A treasure trove of information about the lives of Norwegian children in exile in the Mearns during World War Two has come to light following a P&J article.

Drumtochty Castle near Laurencekirk was bought by the Norwegian government-in-exile during the war for use as a boarding school for traumatised young refugees from Nazi-occupied Norway.

A P&J article about Drumtochty was seen in Norway, and flushed out many leads and connections for Ragnhild Bie who has been researching life at the castle during the war for her MA thesis at the University of Agder.

The most significant lead came from descendants of the last Norwegian principal at Drumtochty, Jakob Rørvik, who saw the article and offered Ragnhild Jakob’s private archive from the time.

She said: “This archive is very exciting and wide spanning and includes everything from photos to letters between the pupils, the educational minister, and parents.

“It also helped me track down a handful of the pupils still alive today, so I was able to meet them and interview them.”

Traumatised

Drumtochty functioned as a boarding school from 1942-45, keeping alive Norway’s education and traditions ready for the day when the children could return home after the war.

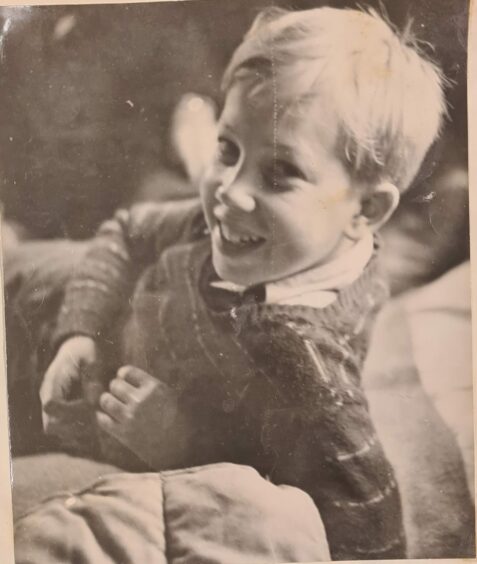

There were around 70 children, many of whom had gone through hell as refugees and exiles, and 30 staff members, some equally traumatised.

Jakob Rørvik, the third and last principal at Drumtochty, was already a teacher there before he became principal.

He created the archive himself and planned to write a book about it but sadly died before he was able to.

The archive contains about 100 letters from former pupils and staff, mostly written to Jakob in the 1980s, full of nostalgia and fond memories of their time at the castle.

There was also a film with wartime recordings from Drumtochty.

Ragnhild says it’s thought to be the oldest Norwegian documentary in colour.

A copy of a manuscript made by the Norwegian Minister of Education in exile, Nils Hjelmtveit also emerged, entitled in Norwegian “The fairytale of Drumtochty Castle. The Scottish Castle that became a school for Norwegian children in the years 1942-45.”

The archive also holds reports of the school council meetings, offering insights into the practical problems and challenges faced at Drumtochty.

The castle cost the Norwegian Government £5,500 (about £300,000 today) to buy and fit out as a school.

The spaciousness of the castle with its 60 acres of land was a big attraction to the Norwegian Government who wanted the children to have outdoor activities in a healthy environment.

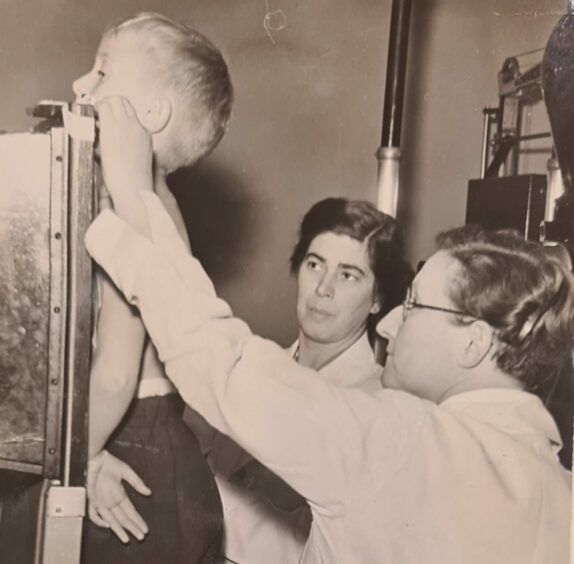

Many of the refugee pupils had originally been placed in crowded environments in big cities, and coming from rural Norway soon found themselves ill with diseases like tuberculosis.

Many of their parents, also traumatised from living under Nazi occupation and their arduous escapes to Britain, were reluctant to send their children away to boarding school, and needed considerable encouragement from the Norwegian government.

Eventually they arrived, coming from Glasgow, London, and Buckie, where there was another Norwegian contingent.

Fanfare

The castle was opened amid great fanfare by the exiled King Haakon VII on November 2 1942 with headlines at home trumpeting ‘the idyll at Drumtochty’.

There was a large helping of propaganda behind this, Ragnhild explains.

“The government wanted to portray the school as a peaceful, harmonic place for the children during the war.

“They speak nothing of the problems that occurred, like the TB infections, troubles with the staff or the pupils’ difficulties adapting to being away from their families during a time of crisis.”

But the fact that the government facilitated the documentary film found in Jakob’s archive shows they perceived the school as an important part of Norwegian school history and ought to be remembered, Ragnhild says.

The Drumtochty family

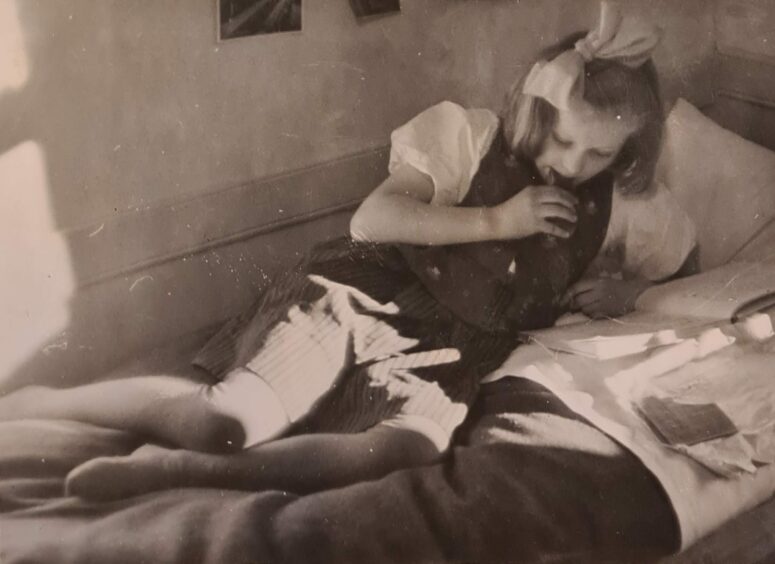

The principals and staff promoted the idea of the ‘Drumtochty family’ to create strong bonds within the little community.

It seems to have worked, as Ragnhild discovered from Jakob’s archive.

“After reading the letters, it’s evident that most of the pupils continued to stay in touch with some of the other pupils, at least occasionally. Only five didn’t.

“The years they shared at the castle seem to still bond the pupils together, with several of the pupils having Drumtochty and its inhabitants frequently in their thoughts.”

One pupil, originally housed in London, said: “If it were not for Drumtochty, I may have been dead.”

The family’s London accommodation was bombed days after she and her sister headed to the Mearns.

Fortunately her parents were not at home, but she and her sister would most likely have been.

In Drumtochty, they felt safe, spared from the attention of German bombers.

But the TB and misbehaviour among pupils caused problems, sometimes more than the staff could handle, so they wrote to the education minister Nils Hjelmtveit looking for guidance.

Jakob’s archive reveals the tight bond between the Norwegian government and the school, “with a feeling of kinship and a sense of openness between them that’s not normally to be taken for granted between a school and a ministerial department.”

Sex attack shock

The school community was rocked when a male pupil forced himself on one of the girls.

He was expelled immediately, and fearing more such incidents, staff convened to discuss whether all the oldest pupils should be sent home.

They decided all pupils had to quit school after Easter in the year they turned 15.

It’s not clear if that happened, and in the event the miscreant boy was reluctantly allowed back after two months under a strict regime, and after the intervention of Nils Hjelmtveit himself.

There were other more innocent pranks, including nightly turnip stealing raids and high jinks on the castle’s old and fragile roof.

And punishment lines were meted out after one incident during a snowy winter: “I shall not go skiing on the rhododendron”.

Discipline was so strict as to make life boring, but one former pupil says it was probably necessary.

Overall, the children’s health improved at Drumtochty.

They were fed well, had plenty of fresh air and got away from the terrors of the air raids.

But homesickness was the reality, as Ragnhild discovered through her research.

“With few exceptions the children did not have their family around, which left its mark on them.

“All the informants highlighted memories of the loneliness, emptiness and longing for their parents.”

It wasn’t all negative.

One of the pupils said that the most important thing he carried with him in his life after the war were the memories of Drumtochty, especially in the formation of his identity.

Another said that she had always felt different somehow after her attendance at Drumtochty, and there was something special about it.

Others felt that they would not have been the same people today, had it not been for Drumtochty, and one added that his stay at the castle provided him with a great interest in Scottish history.

“He also said that attending the school had made a direct impact on his professional life, as the advantage he got from learning the English language had helped him a great deal in his further studies,” Ragnhild said.

Ragnhild, who is the conservator/historian at D/S Hestmanden – Norwegian Warsailor’s Museum is continuing her research into the wartime experiences of exiled Norwegian children in Britain and is happy to hear from anyone with information to share.

She can be reached at Ragnhild.Bie@vestagdermuseet.no

More like this

How Drumtochty Castle became a safe haven and school for Norwegian children fleeing the Nazis