – and made history by becoming the first Scot to travel into space in 2004 – but his epic journey to the stars began when the idea was planted in his head by his mum.

He recalled: “While I had a fascination with things that fly, she was the one, when I was about seven, who asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up.

“I struggled to find an answer and so she interrupted me with the words: ‘If I was a wee laddie, I would want to be an astronaut.’

“And since I didn’t know what she meant, she went on to tell me about rockets and space, about planets and stars. And I was hooked from that moment on.”

Brian, whose family released a statement confirming his death, spoke to the Press & Journal about those momentous exploits in the 1960s with the breathless enthusiasm of somebody in thrall to space exploration.

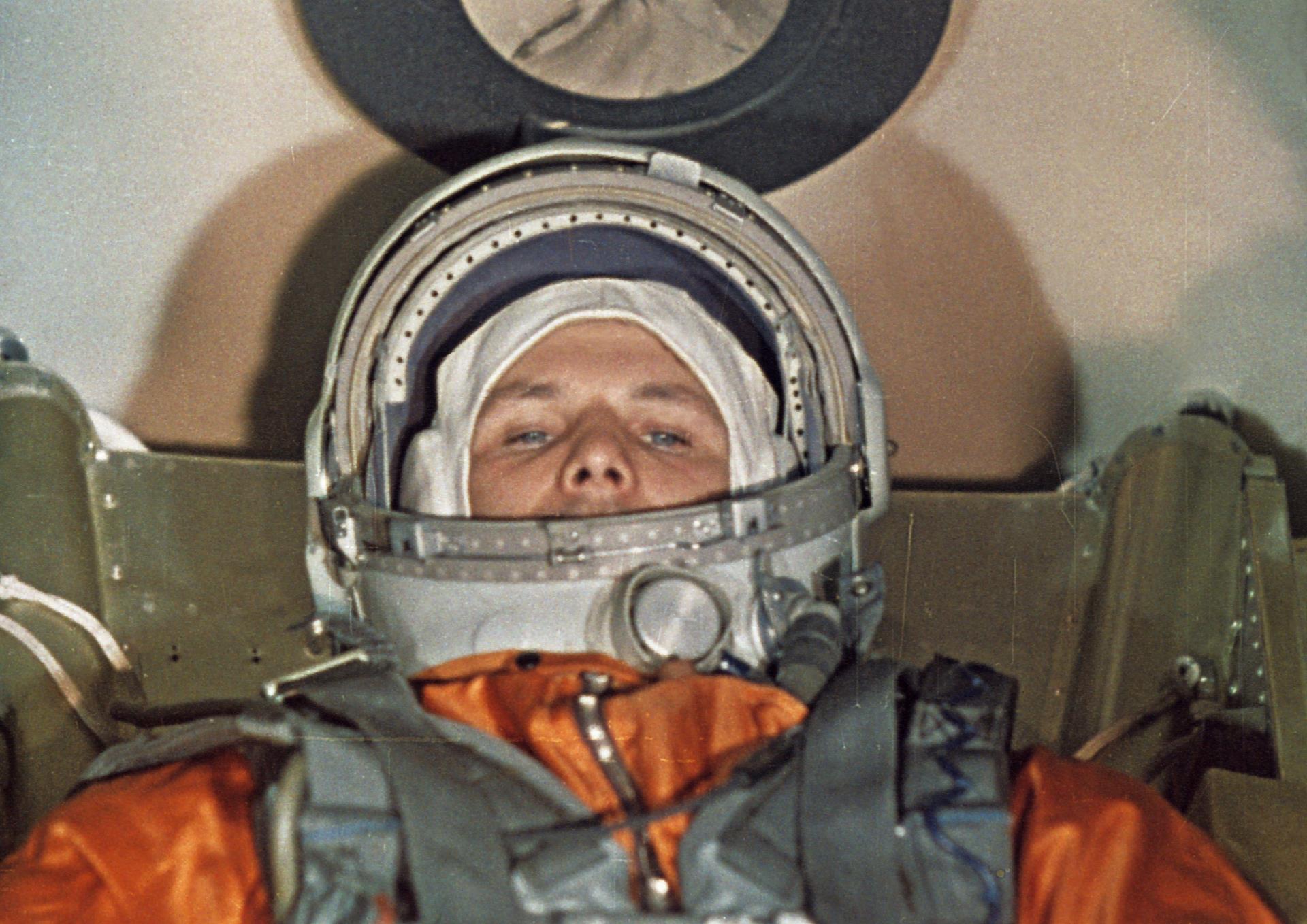

He told me: “Yuri’s flight was certainly an attention-getter, but Sputnik had a greater impact. The US was already spooled up and, with a few different management decisions, it could easily have been Alan Shepard up there first [the American made his trek into space three weeks after Gagarin].

“I don’t really know how the USSR picked their astronauts [or cosmonauts in the Russian parlance], but there is no doubt that they had to be fine physical specimens with an unexcitable temperament.

“The Russians were also notorious for maintaining command and control of things on the ground and taking away from their astronauts – and military pilots – many options for override control as the US astronauts demanded.

“It was a time when many things happened very quickly. There was, of course, the success of Gagarin, then shortly thereafter, they launched the first female [Valentina Tereshkova] into space in 1963. And that rattled NASA as much as anything.”

He marvelled at how the early spacemen and women transcended innumerable obstacles, even if there were tragedies along the way.

And he recalled: “The race to put men on the moon was incredibly ambitious. President John F Kennedy announced the challenge to put a man on the moon and bring him back before the end of the decade in 1961.

“The programme went through the Mercury flights, the Gemini flights, and was preparing for the first Apollo mission in January 1967 when a fire broke out and killed all three astronauts on the launch pad.

“It was a terrible thing. And yet, the fact that NASA recovered from that tragedy to Neil Armstrong’s ‘one small step’ in 1969 is astounding.

“Huge risks were taken to completely redesign the capsule and Apollo 8 was another milestone flight to demonstrate translunar injection.

“Meanwhile, Armstrong was learning to fly the LEM [lunar excursion module] flight simulator, ejecting once when the craft became unstable.

“The amount of fuel which was available to Armstrong and Aldrin to set the LEM down [on the moon surface] was not generous and the manoeuvring he was required to accomplish to find a suitable touchdown site left only seconds of reserve fuel.

“As [NASA’s] Charlie Duke said after the touchdown – ‘you had a bunch of folk down here turning blue’ – because they were literally holding their breath.

“But it succeeded, it worked, and it changed the course of history.”

As an experienced and well-regarded aviator, Mr Binnie first arrived in the Mojave Desert in California when he was hired as a test pilot by the Rotary Rocket Company, an organisation which was striving to develop a commercial spaceship which would land using a helicopter-style rotor blade system.

He helped develop the craft to the stage where it could fly but, when the firm shut down, he moved in 2000 to work for Scaled Composites, the leaders of the private space programme and his dreams moved closer to reality.

The clock was ticking on his dream

As he said: “It was the chance of a lifetime and I knew that I wasn’t going to get a second opportunity.” He was in his 50s: it was literally a case of now or never.

But then, on October 4, 2004, he made his historic flight in SpaceShipOne [the project financed by aerospace engineer and entrepreneur Burt Rutan]. The craft went higher than it had ever gone before in previous test flights and, in the process, accentuated the possibility of commercial space flight.

He gained several aviation and aerospace degrees, spent more than 20 years as a Navy test pilot and four years in the process of developing the world’s original commercial passenger vessel – SpaceShipOne – before becoming Scotland’s first astronaut.

His family posted on his Facebook page: “With overwhelming grief, sadness and sorrow, we announce the passing of our beloved Brian.

“We kindly ask for privacy during this time for our family to grieve the loss of our husband, father, brother and friend.”

The statement added that arrangements are being made for him to be laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

It’s fewer than three-score-and-ten years since Sputnik was followed by the heroics of Gagarin and Shepard, Tereshkova and Armstrong and, more recently, astronauts such as Chris Hadfield and Tim Peake.

If space truly is the final frontier, Mr Binnie explained why it’s worth it. “It is a fantastic view, a terrific feeling. There is a sense of wonder that we all need to experience.

“You can see as many pictures and videos as you like, but none of them do it justice when you look out and see the Earth, and all that separates it from the black void of space is the thin blue electric light of atmosphere.”

He was excited by space as a youngster

Brian was awarded an honorary degree in 2006 by Aberdeen University, where his father lectured while his son was growing up in Scotland. It remains one of his proudest moments and he talked about his early days in the north east of Scotland.

He said: “Even though I was born in Indiana, everyone else in the family is Scottish born, so I consider myself a true blood Scot whose formative years were spent roaming around the countryside where I grew up near Aberdeen.”

“I used to look up at the big skies you had in that part of Scotland and I was fascinated by the idea that, one day, I might go up there.”

He is survived by his wife, Bub, and their three children, Justin, Jonathan and Jennifer.