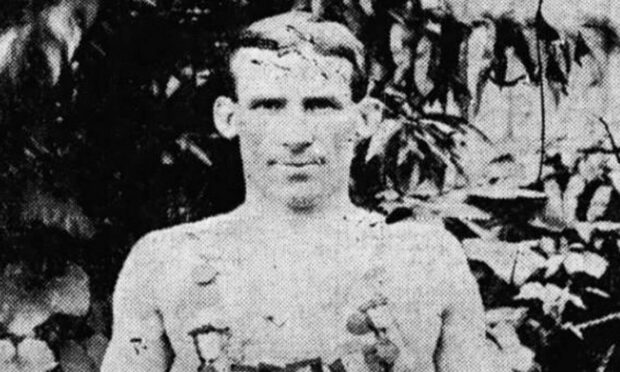

His name isn’t well known now, but there was a time when Adam Beattie Gunn was one of the most celebrated athletes in all the world.

The man, who could turn his hand to just about anything, excelled in boxing, wrestling, leaping, sprinting, bowling… some even joked that you could throw him an umbrella and he’d find a way of playing it and mastering it, just as he did with the many hulking brutes who boasted they would beat him and ended up with egg on their face.

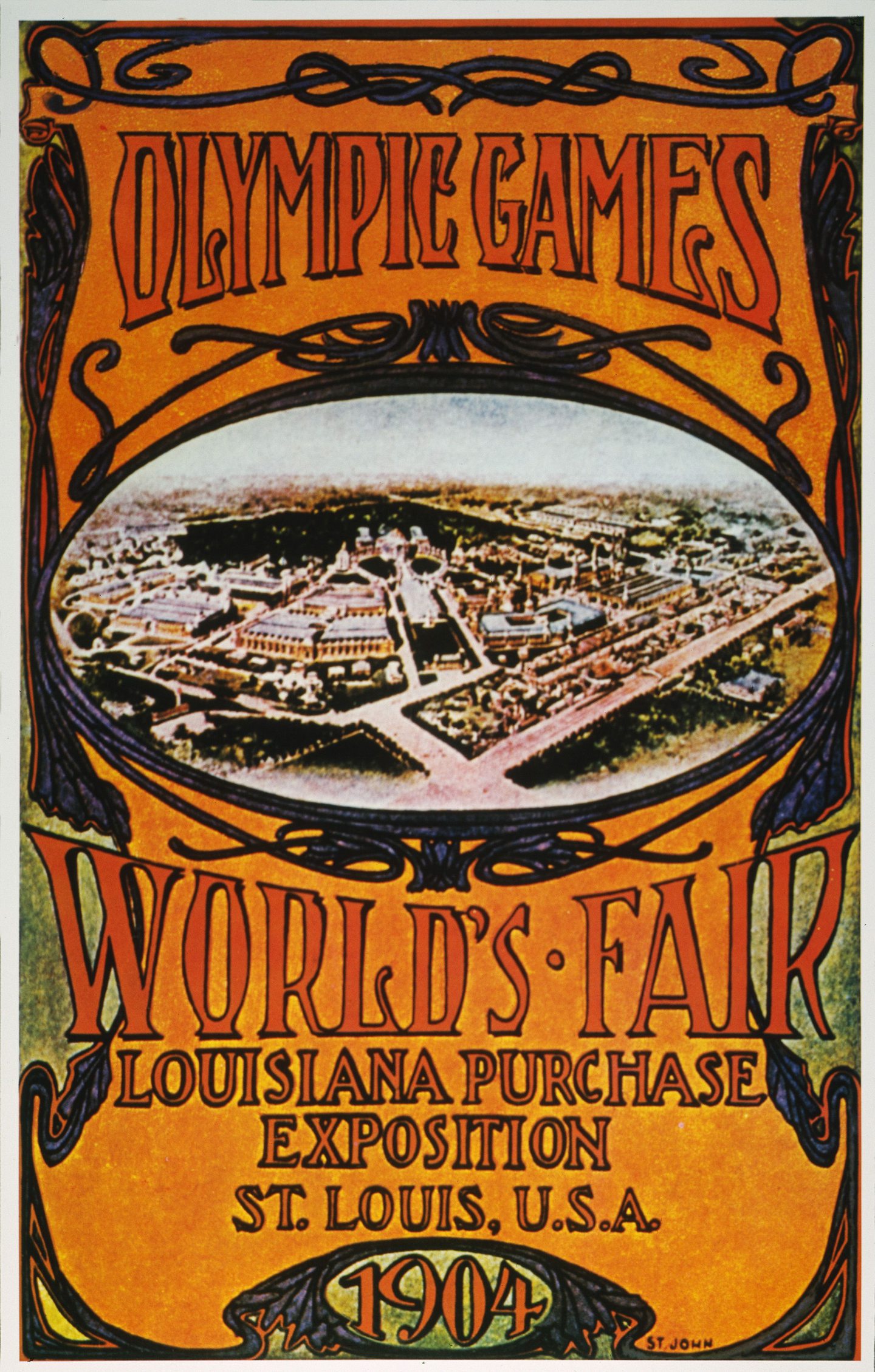

His strongest suit was the all-round competition which gradually evolved into what we know as the modern decathlon and Gunn was sufficiently talented in a plethora of different disciplines that he not only represented the United States at the 1904 Olympics in St Louis, but finished with a silver medal in his possession.

But who was this fellow who lived and worked in Buffalo in New York? What was his background and how had he become one of the most fearsome performers of his age?

Well, for starters, he wasn’t American at all, but a Scot, born and bred in the Highland village of Golspie – and, wherever he travelled, he never forgot his history and heritage.

He set off to vandalise a hated statue

Even as he was growing up, Gunn was no respecter of tradition or the notion of bowing to his so-called betters. In 1886, the teenager climbed the nearby Ben Bhraggie with, as one report put it, “mischief on his mind and a chisel in his hand”.

His target was the controversial memorial built in the mid-1800s in honour of the First Duke of Sutherland. This statue to the “Mannie”, as some folk who cannot bear to use his name call it, looms large over the community and Gunn was determined to make his mark on the individual who earned notoriety for his part in the Highland Clearances.

The Gunn clan had been among the many families who had suffered at the Duke’s hands, but Adam’s father, John, realised there was no point in his son continuing to live in a place where he harboured a destructive grudge. Soon enough, he was on a boat sailing across the Atlantic in search of a new life and secure employment.

And, in a matter of months, he was wowing his new-found friends and rivals with feats of athletic prowess, even as he found work at the General Electric power company.

If he had hailed from a different background, Gunn would have been a stellar figure on the Highland Games circuit in his homeland. As it was, he quickly gained a reputation as being able to pulverise opponents with his relentless attitude and incredible stamina – which was required when you were competing in 10 disciplines in a single day.

The events were the 100-yard dash, the shot put, the high jump, a walking race of 880 yards, a hammer throw, the pole vault, the 120-yard high hurdles, the 56-pound weight throw, the broad [long] jump and a one-mile run to round off the proceedings.

This would have been a gruelling schedule for well-paid professionals on strict training regimens, but there was no access to such luxuries 120 years ago. Instead, Gunn and his contemporaries were all amateurs, who had to fit their sport in around their work and rely on the benevolence of their paymasters to grant them an occasional day or two off.

Not that this was any obstacle to success as he reached his peak at the start of the 20th Century. He won the US championship in both 1901 and 1902 and there was much excited chatter in the American media about his prodigious feats in track and field.

He had missed the Olympics in 1896 and 1900 – what chance did he have of travelling to either Athens or Paris? – but the 1904 festival was being held in St Louis in Missouri. This was an opportunity he couldn’t afford to squander. And he didn’t.

Another time and a different age

Gunn, a man who preferred actions to words and who wasn’t inclined to engage in the trash talk which Games promoters loved in these days, was among the favourites to strike gold in what was billed by the IOC as the “all-around” contest.

But there were plenty of potent challengers in the field, not least Ireland’s Tom Kiely, who was another giant figure and subsequently dominated a stack of competitions.

This dynamic duo were pitted against the reigning US champion Ellery Clark, along with the likes of Truxton Hare, John Holloway and Max Emmerich, but such was the strength of the home participants that their press were sure they would triumph.

Gunn blasted out of the blocks at the outset and was bolstered by Kiely’s surprisingly poor showing in the early events. But the longer the contest continued, the more it became evident that the adopted Scot, at 32, wasn’t quite the force he had been three or four years earlier in his career. It was small margins, but with big consequences.

He came first in the shot put and the pole vault, but Kiely’s series of wins in the 880-yard walking race, hammer throw, 120-yard high-hurdles, 56-pound weight throw and broad jump gave him an unbeatable score of 6,036 points.

Gunn took the silver with 5,907 and Hare’s 5,813 was sufficient for a bronze. In some respects, it was a disappointing outcome, but he had his medal, he had pushed himself to the limit and he recognised he would have to get moving to return to work.

And, of course, he was still a hero among those who had followed his exploits.

There was no time for celebrations and no need to fulfil media requests in these days. Instead, Gunn was soon in his office at the power company, where he plied his trade for four decades, eventually becoming superintendent of repairs and a “radio noise detective” who used the latest equipment to find sources of unwanted static.

For his admirers, he was always an Olympic stalwart, but he never made much fuss about his achievement. He loved sport for its own sake until his death in 1935.

There are one or two indications of his roots when you visit Golspie – as I did a few weeks ago – and was intrigued by references to the “famous Adam Gunn”. But….

One contemporary report said: “If you are ever in Golspie, and visit the [Duke of Sutherland] memorial, you may want to look closely at the base upon which the statue rests. Possibly, just possibly, you may still see the place where, in 1886, a Scottish lad defaced the memorial by carving into it his own name – Adam Beattie Gunn.”

Nobody’s condoning vandalism.

But perhaps it’s about time this accomplished performer’s achievements were more widely known in his homeland.

Conversation