The renowned Banchory-born fiddler James Scott Skinner took the art of fiddle music to new heights and became a worldwide superstar.

Skinner was born to be the greatest.

Becoming known as the Strathspey King, his talents as a composer were immense, writing around 600 jigs, reels, polkas and strathspeys in his prolific lifetime.

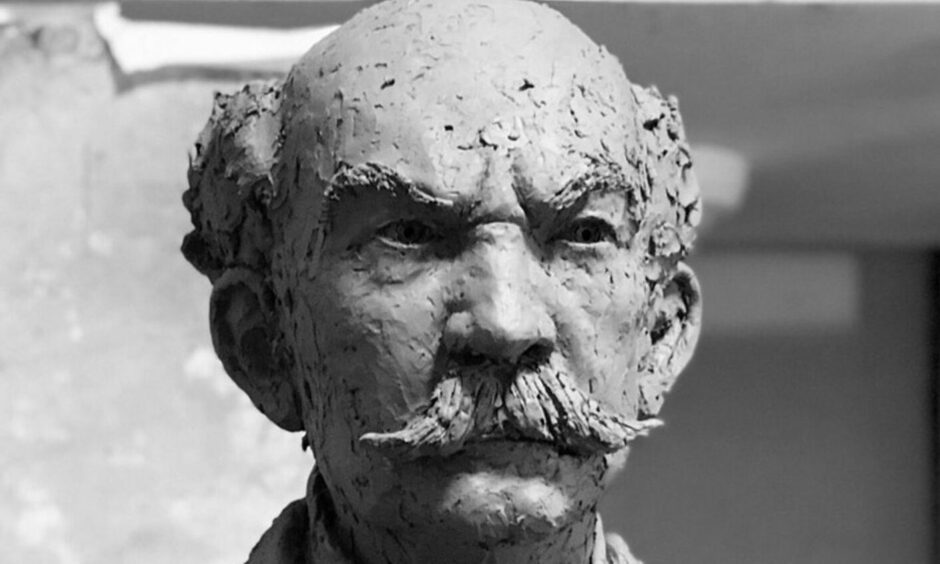

A major fundraising campaign has now been launched to raise funds for the erection of a life-size bronze statue in Banchory of Skinner who died aged 84 in 1927.

Fundraising concerts

A dedicated group of fiddle music enthusiasts, led by the Tarland Wizard Paul Anderson, has already raised sufficient support locally to commission leading Scottish sculptor, David Annand, to create a clay mould from which the bronze cast will be made.

“But we need to do much more to raise funds to take the project through to completion and we’re looking for the good people of Banchory and Deeside to rally round to commemorate the town’s most famous son as well as fiddle music enthusiasts from home and abroad,” said Paul.

Fundraising events in the pipeline include a charity dinner in Banchory and a star-studded concert which Paul is planning with fellow musicians in Aberdeen’s Music Hall.

Paul added: “The name of James Scott Skinner looms large in Scottish traditional music and arguably the Banchory-born musician is Scotland’s best known exponent and composer of fiddle music.

“His reputation is such that his music is still played all over the world almost 100 years since he passed away in Aberdeen in 1927.”

The members of the Strathspey King Memorial Fund have made a good start to the project and are delighted that Annand has agreed to mould the statue.

“David has a superb track record as a sculptor and has produced such well-known sculptures as the Alford Aberdeen-Angus bull, the Robert Fergusson statue in Edinburgh and the sculpture of Niel Gow in Birnam near Dunkeld,” said Paul.

“The statue of Skinner will eventually be erected in James Scott Skinner Square off Banchory High Street.”

James Scott Skinner statue could provide tourism boost

Banchory Museum is currently undergoing considerable refurbishment and Skinner will feature heavily in the exhibition to mark the refurbishment.

“We feel confident that with the reopening of the museum and with a fantastic new statue of Skinner nearby, the centre of Banchory will see a boost in visitors and that can only be good for local businesses,” said Paul.

Skinner was born in 1843 and his father William had been a fiddler for country dances.

He was just 18 months old when his father died, but his flair for music was nurtured by his older brother Sandy.

From Banchory School, little Jimmy went on to Aberdeen’s Connell School where one of the area’s leading fiddlers, the Tarland Minstrel Peter Milne, recognised his promise and offered expert tuition.

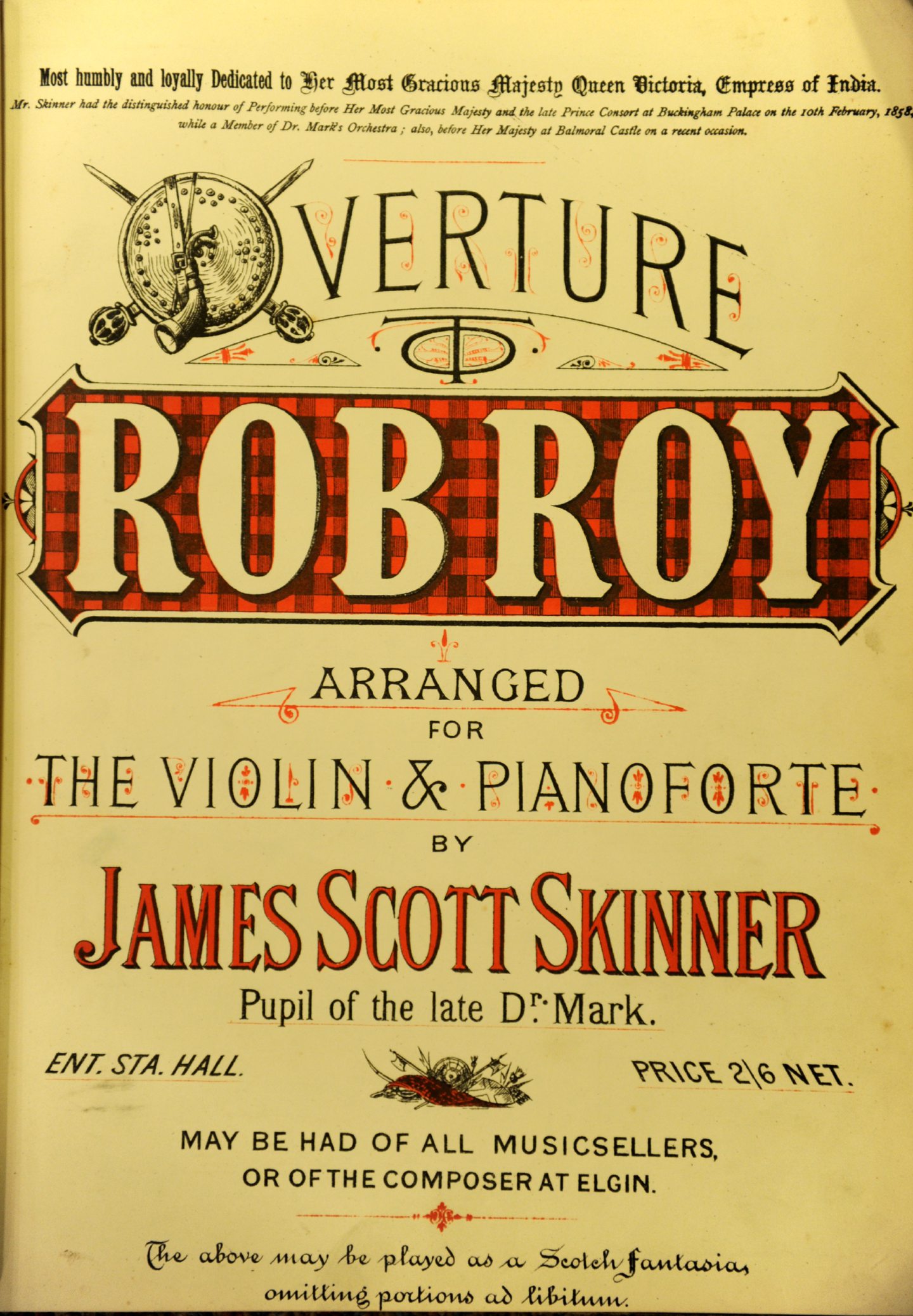

By 10, the youngster was recruited into the nationally-renowned junior orchestra Dr Mark’s Little Men, touring Britain and even playing before Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace.

Skinner attributed his own later success with meeting Charles Rougier, a French violinist with the Halle Orchestra, who taught him to read music.

In 1861 he returned to Aberdeen and took dancing lessons from William Scott.

At 19, Skinner took the Scottish music world by storm when winning a fiddling competition in Inverness, brilliantly outplaying the greatest stars of the day.

He also became a professional dancing master, basing himself in Strathdon.

Skinner gave dancing lessons to the children of Queen Victoria’s tenants at Balmoral and held dance classes up and down the country.

Recording career started in 1899

By the 1870s Skinner was traveling widely including the USA and Canada.

He was one of the very first Scottish artists to be recorded in 1899.

Skinner performed to huge audiences at major venues throughout his career including the Royal Albert Hall and the opening of the London Palladium in 1911.

During the First World War he supported the men who were fighting on the front line by touring north and south of the border at many fundraising concerts.

His recording career continued until 1922 and his music spread worldwide.

One of his best-loved single fiddle pieces remains The Bonnie Lass o’ Bon Accord.

The lass herself was city girl Mina Bell whom Skinner met at a party.

But, while his career flourished, Skinner’s private life was far from successful.

His first wife, Jane Stuart, of Speyside, died in an Elgin mental hospital. Their only child, Manson, was a talented Highland dancer.

But father and son clashed over almost everything.

Later, Skinner married Dr Gertrude Park and they lived together in Monikie before she ran away to Rhodesia leaving him big debts.

Money problems dogged him for much of his life, his wizardry on the violin not extending to his banking abilities.

He bought 25 Victoria Street in Aberdeen in 1922.

Tired of living in hotels and lodgings, it was the only property he ever owned.

In 1926 he returned to the US to take part in a fiddle competition.

Huge funeral for king of ceilidhs

Shortly before his death at 84 in 1927, Skinner told a friend: “When I am dead and gone, they will simply worship me.”

He was right.

Skinner would have been delighted with his huge funeral.

Intent on paying their last respects to the musician they adored, thousands of men, women and children lined up as the cortege moved slowly from Skinner’s home in Aberdeen’s Victoria Street, past Holburn Junction and on to Allenvale Cemetery.

His coffin was lowered into the grave to the music of Pipe Major George S McLennan, the greatest piper in the world at the time, and the chief mourner was Britain’s best-known and most successful music hall entertainer, Sir Harry Lauder.

It was a fitting end for the man who had entertained Queen Victoria, toured North America and was the first Scot to record music commercially.

In 1931, his old friend Sir Harry unveiled a memorial paid for by friends of the fiddler which featured a bust of the musician, a violin and the first few bars of The Bonnie Lass o’ Bon Accord.

Sir Harry’s graveside tribute summed up his friend’s genius.

He said: “There was music in every drop of Scott Skinner’s veins.”

Conversation