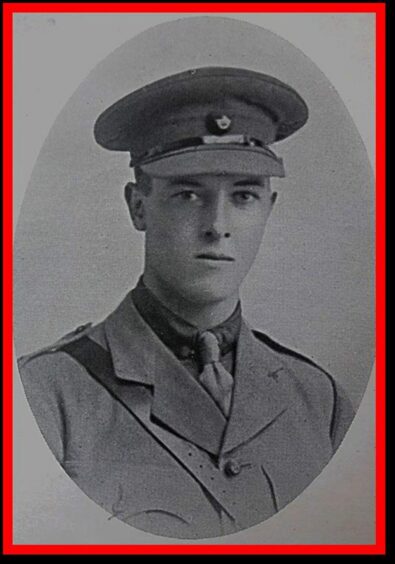

The moving story of a ‘young fermer’s loon fae Turra’ who died a hero in the First World War has obsessed a retired teacher from Aberdeenshire for the past 20 years.

Former Bridge of Don Academy teacher Colin Johnston from Peterculter first became aware of Lt John Low of Turriff when one of his pupils, Jane Discombe, came in with a bundle of his letters and other artefacts for Colin to look through.

Jane is John’s great-niece, and she told Colin that knowing his interest in the First World War, her mum Rachel thought he might be interested.

Colin read through the letters, was instantly hooked on John’s story, and decided to undertake as much detective work as possible to find out all he could about John and tie up some loose ends on behalf of his descendants.

Who was Turriff lad John Low?

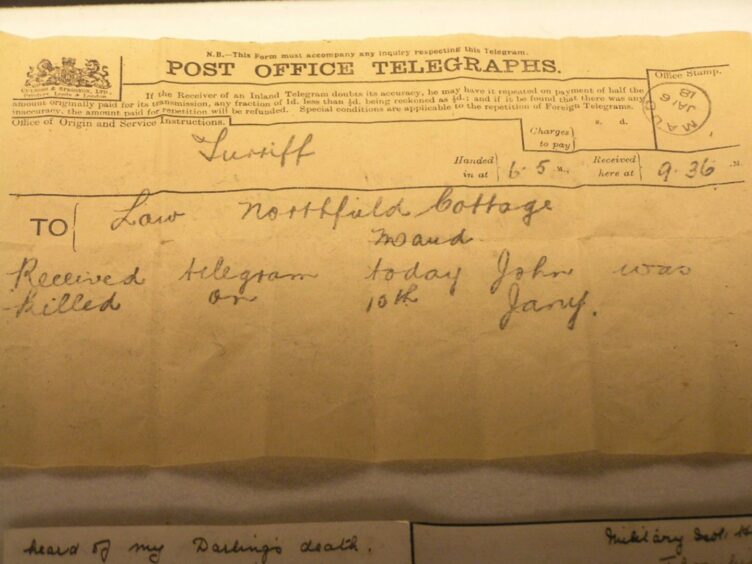

John was shot in cold blood trying to flush out German soldiers from a pillbox at Circus Point near Ypres on January 10 1918.

Yet he had no official grave, so where was he buried?

And what of his sweetheart Ada? The two had fallen passionately in love when Ada had nursed John back to health after a viral infection in an isolation hospital near Aldershot in 1917.

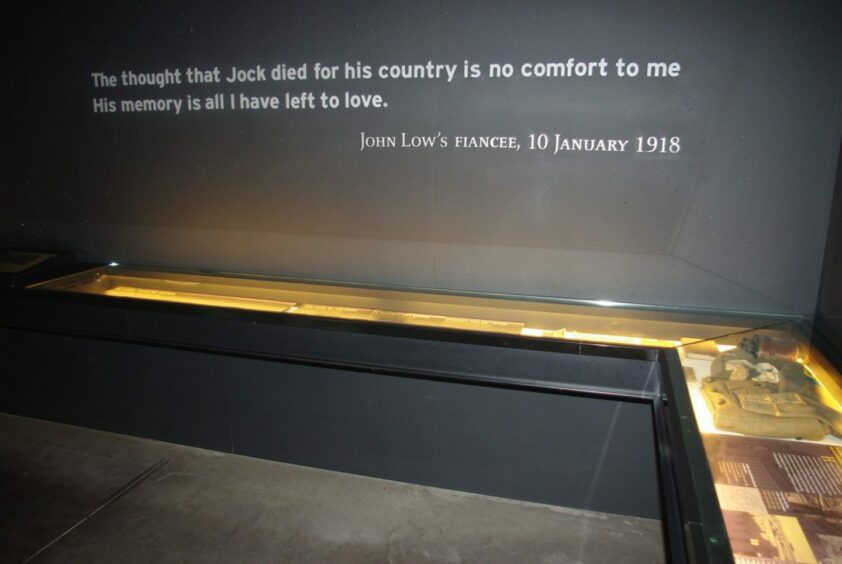

Heart-breaking words from her last letter to John’s sister are now reproduced for posterity on the wall of Tyne Cot cemetery visitor centre in Belgium.

“The thought that Jock died for his country is no comfort to me. His memory is all I have to love now.”

Colin painstakingly pieced together John’s story.

John Low was born in Turriff on November 1, 1894.

He was educated in Aberdeen and gained entrance to Robert Gordon’s Institute of Technology to study civil engineering, with an apprenticeship at Messrs. Walker and Duncan, Aberdeen.

Darkening skies over Europe

But events in Europe would soon take over, and late in autumn 1914 after seeing young men drilling and training at a local park in Aberdeen, he enlisted in 4th Gordon Highlanders, along with hundreds of others from the north-east.

There was basic training at the Gordon Highlanders’ barracks at Castlehill, followed by intensive training at Bedford Camp.

By early spring 1915, the Gordons were on their way to France.

Bagpipes at Le Havre

Colin said: “Many, if not most, of the men who sailed with John would never have seen the sea, let alone been on a large transport ship.

“Many spoke only the Gaelic.

“Others spoke Doric.

“However, when they docked at Le Havre, they were greeted by a tartan-clad band playing the pipes.”

But that joyful moment didn’t last long.

Off to Ypres

The men of Buchan, the Mearns, Formartine and Garioch immediately set off for Ypres, where they suffered heavy casualties in a diversionary attack.

It must have been a shock for John, for while he escaped unscathed, several of his friends perished.

Later in 1915, 51st Highland Division were transferred to a then little-known place called the Somme, soon to become the notorious killing fields of the war.

Colin said: “They were to take over positions previously held by men of 36th Ulster Division in Thiepval Wood.

“Early in 1916, the Scots practised time and again for the forthcoming ‘big push’ in the summer of that year.

Slaughter

“4th Gordons were not involved in the slaughter of the initial attack on July 1st, when 19,240 men of the British Army died.

“A few weeks later, however, they participated in the fruitless attack on High Wood in the southern sector of the Somme battlefield.

“John participated, but again was lucky enough to remain unscathed.”

In his off-duty moments, John faithfully communicated with his sister back home in Aberdeenshire.

Colin explained: “He would thank her for all sorts of gifts sent by his family, such as food, including sausages, and supplements to his uniform eg. extra socks and woollen gloves.

“He also asked for, and received, copies, in French, of The Three Musketeers and other French novels.”

By November 1916 4th Gordons moved to Mailly Wood ready to attack a highly defended German position near Beaumont-Hamel.

Tunnel system

After battle began, John entered a German defensive tunnel system some 50ft below ground, with four massive dug-outs designed to shelter 250 men during artillery shelling.

“He saw the destruction caused by the successful attacking troops,” Colin said, “and also some more surprising objects, including vast amounts of food, sausages, cakes etc, and equally vast amounts of alcohol, mostly beer, wine and schnapps.

“There were also amounts of women’s clothing and a grand piano.”

John’s artillery and leadership skills during the successful battle for Beaumont-Hamel came to the attention of senior officers, so he was sent back to Aldershot no longer a Gordon Highlander, but a Rifleman in the prestigious King’s Royal Rifle Corps (KRRC).

He was now Junior Officer-2nd Lieutenant John Low, KRRC.

Cupid intervened when John contracted a viral infection and was hospitalised nearby.

“There he was nursed back to health by a young Welsh girl called Ada,” Colin said.

Head over heels

“Except that she was from Swansea and had two brothers and three sisters, very little is known about Ada, except that she fell head-over-heels in love with John Low, and he with her.

“This is clearly indicated in John’s references to his ‘sweetheart’ in the letters to his sister, teaching in Maud Junior School.”

Cruelly torn apart

But as winter 1917 approached, John and Ada were cruelly torn apart, never to see each other again.

By becoming a Junior Officer, John had effectively signed his own death warrant.

He was sent back to the Western Front, where life expectancy for subalterns might only be a few days.

John’s last few hours

Thanks to help from the Royal Green Jackets (Rifles) Museum in Winchester, Colin been able to find an account of Lt Low’s last few hours on earth, written by one of his section who ended up right behind him.

It tells how, amid hellish scenes of destruction and chaos, John and another 2nd Lieutenant were ordered to prepare for a large-scale raid on an enemy machine-gun position known as Circus Point.

They had to crawl across No Man’s Land – some 500 yards wide, an eternity – to scope out the territory with sketches of the lie of the land, and maps pinpointing marshy areas, barbed wire and other obstacles.

White smocks for camouflage

It was January and there was a covering of snow, so the 90 men who went over the top to carry out the attack wore white smocks as camouflage.

Down came the rain, so the smocks were quickly cast off and buried.

They reached the enemy front line unnoticed and unscathed, so good was the planning.

John’s section moved towards a German pillbox, ready to flush out its occupants.

He successfully dispatched the guards, and entered the pillbox.

Colin takes up the story.

“2 Lt Low, taking in the scene revealed and with revolver in hand, gestured the survivors to surrender, saying ‘You won’t come out, won’t you!’

“They were his last words.

Shot as he turned

“Then, a Bavarian Sergeant Major, his left eye hanging on his cheek, said, in perfect English, ‘Look out sir, there’s another one behind you!’

“As John Low turned, the Sergeant Major shot him.”

At that moment John’s company realised German reinforcements were approaching and they had to turn back across No Man’s Land, leaving John’s body behind.

In a letter to John’s sister, Ada wrote: “The only comfort I have is to know that I made the last year of his life happy. They were almost his last words to me.

“I just lived for him, my love for him grew larger every day until I felt I must shout out and tell everybody.

“Tell your mother that her son’s memory is very sacred here.”

No grave

After years of research, Colin eventually established that John has no grave.

“His name is on the list of other missing soldiers from the King’s Royal Rifle Corps on the Wall to the Missing, at Tyne Cot cemetery near Zonnebeke in Belgium,” he said.

When Colin visited Zonnebeke museum with Rachel and Jane in 2008, the curators asked Rachel for permission to display some of John’s artefacts in the visitor centre beside Tyne Cot.

Colin said: “They are presented in glass cases, in an extremely effective and compassionate manner.”

He takes comfort in the fact that although John has no grave, his name is seen every day by visitors to Tyne Cot, and John and Ada’s memories are being kept alive for posterity despite the pitiless brutality of the Great War.

More like this:

Band of brothers: Tribute to Aberdeen family who lost five sons in World War One conflict

Conversation