One after another, as the names of the dead were confirmed, Aberdeen was shrouded in a veil of tears.

It wasn’t just the circumstances behind the River Dee ferry disaster on an April day in 1876 which chilled the blood, but the heart-breaking realisation that most of the 32 people who perished were children and teenagers.

There’s an old plaque on the Victoria bridge in Torry which highlights the bare details of the tragedy. But it doesn’t list the identities and ages of those whose lives were snuffed out on what should have been an occasion for revelry and fun.

According to the Aberdeen Journal, the first victim to be taken to the “deadhouse” was 17-year-old stonecutter Thomas Gowans. But soon enough, as “shrieks of distress spread across the area”, numerous residents had to arrange funerals for their bairns.

On April 12, the newspaper listed more than 20 of those who had walked on to the ferry and lost their lives.

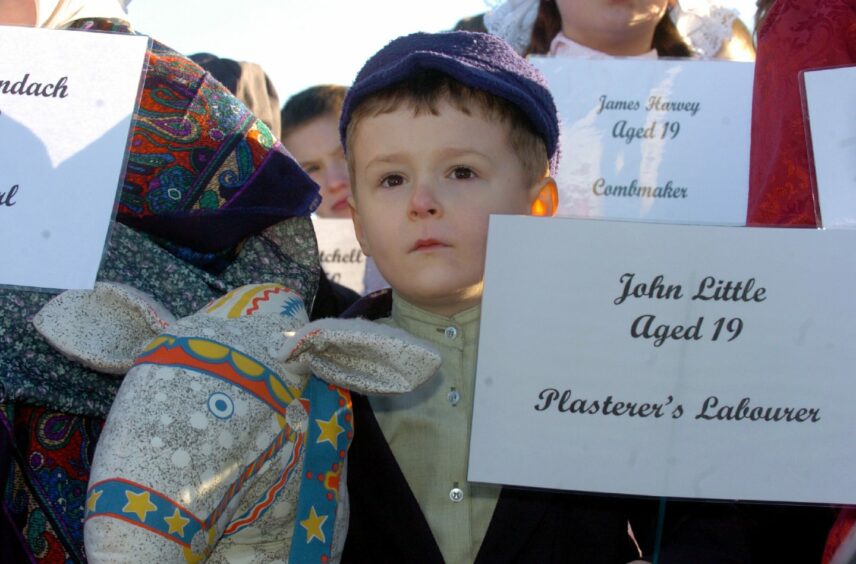

They were: William Robertson, aged nine; William Duncan, 10; Jessie McCondach, 13; Jane Cooper, 14; George McKilliam, 14; Robert Cay and Margaret Selbie, 15; John Hanson, James Smith and John Paul, 16; Andrew McKilliam, John Reid, George Young, James Slora, Alexander Smith and George Duncan, 17; James Leslie and George Burnett, 18; and John Little, James Harvey and William Shearer, 19.

A few moments of madness

Some of these youngsters were apprentices, trainee blacksmiths or labourers. Others, such as Jessie, was described as a “message girl”, while John Paul was a “newsboy”, George McKilliam was a “comb-maker” and Robert Cay harboured ambitions of becoming a lithographer. Alexander Smith, despite being “a deaf mute” was a cabinet-maker of rising repute among his peers. But all these dreams, all that promise and potential, was snatched away during a few moments of madness on the Dee.

Wednesday, April 5 was a Sacrament Fast Day in the city and the weather was fine, even though heavy snow had fallen a few days earlier. That encouraged many people to visit the fair in Torry and the Bay of Nigg and hundreds of them crossed the Dee by ferry with their mood described at the outset as “joyous” and “celebratory”.

After several days of rain, the river was swollen and fast flowing and the boat had already crossed a number of times before pandemonium erupted.

On its final journey, many of the throng pushed to get on board at the north bank. Policemen had been drafted in by Alexander Kennedy, the tacksman and leaseholder of the ferry route, because the day was expected to be busy.

They were present to help with the public, but their role did not include preventing overcrowding on the boat itself. This was agreed to be responsibility of the tacksman.

Prior to the fateful crossing, experienced sailor William Masson was worried about the speed of the current. He also raised concerns with Kennedy about overcrowding on the vessel, but the latter claimed not to have heard and so the numbers on the ferry were significantly over capacity.

Thereafter, whatever could go wrong did go wrong in a perfect storm of unintended consequences. The harassed Masson, who was regarded as a fastidious worker by his colleagues, went to fetch Kennedy a drink of water, but by his return, the boat was already on its way across the river. It was the only passage he missed that day.

A total of 76 people were on the ferry and it was obvious that was far too many as it began to list, moved mid-stream and advanced into the faster current.

Witnesses reported twice being asked to move around to counter the imbalance, but a fatal chain of events was unfolding. The wire became slack from the Torry side, then snapped altogether and that sparked the capsizing and a mass outbreak of panic.

Most victims were from Aberdeen

Some of the passengers were able to swim to safety. One woman was rescued by her husband who had launched from the shore because he was concerned about the state of the ferry and had voiced his concerns to others. A variety of small craft came to the aid of those in peril, but the larger ferry boats were too high on the beach to be any use.

The majority of the victims were from Aberdeen, ranging in age from nine to 50, while 44 others were rescued, but there was no disguising the unprecedented scale of the tragedy, nor the impact which it had on the city and those who lived and worked in Torry and prided themselves on being part of the ancient port’s rich history.

A public inquiry, the first of its kind in Scotland, was subsequently held in Aberdeen by the Board of Trade and was chaired by Captain Harris of the Royal Navy. It was well attended by members of the public. Witnesses reported that the river was flowing very fast, and that the wire-boat was more at risk than those being rowed across the water.

Mrs Jane Craig, one of the survivors, testified at the inquiry: “When I took my seat, there were only about 30 people on the boat. [John] Mitchell, the boatman, who was drowned, proposed to start [the journey] and he did start, but Alexander Kennedy, the tacksman, made him bring it back to fill it up.

“When the boat started the second time, I got a little frightened. The boat was overloaded, but it was not that which worried me so much as the wire.

“I had my creel on my back and, when I was thrown into the water, the rope of it round my neck nearly choked me. I managed to loosen it, but then I went down into the cold water. Thankfully, I was rescued by my husband [Torry fisherman Alexander] Craig.”

The inquiry ruled that a combination of overcrowding and poor quality wire had been the principal factors in the terrible events. But nobody was singled out for blame, even though much of the hearing cast a cloud over Kennedy’s conduct in refusing to let the vessel leave the quay until it had been packed like a sardine can.

A fund was set up to support those who had been affected with a substantial amount of money donated from subscriptions and private individuals. There had been plans for some time for a new bridge across to Torry, but the final impetus was provided by the disaster and Queen Victoria Bridge was formally opened on July 2 1881.

Conversation