Frankly, you’re not going to argue with Clare Findlay. When she wants to achieve something, she’ll do it regardless of naysayers and obstacles.

Even if it means moving heaven and earth to accommodate an astonishing number of Bosnian Muslim refugee children and some of their mums, when she’d only offered to take one.

Two at most, if they were siblings.

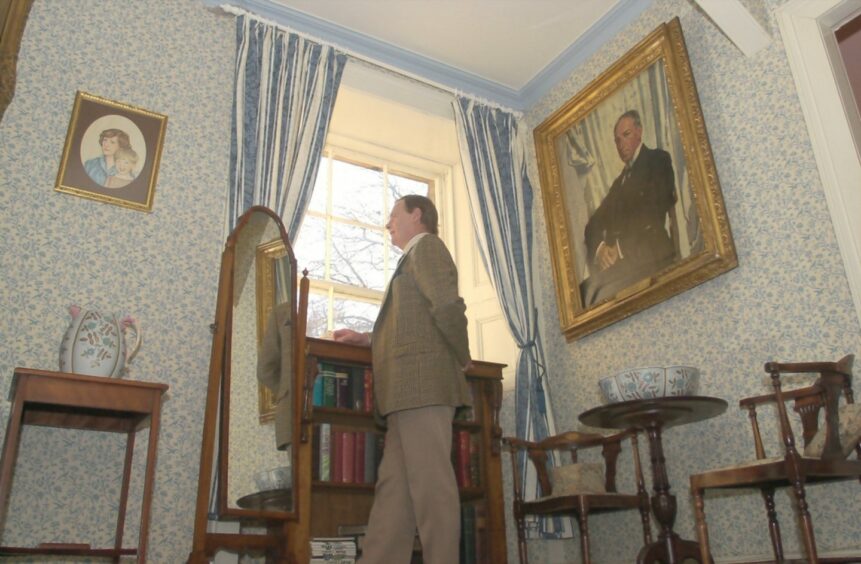

She and her late husband Andrew were living in Trochelhill farmhouse near Fochabers during the Balkan wars of 1992-96.

Andrew was the sales and marketing director for Donside Paper Mill in Aberdeen at the time, and had grown up at Trochelhill, a rambling old house with plenty of room.

Reports of the cruelty, torture and rape of civilians emerging from Bosnia at the time were horrific and hard to ignore, and especially offensive to someone like Clare.

‘Nothing clever about being lucky’

She grew up in a big house in North Devon, daughter of a baronet, spoiled rotten, she admits.

But her father refused to let her take her privilege for granted.

Clare said: “He taught me how to treat people with kindness and respect, and that there was nothing clever about being lucky.”

One Sunday in August 1992, she spotted an appeal for temporary foster homes for orphans from Bosnia.

It didn’t take long for her to persuade her husband around to the idea and together they began an intense journey filled with people who, Clare says, continue to add boundless love and happiness to her life.

It was all or nothing

She’s written it all down in All or Nothing, A Bosnian Odyssey, now published in various formats on Amazon.

Through the dodgy dealings of the charity organising the extraction of refugees, Trochelhill would six whirlwind weeks later find itself accommodating 21 highly traumatised children and four of their mums.

Clare wasn’t given the choice.

It was all or nothing, insisted the people trafficker.

Soon people from all over Moray heard what was happening and mobilised all their resources.

Generosity of Moray folk towards Bosnian refugees

They brought blankets, toys, books, videos, shoes and clothing, food, bedding, towels and toiletries.

Clare writes: “Local bakers brought loaves of bread, fishmongers brought fish fingers, butchers brought mince and a Baxter’s rep brought dozens of tins of soup.

“I have never seen anything like it and was incredibly moved by such generosity.”

The generosity persisted in every way imaginable while in the background Clare worked tirelessly to get family members out of Bosnia to reunite them with their loved ones at Trochelhill.

One of the best gifts came from nearby Gordonstoun school in the shape of Petra Lovrekovic, then 16, who came over to help translate the children’s stories.

Clare’s book contains many moving sections where she describes some of the horrors she found out through Petra that her new extended family had gone through.

“The horrors of what they had all lived through was something more terrible than any of us had imagined before these children had come to stay with us.

“It left both of us, Andrew and I, more determined than ever that we would do all we could to help them rebuild their lives.

“It also, of course, conjured up appalling pictures in our minds of things we had never dreamed could exist in Europe at the present time.

“A barbarity and cruelty, unmatched in Europe since the Nazis targeted the Jews in the Second World War.”

An illustration of how fragile the traumatised children were underneath their joyful play and fun at Trochelhill came when Buckie and District Pipe Band came to play for the children, resplendent in full regalia.

Clare says: “All was wonderfully well, until suddenly one or two whispered to each other, the laughter stopped, they backed away from the marching musicians, looking frightened and came nearer to the house and us adults.”

It turned out that the children had spotted the band’s skean dhus tucked into their woollen socks, and were terrified.

Later that evening, the full impact emerged, when David Mackay, tireless volunteer chef for the refugees, discovered all the kitchen knives where missing.

They were found stashed by the children in their improvised dormitories, under pillows and in shoes and clothing.

“It was clear that the deep fear which had shown so pitifully on the children’s faces whilst the Pipe Band had been marching up and down, had translated into an overwhelmingly urgent need to find some form of protection for themselves.

“And so they did, desperately trying to reassure themselves that they were indeed, safe.

“That they were so terrified made me feel sick, and at the same time awoke a new, far deeper level of protectiveness and commitment.”

Clare would end up successfully battling the establishment through politicians and courts to reunite the Bosnian families.

In the years since their Bosnian odyssey, Andrew has sadly died and Clare now lives in North Devon.

She’ll be returning to Trochelhill, now a guest house, on November 24 for a few days, and invites all her old friends from the time to join her there for a reunion.

She’ll also do a book signing in Elgin Library, details to be confirmed.

Many of the refugee families stayed here, around seven in Elgin, and one family went to London. One returned to Bosnia. Many of the children are now parents themselves.

Mark Pyper, headmaster at Gordonstoun School at the time, writes in his forward to Clare’s book: “This was essentially Clare Finlay’s work, her calling and her success, all accomplished without fanfare or fuss.

“She did not stop to ask, “Are these my neighbours and what can be done?’ She was clear, ‘These are my neighbours and I know what to do’.

“This book is in preparation in the early months of 2022 and Eastern Europe is again witnessing horrific scenes of deprivation and bloodshed.

“It is therefore not only timely but important that an account of what Clare Findlay achieved for a group of powerless refugees is fully told.”

Clare’s story recently appeared in the Saved By a Stranger series on BBC.

You might also like:

Conversation