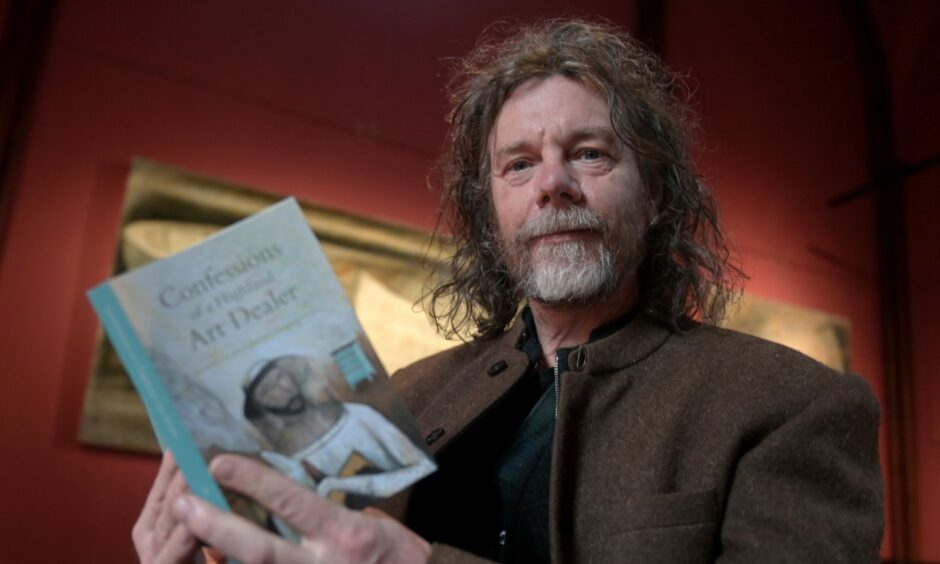

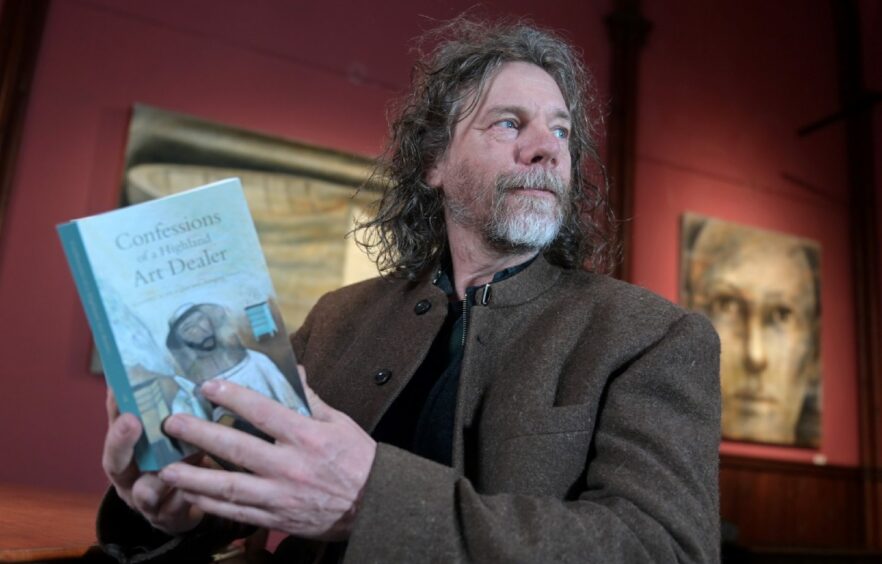

This year has seen a dramatic twist in the life of Highland art dealer Tony Davidson.

From almost three decades of discovering the talent in others, he has now discovered a hidden talent in himself, and a totally unexpected one.

Tony is well known in the art world for his Kilmorack Gallery near Beauly, an oasis where top Scottish artists exhibit their work, and a magnet for the rich to invest their excess cash.

But lately Tony’s become an author, and a recognised one.

His memoir Confessions of a Highland Art Dealer, published earlier this year, has gone straight into the longlist for The 2022 Highland Book Prize.

It tells the tale of a hot-headed 27-year-old who bought a derelict church on the fringe of Glen Affric in 1995, and through vision, obstinacy and determination, created a ground-breaking art gallery.

Rebellious behaviour

If writing wasn’t to the fore in Tony’s mind when he opened the gallery, why art?

He came top of sixth year in art at school before being ‘let go’ because of his rebellious behaviour.

After that came studies at the University of Edinburgh, perhaps a nod to those who wanted to see him treading a conventional career path.

Tony describes it as a ‘wild and crazy time’.

From it emerged a connection which would shape his destiny—the university crowd he hung out with were from Inverness.

From Edinburgh and St Andrews originally, Tony was drawn to the Highland crowd’s creativity and exuberance, and moved to Inverness.

His parents and siblings had no interest in art, but Tony felt at home amid the ceilidhs and smoky bars of the city.

A dramatic turning point would follow a few years later.

Tony bought the derelict church at Kilmorack, and armed only with a few quid and basic practical skills set about turning it into an art gallery.

He managed to get council planners round to his way of thinking, and from then on it was elbow grease, elbow grease, and more elbow grease.

And help from Black Allan, from whom he bought the church, and who continued to show up, wizard-like for the next few years to help solve problems.

Next, how do you set about populating your gallery with work by the best?

The visionaries who express their innermost thoughts, however disturbing, through canvas and paint?

Or in bronze, like the late sculptor and ground-breaking pop artist Gerald Laing, the former Army recruit who turned his back on all that to produce, among other things, breath-taking sculptures, selling for thousands?

Laing became a mentor for Tony, and remains one of the most important influences in his life.

He had a castle near Inverness at the time, and Tony had previously worked for him.

Laing agreed to lend the embryonic gallery three of his sculptures, and that kudos immediately put Kilmorack in the sights of serious buyers.

It’s not easy to track down the artists whose work you want in your gallery, as Tony describes in the book.

It’s not done to ask other galleries for their contact details, so you have to track them down yourself.

Then you have to go and visit them, a process which can sometimes takes months to complete.

Luckily, Tony relates the tale of many an artist visit in his memoir.

They’re fascinating and illuminating.

Allan MacDonald, a ‘walking palette….the blue fingerprints on his baseball cap were from loosely captured Hebridean skies and the white paint on his trainers came from foamy sea paintings.’

MacDonald prophesied that Tony wouldn’t last long in the art-selling game.

Kirstie Cohen, who lived close to the gallery, painting ‘romantic and sublime’ landscapes.

Exquisite botanical artist Elizabeth Cameron. Surrealist Michael Forbes. Best-selling James Hawkins.

Leonie Gibbs of Belladrum, also local.

Ceramacist Lotte Glob, whom Tony tracked down to the far north coast, and who has become one of Kilmorack’s steadfast exhibitors and supporters.

And sculptor Helen Denerley, whose threat: “You must do things right artistically, or I’ll whisk them [her sculptures] away”, earned her Tony’s appointment as the gallery’s ‘first official bully’.

And then came buyers, in the early years the lords and ladies of the area, seeming to buy the same thing every year, Tony says.

He had a spell of attending art fairs, but decided this was not his way of doing things.

Along came the internet and with it buyers from all over the world, while artists began to make their way to the gallery in the hope of an exhibition.

Prior to the crash of 2008, there was plenty of money swilling about seeking a home in art.

Things were looking good for Kilmorack.

But there was a large cloud on the horizon, not just the crash of 2008 which saw cash flow dry up.

The gallery is surrounded by nature such as many would give their eye-teeth to experience.

Living so close to it as to feel its presence very day, Tony is very attuned to it, so that when the slightest thing happens to disturb it, he feels an almost physical pain.

Landfill shock

When the millennium brought in Highland Council’s ‘Beauly Landfill Proposal’ it came as a complete shock.

“It was proposed that all of the waste from Highland Region and much of Moray’s old nappies, plastics and other waste too, should be dumped in the nearby quarry, making it the largest landfill in Scotland,” Tony writes.

The quarry had already swallowed thirteen hut circles, two chambered cairns and a Pictish carved stone, he notes.

Public anger

Public anger saw off that threat, but there were plenty more to come.

Nothing could be done to prevent the massive Beauly-Denny power line and its nearby base.

Its visual impact has been described as like someone taking a scalpel to a Rembrandt.

Ongoing, the massive expansion to the Beauly base, a 50 unit energy storage unit, further industrialising the bucolic landscape.

More and more windfarms

And deforestation.

Tony looked out one morning to see woodland in front of his home had suddenly disappeared.

Something similar happened to Helen Denerly too.

He said: “When the gallery first opened, it seemed like a big building, but now the timber lorries which pass are the same size as the gallery.

“Nature is being dwarfed.

“One man and a digger can now destroy huge amounts of everything in no time at all.”

But art can make a difference, he went on.

“Artists are all individuals doing things, very small and beautiful, and the ‘bad people’ are very ugly, doing things in concrete and steel.

“Even the solutions are windfarms made out of concrete and steel.

“Nobody’s grabbed the essence of what it’s about.

“Artists are the way to fight against it.”

In the closing of his book, Tony writes his apology to nature and his tribute to art.

“That is my confession, dear spring, dear forest and dear river. We didn’t mean to harm you. We just forget many things. And some of us, sometimes, remembered.”

As for writing, Tony wants to continue.

“I’ve got lots of ideas,” he said. “Perhaps too many.”

Conversation