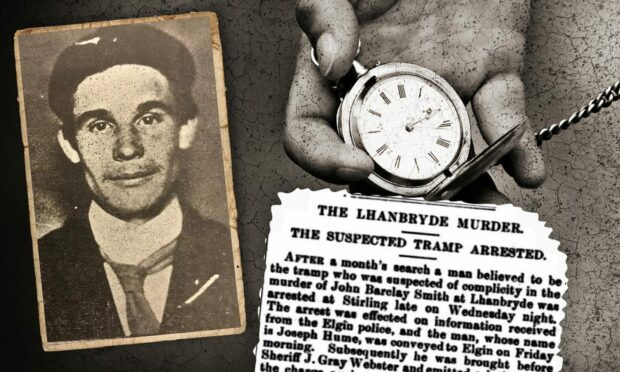

This is the tragic tale of two men bound together by poverty and an addiction to drink, in which one ended up murdered, the other hanged.

The murder took place in the Moray village of Lhanbryde, a few miles east of Elgin, in 1907.

The hanging of the perpetrator, Joseph Hume, took place in 1908, and was the last execution ever in Inverness prison.

All fingers pointed at Hume as the murderer, but he protested his innocence to the last.

How did circumstances conspire to bring about the double tragedy which made national news at the time?

Vulnerable victim in Lhanbryde murder

The victim, John Barclay Smith was a road contractor, almost 50 years old.

He had been married, with children, but due to his alcoholism, now lived alone.

He had spent most of 1907 knocking large rocks into smaller stones to metal the road through Lhanbryde and had been living in a couple of rented rooms in a cottage there.

Writer Dairmid Mogg has deeply researched John’s life and tells his story in the online magazine 1919.

He writes: “Any money he had went on drink. He owned almost nothing. The only things of value he possessed had belonged to his father, a mason who had died in 1901 — a 9lb mash hammer for breaking rocks and, fatefully, a silver pocket watch.”

‘The bothy mannie’

Everyone in Lhanbryde called John ‘the bothy mannie’, or just Bothy, after the cottage where he lived in squalor, mostly in the kitchen.

Dairmid writes: “There was an unused iron bedstead without a mattress, and another bed made of rough planks and posts nailed together, with a mattress of loose straw.

“There was a table and there was a crate that he used as a chair. The place always smelled.”

Normally, such a poor creature would never make it into the history books, but John had the misfortune to meet someone who seemed a kindred spirit, in terms of drink at least.

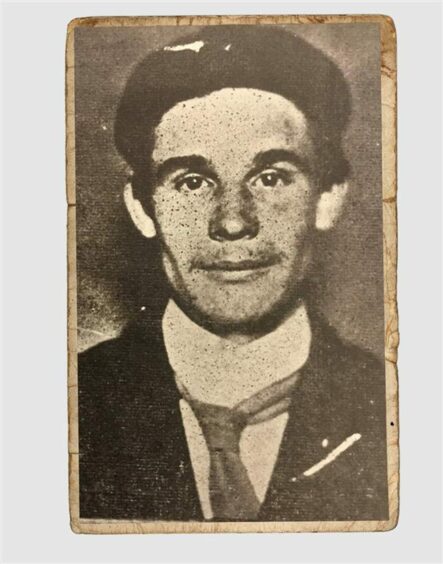

Joseph Hume came from the Borders, where his father was a stonemason. Instead of following in his footsteps Joseph joined the army – twice.

In 1906 he joined the Northumberland Fusiliers, but didn’t last long, deserting after four months, and then enlisting in the 2nd battalion of the Highland Light Infantry as Joseph Rutherford.

Arrested for desertion

He didn’t like it any better second time around, and was arrested twice for desertion that year.

The fine left him £8 in debt, the equivalent of £1,125 today.

He was ordered to pay it back to the government at one penny a day, taken directly from his army pay at Fort George near Inverness.

He deserted again, desperate to get to Edinburgh, but was penniless, so needed to take on some labouring work.

Thinking to dodge army pursuit, he headed towards Aberdeen and but had no luck trying to find work in Elgin three days later.

Then, most likely in a pub, he met a potential saviour in the form of John Barclay Smith.

Fateful kindness

Fatefully, John said he needed help breaking stones for the turnpike road, and offered Hume pay, food and lodging in his bothy.

The two embarked on a drinking spree for a couple of days before setting off to work on the rocks John had been contracted to break.

John used his father’s mash hammer, and borrowed one for Hume to use.

Hume barely broke a yard of rock, and did it badly.

Next day, Tuesday September 24 1907, was to be the last in the bothy mannie’s life.

They spent the day drinking

He and Hume ducked out of work after a short while and headed for Elgin to spend the day drinking.

It was late before they got back to the bothy, both very much the worse for drink.

John lay down to smoke his pipe on his bed, while Hume fried fish for their supper.

John fell sleep instantly, Hume’s cue.

Hammer blow

He picked up John’s mash hammer and brought it down twice on his head, before making off with anything of value he could find.

Ironically, while Hume was dirt poor, John was only one notch better off.

All he could find were a few coins, and John’s silver pocket watch, later to become a damning piece of evidence.

Fatal move after Lhanbryde murder

Hume made it to Edinburgh the next day, and in another fatal move, pawned the watch in Candlemaker Row to go drinking.

With his brother, and going under the name of Middleton, Hume left town.

His downfall came thanks to his army desertions.

Police spotted a description of a deserter in the Police Gazette, and put two and two together with the evidence they had from John’s murder in Lhanbryde.

A wanted poster went up and within two hours Hume was under arrest.

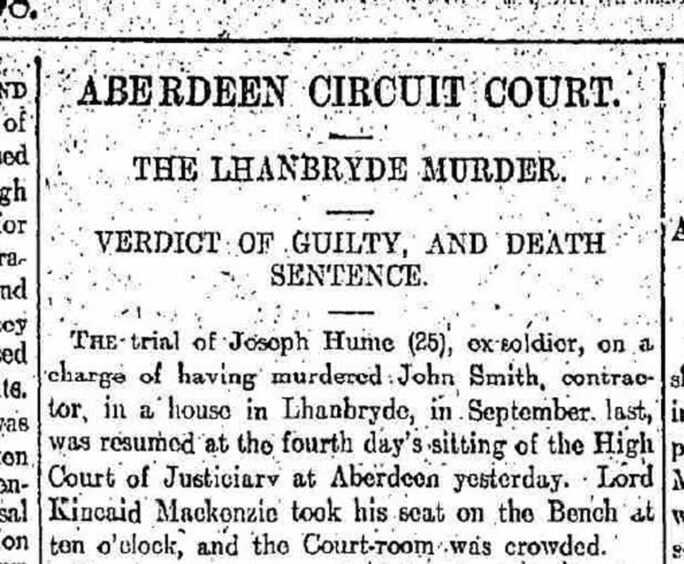

The trial, in Aberdeen, took four days; the jury’s deliberation only an hour.

Hume was found guilty and sentenced to death.

He denied knowing Smith, and knew nothing about how the pocket watch came to be in an Edinburgh pawnshop close to his brother’s house, at the same time as him.

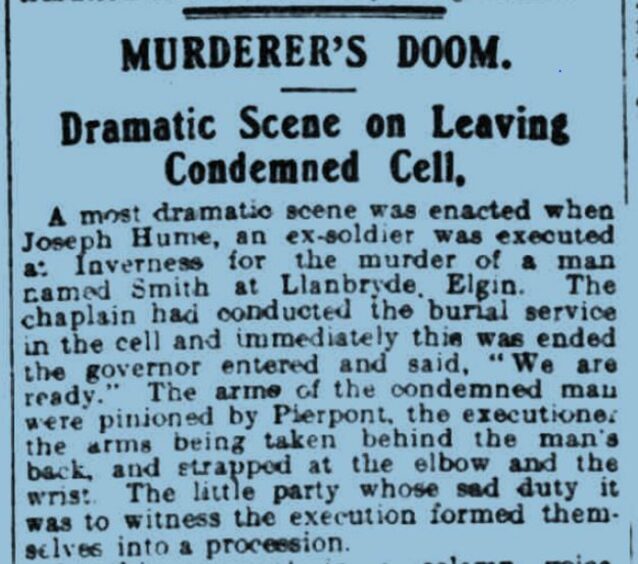

In fact he denied everything to the bitter end, even when the Inverness prison chaplain gave him the opportunity to confess in his cell, just before leaving for the scaffold.

The press reported: “In a firm voice, and with a look of earnestness, Hume replied, ‘I have nothing to confess.’

“As the white cap was being slipped over his head by the executioner from behind, Hume looking towards the chaplain with a piteous look on his face, said, ‘Good bye, father’ and then to the executioner he exclaimed ‘Don’t blindfold me, don’t blindfold me’. ”

He didn’t get his wish, as the hangman, Henry Pierrepoint (uncle to Albert, the famous last executioner in Britain) put the cap on him and released the lever.

Hume was buried in an unmarked grave within the prison.

He was the last person ever to be executed there.

Meanwhile John Barclay Smith had been buried before his family was traced.

A line mentioning him was later added to the Smith family gravestone in Banchory. His name sits under those of five of his siblings who had died before him.

Carved into the base of the stone are the words “Brief life is here our portion.”

More like this:

The Grantown Stabbing: Policeman killed by deranged Black Isle farmer

Conversation