Did you go climbing or walking in the mountains of Torridon in the late 60s and early 70s?

If you did, and you stayed at Glen Cottage Hostel, you would have experienced something fleeting and precious, although you might not have fully realised it then.

The first independent hostel in Scotland, Glen Cottage welcomed guests for a mere six years.

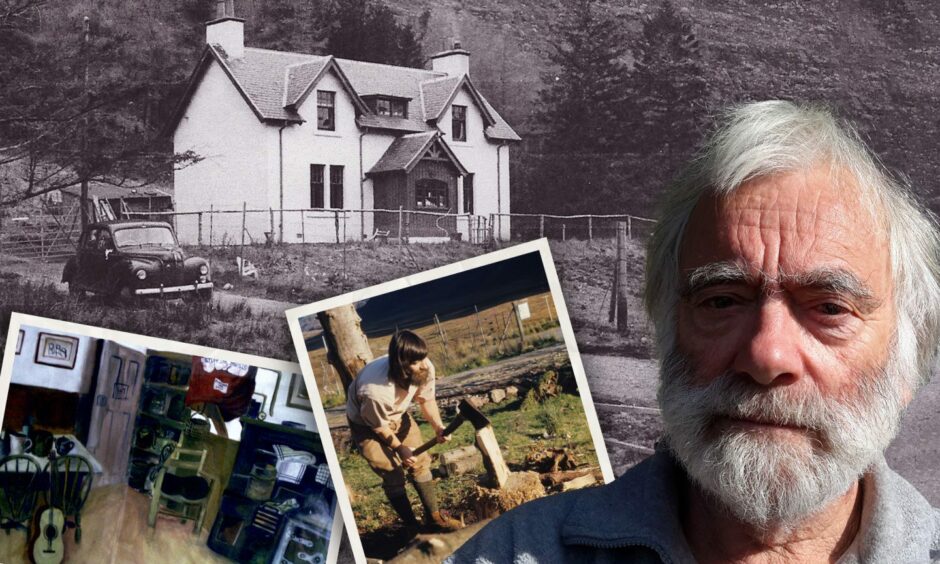

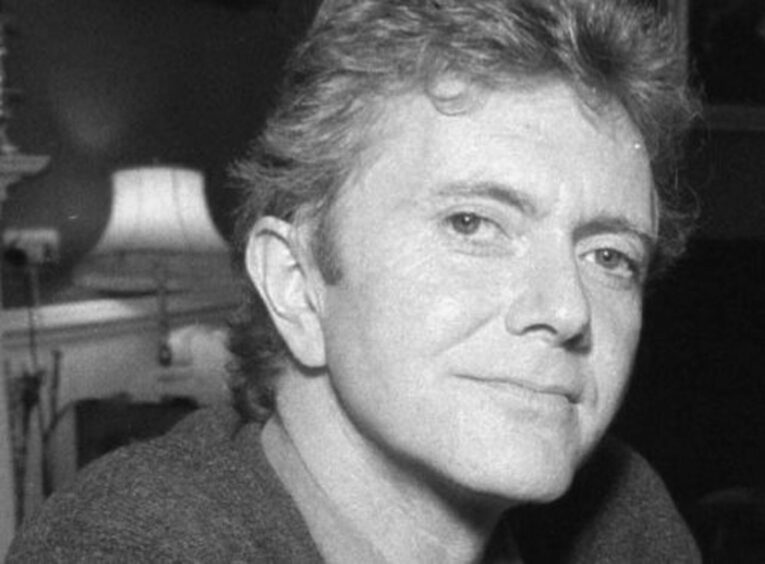

It was very much the personification of its creator, poet, musician, composer and master drystane dyker, Dave Goulder.

Dave had run Achnashellach Youth Hostel before that, but had become disillusioned by the restrictive dos and don’ts imposed then by the Scottish Youth Hostels Association.

He had a clear vision of how he wanted his ideal hostel, a relaxed environment where climbers, walkers, musicians and artists could congregate, have a drink or two and ceilidh the night away.

No membership ties, no rules or curfews, bring your own drink if you want to but don’t leave your common sense behind.

For those six special years, he and his then-wife, singer Liz Dyer, achieved just that at Glen Cottage.

They were already known to the folk scene through their participation in the folk music revival of the time, so it didn’t take long for musicians to find their way there, followed by their friends and fans.

Lure of the mountains

Climbers and walkers were already there for the calling, drawn to the breathtaking Torridon mountains.

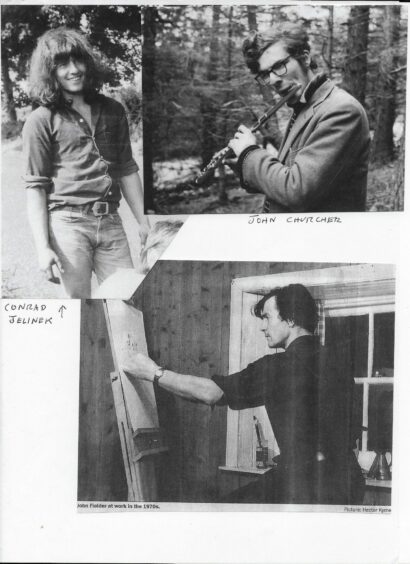

The roll call of visitors is a snapshot of the times, 1967 to 1973.

Aly Bain brought his fiddle; international climber and Ullapool GP Tom Patey brought his accordion and Chris Bonington; Chris brought Hamish MacInnes, and Hamish Brown mustered his lads to climb Torridon’s spectacular mountains.

Guitar royalty Davey Graham, composer William Sweeney and even the Magic Roundabout man Eric Thompson trod the floorboards.

“Young folk with little money learned from some of life’s best teachers,” Dave says.

“As one of them said fifty years later, ‘Glen Cottage needs a record. So many of us grew there’ ”.

Dave decided it was time to record it for posterity before the memories disappear forever into the mists over Ben Liathach.

The result is ‘A Torridon Portfolio. Rebel Hostel in the Glen, 1967-1973′, a memoir by Dave and many of the friends he made during those colourful years.

An early friend was Herbert Gatliff, instigator of a few private hostels in the Outer Hebrides, run by the Gatliff Trust.

He wrote to say he was fully behind what they were trying to do, and offered help in the form of some basic equipment, camp beds, gas cylinders, pain and manpower from volunteers working in the Hebrides.

Glen Cottage’s charm

Mary Scott, aged 16½, stayed in August 1968 and her diary entry perfectly sums up Glen Cottage’s charm.

“Susan and I arrived at Glen cottage about 3:30 PM.

“This hostel is a right scream! It is run by two folk singers, Dave and Liz. Dave has a beard.

“They have a super sense of humour.

“When we arrived there was this boy Simon (17½) making pancakes, so we had pancakes for tea!

“There’s a nice peat fire here and they grow their own peat.

“About 7pm there was a super sunset so we all piled outside to see a lovely bright pink sky.

“Then some boys invited Susan and me down to the Torridon pub.

“Arrived back at the hostel at 11 to discover a folk music evening going on, so we installed ourselves.

“We’d a midge death ceremony with fly spray and we were singing songs while watching the flies dropping off the ceiling. Went to bed at 1:15 am.

“Decided to stay at this hostel as long as possible.”

Nottinghamshire to the Highlands

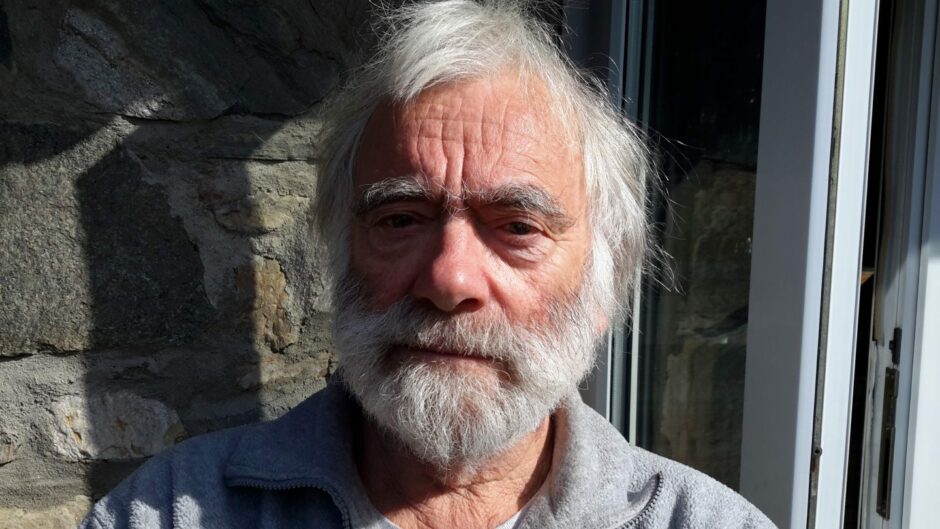

How did Dave, now 83, a farmer’s lad from Nottinghamshire, end up in the Highlands running a hostel at the heart of the hill-climbing and folk scene?

Life takes funny twists.

Dave’s dad came from a line of Derbyshire farmers and made the decision to keep farming in Nottinghamshire during the war as he was too old to be called up.

He took Dave with him as he went round the farms, ploughing and reaping and doing the jobs of those who were now serving in the war.

Dave’s mother died before he was four.

Bunking off school

“There was no one to make sure I got on the bus,” Dave said. “So I didn’t go, I took a left turn instead of a right and went down the fields, so my education at the end of it was somewhat lacking.”

He got work as a porter, then fireman on the railways and says it was there, aboard the steam trains with only the driver for company for eight hours, that he received his education.

“They unloaded all their enthusiasms and moans on the fireman, so I learned a lot on the footplate from the drivers.

“I learned about classical music, art, painting, literature.

Self-taught teachers

“These men had been born in the 19th century and they too were self-taught.

“One of them used to take me out rock climbing at the weekends on his old motorbike and I was just at the right age to absorb all this.

“I even read Gibbons’ Decline and Fall on the footplate between shovelfuls.

“I’d missed my education but I was certainly getting it now, I just couldn’t get enough, I got quite excited by every encounter and that set me up really well.”

Then Dave discovered vernacular folk music, and along with his passion for walking and camping the scene was set for his future.

After Beeching saw to it that the railways closed, Dave managed to get a job as the summer warden of Achnashellach hostel in 1961.

He ran it for four years, and says it completely changed him as a person.

“Suddenly I had a totally new environment where I was immediately home, but I had a lot to learn.

“Once again, with all these different people coming through and all their interests, knowledge and enthusiasms it was just carrying on where I left off on the railway.”

Dave had to tame and slow down his broad Nottinghamshire accent to make himself understood to foreigners.

Caught up in folk revival

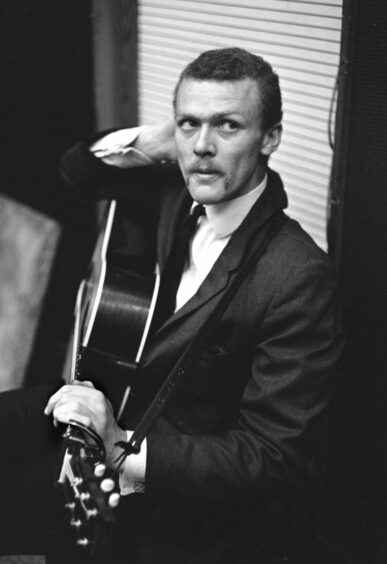

Meanwhile he taught himself classical guitar before becoming caught up in the folk revival of the time.

With two singers, two box players, one fiddle player and a piper in the nine-house township of Achnashellach at the time, Dave was in the right place for ceilidhs on Saturday nights with the likes of Jean Redpath and Owen Hand, established figures on the Scottish folk scene of the time.

But Dave’s views of how a hostel should be run got him sacked from his Achnshellach job.

He spotted an opportunity to try out his free-wheeling hostel ideas when the National Trust took over the Torridon estate.

“With another disgruntled warden, Bill Wallace from Glasgow, we discovered that the National Trust didn’t really know what to do with it.

“They offered us a six-year lease on Glen Cottage.

“It quickly became a magnet for musicians because by this time Liz and I had a reputation for traditional music, we’d been doing a lot of gigs, work on TV and radio, and I never failed to mention Glen Cottage at every opportunity.

Magnet for climbers and musicians

“All sorts of people turned up, Aly Bain, Davey Graham, the guitarist everyone copied, spent ten days with us.

“It was just that way, and we had the climbers as well.

“A lot of the climbers, like Tom Patey, played instruments as well.

“It had a reputation of being a good place to be.”

An example of happenstance which Dave loves to remember is how he met a couple he really took to, named John and Helen Kay.

Makar connection

They turned out to be the foster parents of Scotland’s Makar, Jackie Kay.

But all good things must come to an end, and once more it was Dave’s independent way of doing things that ended up in a fall-out with some of the stuffy members of the National Trust.

Another massive life change lay ahead.

Dave and Liz went their separate ways, while Dave took over a ruined croft house at Gairloch, and taught himself drystone walling as a way of doing it up.

The craft became another passion, and Dave gradually rose to the very top, eventually becoming an instructor to the Highlands and islands, travelling everywhere on his motorbike.

New hostel torched

But in 1977, his hard graft on his new hostel was undone when a jealous neighbour torched the cottage.

“It wiped out my past, photographs, the lot, gone,” says Dave.

Dave’s second wife Claire also left, and Dave had to rebuild his life from scratch.

Serendipity took him to Rosehall in Sutherland, where 40 years later he remains, with his wife of 28 years, Mary.

He found himself, and his various skills including hard-earned expertise in drains and septic tanks, welcome in the village and was able to earn a living walling and enjoy playing music with the Rosehall Ceilidh Band.

Dave’s song ‘January Man’ is his most famous, rendered by, among many others, Christy Moore.

But these days Dave has given up composing music, and turned to words.

He’s published A Torridon Portfolio. Rebel Hostel in the Glen, 1967-1973 under his own Drystone publishing company, and is watching and waiting to see how it’s received.

If it goes well, there might be a sequel, Dave says, with the emphasis on MIGHT.

“The book has more than twenty contributors, and their memories trigger off more of my own memories,” he says.

And as for drystane dyking, it’s on a temporary back burner.

As soon as Dave gets a new knee, he promises to be back on the job, never mind that he’s in his ninth decade.

More like this:

Archaeological dig reveals extent of historical illicit whisky production in Torridon

Conversation