January 1953 was unseasonably warm in the north-east, characterised by calm seas, blue skies and bright sunshine – there was no hint of the deadly Great Storm lurking around the corner.

Lulled into a false sense of security, the fierce tempest that tore into Aberdeenshire on January 31 caught everyone by surprise.

Back then, it was harder to predict the ferocity of storms, and forecasters relied on ships and aircraft crossing the Atlantic to relay information to weather stations.

‘A raging tide of terror’

The Press and Journal branded it “a weekend of terror”.

But it was so much worse than that – it was the most severe storm for 500 years.

The death and destruction which rained down on the length of Britain, was the worst peacetime disaster of the 20th century.

In Scotland 19 people were killed in the great storm, but the total across Britain was more than 300 as a North Sea storm surge flooded England’s low counties.

Gales laden with snow, howled for 17 hours on end, as the P&J reported on “a raging tide of terror”.

The report added: “Buildings were carried away, communications were cut off.

“Old and young fled in their nightclothes.

“Homes on the Banff coast were demolished. Great chunks were torn from roads.”

People who went to bed on January 30 were rudely awakened to a living nightmare the next day.

Landscapes looked very different as 125mph winds made light work of trees and buildings alike during the wee hours.

Crushed to death under fallen tree

The full force of the storm smashed the vulnerable communities perched along the exposed north Aberdeenshire coastline, taking lives with it, as it continued its path of ruination towards Aberdeen.

Amid the trail of detritus was tragedy.

Alister Duncan, 25, a young woodcutter at Forglen near Turriff, was returning to his parents’ home in Banff when he was crushed by a tree on Forglen Farm Road.

He was leaving work as the storm began to take hold, and colleagues begged him not to risk the motorcycle journey home.

An only son, he was determined to get back to his mum and dad, but was found dead underneath a beech tree – he had only travelled 500 yards.

Stanley Rothney, a young traffic constable in Banff, was given the sad task of informing the poor lad’s parents.

Speaking in 2013, Mr Rothney reflected upon the storm, and said: “It was a maelstrom and it all happened in minutes. You wouldn’t believe that water could have

such power.

“Whole forests were down, roads were blocked, we were virtually cut off from the outside world.”

Fisherman William Mitchell, of Pitullie near Fraserburgh, lost his life when a huge wave crashed him against the wall of a house.

He had gone out to tend to his boat which had washed up on rocks.

Further north, the storm claimed the life of Dingwall lorry driver Colin Dunbar.

The 41-year-old died in Inverness Infirmary after he was struck by a fallen tree while trying to clear another tree that had fallen in front of his lorry.

Cottages were swept into sea

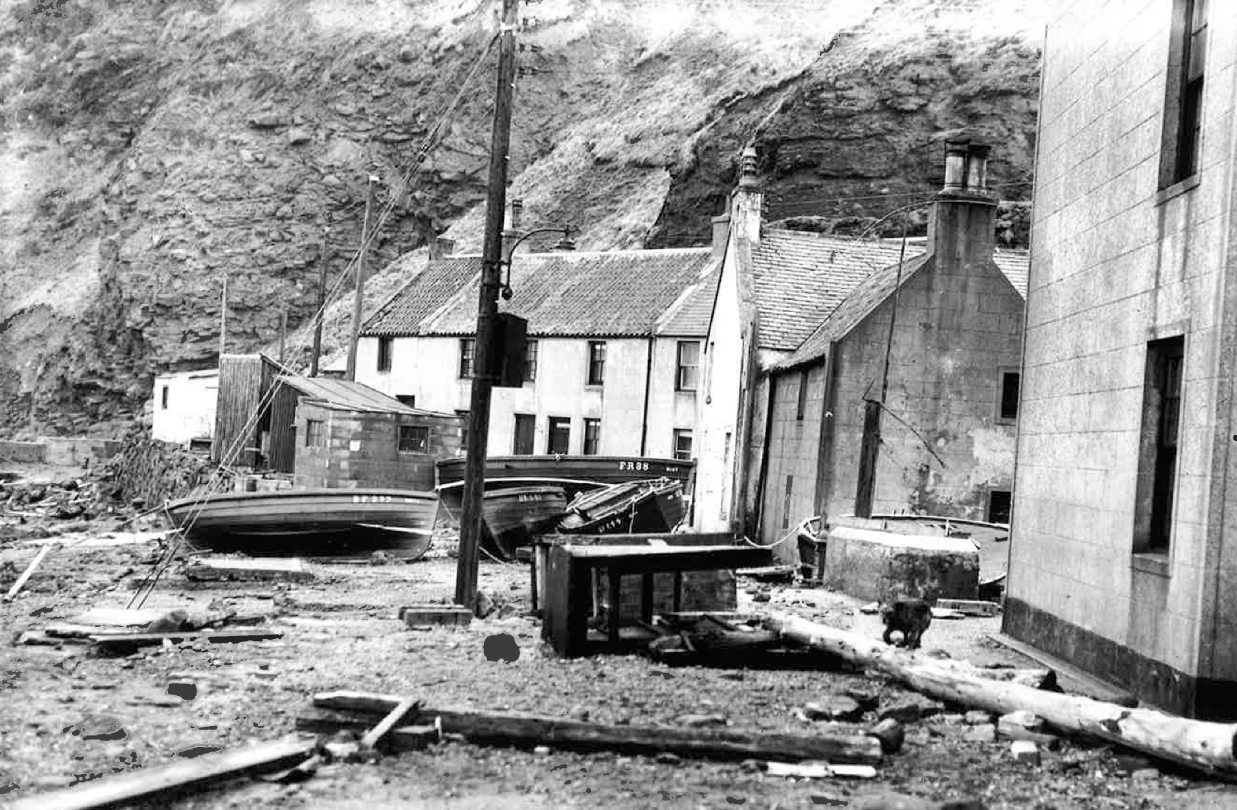

The ‘muckle blaw’ – a nickname that, if anything, downplayed the true devastation left in its wake – changed one little Banffshire village forever.

Crovie never really recovered from the great storm which ripped the heart out of the herring fishing community – both physically and metaphorically.

Like a line in the sand, generations of tradition was swept away within hours.

Even the cold, hard, granite was no match for the elements that thrashed the tiny village which clings onto the edge of Gamrie Bay.

Many of the picture-perfect seafront cottages huddled together – some gable-end to the sea, others face on – were swept away entirely and others were rendered uninhabitable.

In the local school log book, the headmaster recorded a “disaster” in Crovie and wrote that the waves were the “highest ever seen” and “many windows were broken and two houses disintegrated”.

Some locals were so heartbroken and fearful of it happening again, they simply walked away.

Many took up the offer of the sanctuary of a council house further up the hill in Gardenstown – it was said one man sold his house for a meagre £10.

In the months and years that followed, the ruined houses were bought by holidaymakers.

One of them was a teacher from Glasgow called Amy. She had grown up in Gardenstown and seized on the opportunity to buy number 48 Crovie after the storm – paying just £120.

Speaking in 1981, she said: “You could buy houses for Jeely jars after the storm.”

Blitz was ‘a picnic’ compared to storm

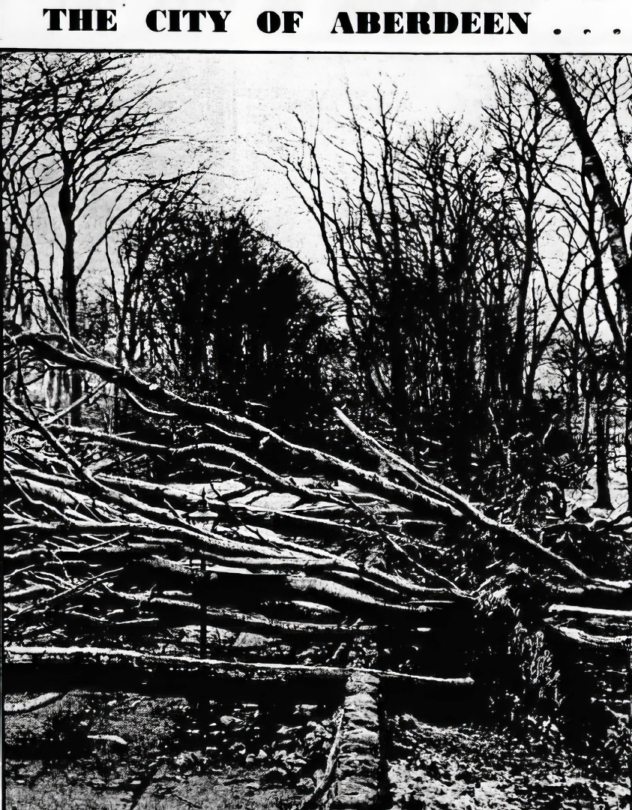

Aberdeen may not have borne the brunt of the storm, but the city did suffer too.

Around 4,500 trees fell, including a precious 100-year-old monkey puzzle tree at Hazlehead Park.

The power was out and there was a “rush on candles and paraffin lamps”.

The outpatients department at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary was swamped with people injured by falling branches.

And one of the most beautiful windows in St Machar’s Cathedral – showing the Nativity featuring depictions of Marischal College and King’s College – was blown out and destroyed.

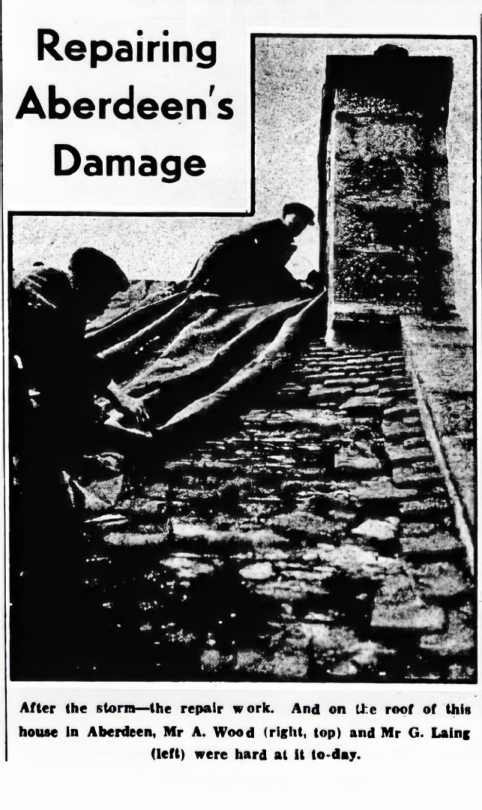

More than 200 reports were made to the council about roofs, hoardings and chimneys considered a danger to life.

Some residents had lucky escapes as chimneys crashed through roofs and slates were whipped off by the ferocious winds.

An Aberdeen slater said the wartime blitz was “a picnic” in comparison to the damage caused by the storm.

Electricians and communications workers worked day and night to win the battle of light and telephone lines, to reconnect “blacked-out” towns and villages.

In possibly the 1953 equivalent to losing internet connection, there was a desperate appeal for “tolerance” as Aberdonians complained furiously about losing their phone lines.

Petrified passengers had miraculous escape

And there was discord on the buses too.

The main Aberdeen to Inverness road was out of action for days. The woods at Pitcaple near Inverurie were among the worst affected, leaving logs strewn across the carriageway.

Petrified passengers on an Insch to Aberdeen bus trapped by fallen timber at Pitcaple had a miraculous escape as trees came down like “ninepins” around them.

Back roads were impassable too; a list of route updates provided to the Press and Journal declared the likelihood of reaching some destinations simply as ‘doubtful’.

Although some buses managed to zig-zag rural Aberdeenshire, passengers on cancelled services weren’t happy.

While the coastal communities were dealing with death and detritus, angry Aberdonians descended on the bus station.

Sitting alongside reports of citizens being sucked into the sea, was a news in brief about the harassed city bus inspector whose “left arm was sore lifting the telephone” to complaints.

The railways fared slightly better; lines blocked by trees were cleared quickly.

Men from lesser affected areas were drafted in to join clearance squads working tirelessly on the Deeside and Speyside lines to restore services.

Trees torn down like matchsticks

Elsewhere in Deeside, a woman was blown through a shop window in Ballater, escaping with cuts and bruises.

But the storm damage was obvious to see – great swathes of prime woodland around the Cairngorm foothills was flattened.

Trees were torn down with such ease they could have been matchsticks, and the equivalent of two years’ of tree felling was accomplished within hours.

And the loss of the woodland was felt keenly in the region – Deeside alone had already supplied half a million tonnes of timber for the war effort.

There was more wood than the sawmills could cope with.

And great estates renowned for their extensive and attractive policies were decimated.

Trees at Dunecht Estate were so badly hit that it was impossible to reach the house by the main road.

Ellon Castle and the Haddo Estate also saw their grounds changed beyond recognition.

The storm was estimated to have caused £40 million of damage across Britain – approximately £850m in today’s money.

A flood appeal fund was set up with match funding from the government, but no amount of money could replace the lives lost, or the communities changed forever.

Conversation