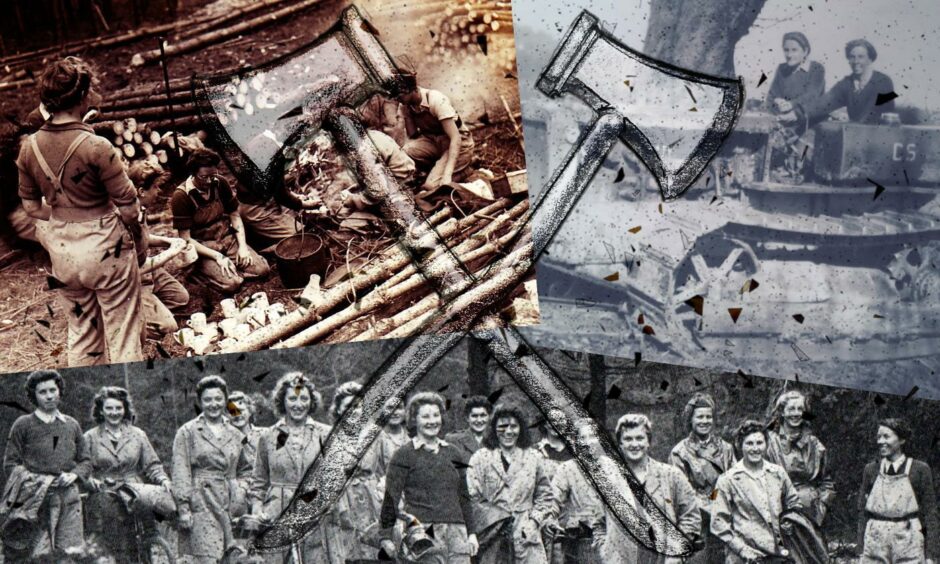

More than 80 years after the government appealed for women to volunteer to work in forestry for the war effort, they’re doing it again.

The surviving lumberjills from the 1940s could be forgiven a wry smile.

When they answered the call as young hairdressers, secretaries, or raw teenagers, they hadn’t a clue what hardships lay in store for them.

But their stoical, unflinching efforts made a massive and still largely unrecognised contribution to the war effort.

Today, the war is on climate change, and again, women are being asked to step up to fight it as lumberjills.

The Department of the Environment says there’s 100,000 shortfall in ‘green’ jobs to push Britain towards its goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, including planting 74,000 acres of woodland every year.

Modern lumberjills will find things very different from 80 years ago.

Today, the kit for the job will be good. Outdoor workers will have safety-conscious, warm, waterproof clothing for starters, proper training and state of the art equipment.

But in 1942 when the Scottish Women’s Timber Corps was founded, conditions for the women leaving home and hearth to do their bit for the war effort were very different.

Think rat-infested accommodation, revolting latrines, not enough food, freezing conditions, inadequate clothing and male scorn.

Yet for many it was an experience they would never forget, and counted among the best of their lives.

Lots of recruits came from the Highlands and north-east, or from further south to join up.

Their memories are captured in his memoir Timber! by Strathspey man Affleck Gray.

Born and brought up in Boat of Garten, Gray became a forestry officer, working all over the north.

When World War Two broke out he was seconded to the Ministry of Supply and became a strong supporter of the lumberjills and their input to the war effort, frequently coming into contact with them and noting their fortitude and skill.

Women like Chris Turner (nee MacDonald) of Inverness who with a colleague went along to the local recruiting office in Church Street after receiving call up papers for war service.

Both were qualified hairdressers and had hoped they might be able to continue as hairdressers in the WAAF (Women’s Auxiliary Air Force).

They were told that timber measurers were more urgently required in the clumsily named Ministry of Supply Home Grown Timber Production Department.

After some perfunctory training, the young women were taken to a wood some thirty miles from Inverness and told to thin certain trees.

It took a couple of weeks during which they were exhausted and continually hungry, but this was nothing to what lay ahead.

Their next job was away from home on the Achnacarry estate, seat of Cameron of Lochiel, and at the time a Commando training ground.

Chris told Affleck Gray the accommodation was a rat-infested bothy.

Filthy and unhygienic

“It was filthy and unhygienic beyond description.

“Sanitation was primitive, a filthy little shed in the yard without water and no place to have a bath or even a proper wash.

“We had to make do with an old zinc bath about two feet long and a foot wide, and some juggling.

“I used to sing as loudly as I could to frighten the rats off until my so-called ablutions were completed.”

Achnacarry was a tough shout too for Agnes Morrison, nee Small, who joined up in Inverness.

She told Affleck Gray she woke up in the disused cottage near the head of the Glen Mallie to find a hedgehog sharing her pillow.

“I suppose I could have had worse,” she said.

Chris Turner’s next job was at Contin near Dingwall.

No facilities

The accommodation, an empty cottage, had absolutely no facilities.

The latrines were unspeakable, the girls had to use upturned fruit crates for cupboards, and had to scrape mouse droppings off the butter at breakfast time.

Rationing was in force, and the women had to function on tiny portions of bread and oatmeal, with the occasional veggies, eggs or rabbit.

They were required to use their own clothes at first, soon wearing their soles paper thin as they tramped through the forest.

It would be 1943 before the emerging Women’s Timber Corp (WTC) would be supplied with uniforms: a green wool pullover, cord breeches, stockings, gumboots, dungarees, a hat and strong shoes for smarter wear.

Deirdre Mackenzie joined in 1942, thankful that she had been sent to the WTC rather than to work in a munitions factory, the other common, and highly dangerous, deployment for women during the war.

That winter was particularly harsh, the girls living in wooden huts and waking in the morning to find any hot water bottles which had fallen out during the night frozen solid.

She told Affleck Gray of the sadness she witnessed in one estate owner near Newtonmore when he had to watch his beloved trees being felled to turn into pit props.

“I remember him walking around his trees saying a last goodbye to them.”

Food was scarce and the work was hard, but Deirdre’s time in Speyside ended up changing her life completely.

The Canadian Forestry Corps had arrived to do their bit for the war effort, and the lumberjacks were soon squiring the lumberjills at dances, concerts and whist drives at the weekend.

Love struck

Deirdre fell in love with one particular lumberjack, and reader, she married him.

They went to live in Vancouver after the war, revisiting their old haunts in Speyside whenever they could.

Answering calls of nature could be awkward

When men were also working in the forest, answering calls of nature could prove a tad tricky.

Molly Hogg, working with the WTC in Finzean, Aberdeenshire recalled: ‘The men at Finzean had never had women working with them before so, but now something new had to be done for the girls.

“They decided to build a wee hut over a burn and building the hut on top of them.

“One of the men then said to an unsuspecting girl, named Clarisse, ‘Sit on this plank for a moment.’

“He took a pencil and drew round her bottom and cut to the shape.

“We did have a good laugh.”

But the men weren’t always so obliging.

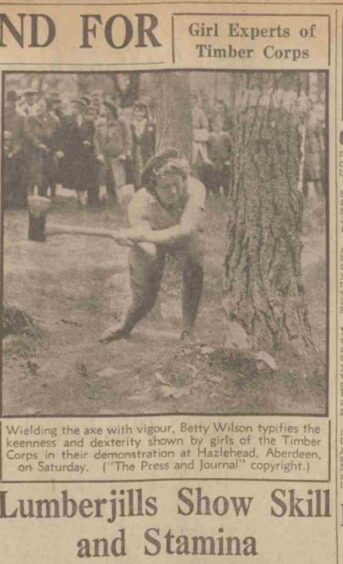

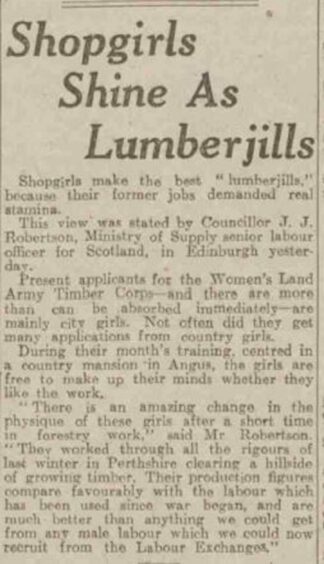

Affleck Gray writes: “At first they were treated with some derision and ribaldry by the male strength and were regarded as more ornamental than useful.

“Even the operations foreman held the same views as the men.

“I, however, with recollections of girl students in the Aberdeen University Mountaineering Club, with their ability to climb as sturdily as the boys and their capacity to portage heavy back-packs to a high-level camp, had other ideas and counselled a ‘wait and see policy’.

“ ‘Perhaps,’ I added, ‘you may be in for a big surprise.’

“How soon I was vindicated!”

‘Rough girls’ soon treated with respect

On another occasion, Gray, who was in charge of timber operations north of Dingwall arrived at a hotel with one group of girls where, upon asking for accommodation for the night, he was greeted with the reply, “How could I seat rough girls like that in my dining room with such as Admiral Dalton who is retired, but comes here every year for fishing?”

Gray was so angered by this that he refused to stay in the hotel but not before he had made sure the girls were given rooms and treated with respect.

More like this:

‘Some girls are jolly good fellers’: Women’s Timber Corps founded 80 years ago amid male scepticism

Conversation