As the bonfire season approaches, lighting fires for ceremonial reasons comes to the fore as something humans love to do.

Lighting them atop the highest point also seems irresistible, Ben Nevis in Scotland, Skiddaw in the Lake District and Snowdon in Wales being coveted locations.

Author Tom Welsh wrote about the bonfire obsession in his new book, Hilltop Bonfires – Marking Royal Events.

He says Scotland led the way in placing celebration bonfires in high and hard-to-reach places long before what he calls the Bonfire Movement of 1856 got underway.

Royal visit in 1842

Queen Victoria’s visit to Scotland in September 1842 was the catalyst for an attempt to light a fire atop Ben Nevis.

Tom said: “There has long been a custom in Scotland to light bonfires on hilltops as a way of celebrating marriages, births and the coming-of-age of heirs to estates.

“When Queen Victoria visited Scotland in August 1842, fires were lit on hilltops for twenty to thirty miles in all directions around Edinburgh while the royal fleet was moored in the Forth Estuary.

“When she reached the Tay estuary in 1844, on her journey to Blair Castle, bonfires were lit on the hills on both sides of the Tay.

“Such displays of loyalty aroused a great deal of interest in the newspapers, and descriptions were relayed around the south of England.

“It inspired English estates to adopt the same mode of celebration.”

So what was involved in lighting a beacon atop the 4,400ft Ben Nevis?

The challenge of Nevis

People have pushed pianos up the Ben, indeed Highland Games athlete Kenny Campbell claimed he carried a church organ up in 1971.

No one’s been daft enough to push a brussels sprout up Nevis with his nose, as Stuart Kettel did in 2013 on Snowdon, but there have been some pretty flippant duels with the dangerous Ben over the years.

But the 1842 Royal bonfire was “activated by a keen spirit of loyalty, activity and perseverance,” Tom writes.

“Tar barrels and other materials were, with much difficulty and danger, conveyed to the top of ‘old Ben’.”

But in 1871, a row broke out about where the bonfire actually was, on the lower slopes or the actual summit?

This time the occasion was Princess Louisa’s marriage to the Marquis of Lorne.

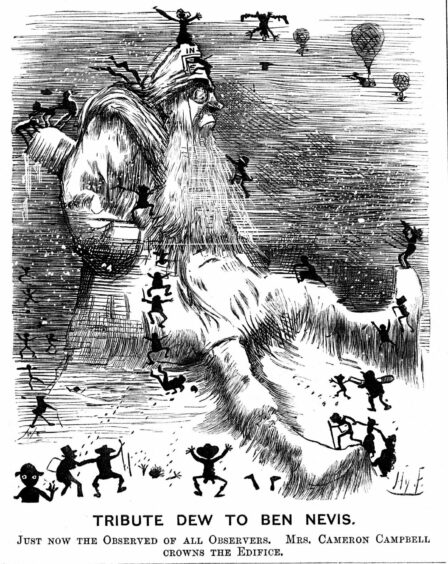

It was agreed that for their celebration, a huge bonfire composed of peat and wood saturated with paraffin would be lit on the summit, on land owned by a Mrs Cameron-Campbell.

She provided her tenants and sixteen horses to carry up the materials.

The location was then changed, to the Meall an-t-Suidhe western ridge so that it could be seen far and wide, unlike the main summit.

According to a contemporary account, the bonfire was composed of nine empty tar barrels, two cart-loads of dried peat blocks and the remains of two old fishing boats, broken up.

Things didn’t go particularly smoothly, the weather for starters.

Mist obscured everything, but that didn’t stop the local press from filling in the gaps.

One account claimed the tar barrels were full of tar and proceeded to burst in the heat, flowing down the mountainside and scorching the vegetation.

Others said the bonfire was actually on the Ben Nevis summit.

Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee

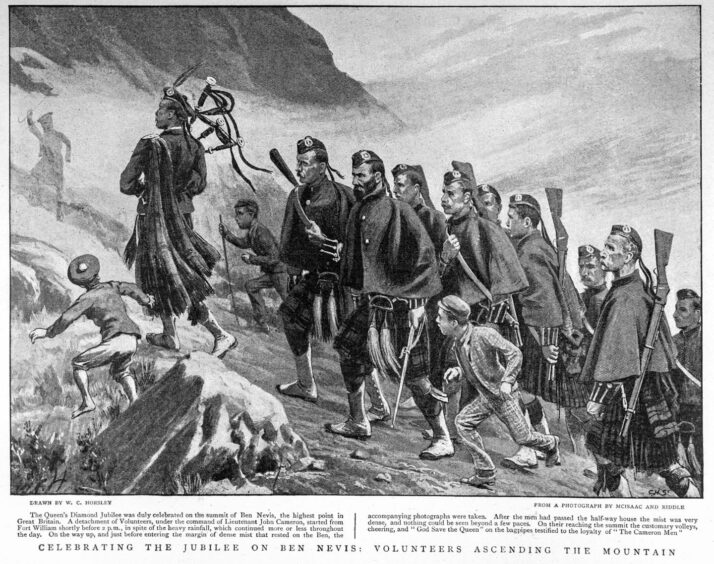

Matters had improved some 26 years later in 1897 on the occasion of the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria.

A track to the summit had been put in place in 1883, leading up to a residential meteorological observatory.

From 1895, people had started to run up the Ben and undertake various stunts.

For the 1897 bonfire, it took a couple of weeks for horses and men, again supplied by Mrs Cameron Campbell, to haul materials up to the top.

Brushwood came from the neighbouring deer forest in Glen Nevis, and peat was plundered from the local mosses.

Telegraph link

Tom said: “It was also the intention of Mrs Cameron-Campbell to signal the time to light by the telegraph wire for the observatory, so that it would be linked in with the national beacon programme.

“At 10.25pm signal rockets were sent up to forewarn neighbouring bonfire sites to be ready and at 10.30 the Ben Nevis bonfire burst into flame.”

The great Nevis Royal bonfire tradition stalled in the early part of the 20th century.

Bad weather prevented one for the delayed coronation of Edward VIII.

Nothing happened for the coronation of George V in 1911, although the intention seemed to have been there.

For George V’s Jubilee in 1935, there was grand talk of two bonfires, one on the summit and one on Meall a-t-Suidhe.

A job for the Boy Scouts

Boy Scouts, contentiously, were proposed for the task, which included the installation of a telephone on the summit to alert the King on Jubilee Day.

Once again bad weather foiled the plans, but the Boy Scouts managed to provide a small firework display on the summit.

The subsequent two Royal bonfires, in 1953 for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, and her Silver Jubilee in 1977, were barely recorded.

Bonfires to beacons

Most recently, the Royal bonfires have become beacons, Tom says.

“For the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012, a gas burner and cylinders were carried up and lit on top of the summit cairn to the accompaniment of bagpipes, likewise in 2022 in ventures organised by charities for ex-servicemen.”

You might enjoy:

Conversation