It was the worst peacetime shipping disaster since the Titanic.

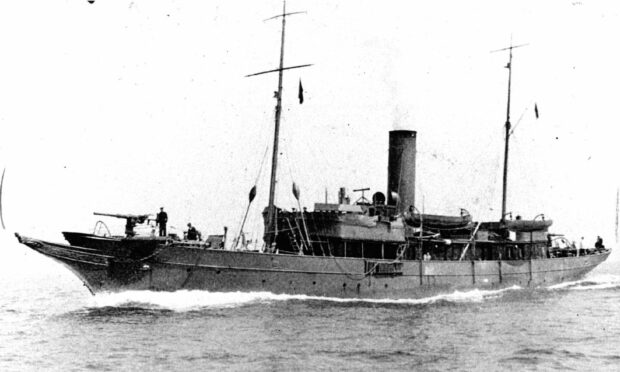

When the admiralty yacht, Iolaire, hit rocks a mile from Stornoway harbour and sank on New Year’s Day 1919, 205 men perished.

Celebrations to greet their homecoming from the First World War turned to an extended period of mourning as body upon body washed ashore.

The majority of the dead came from Lewis, 11 hailed from Harris and 31 were crew members from different parts of the UK.

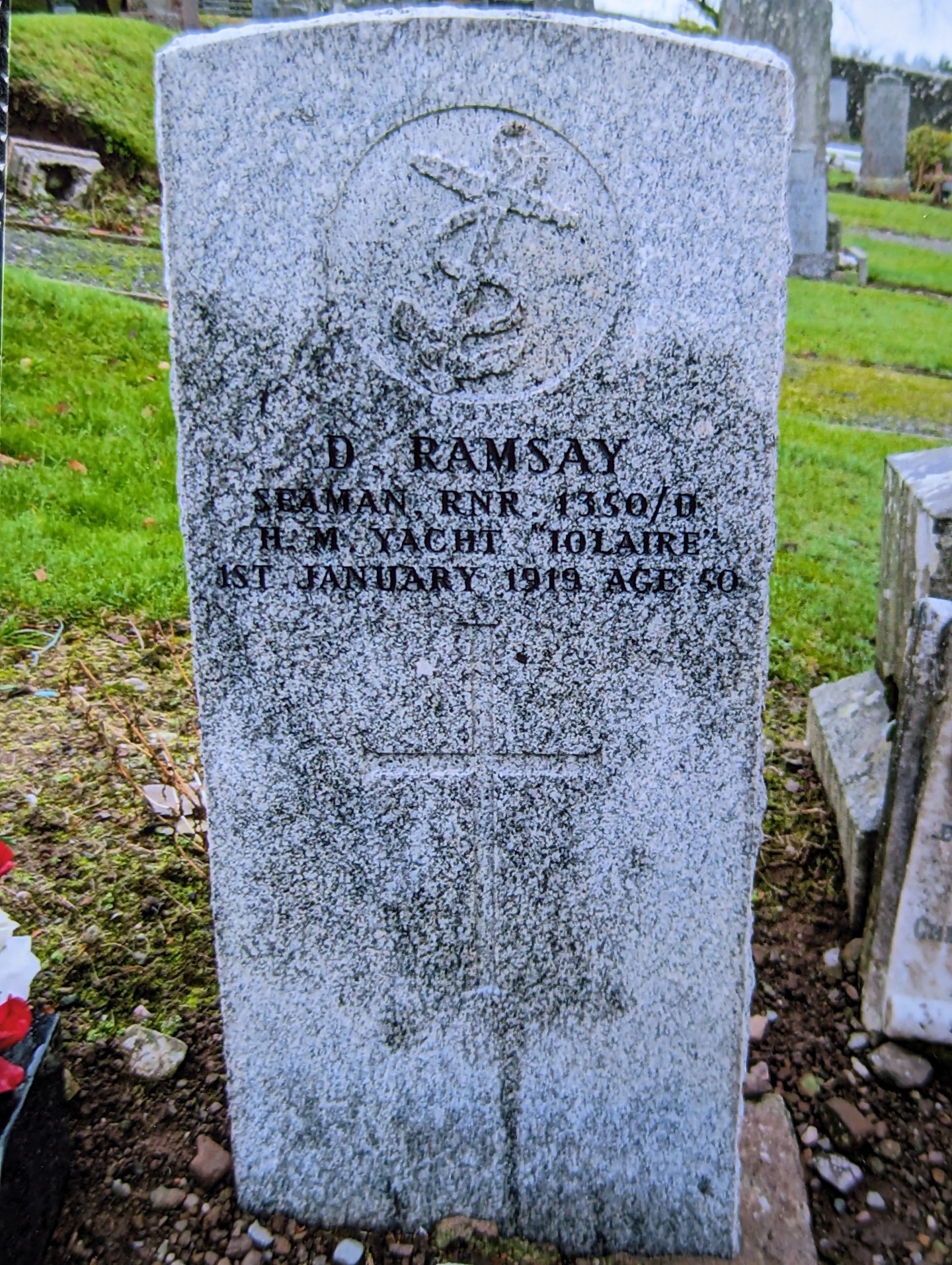

Among them was David Ramsay from Carnoustie.

His death left four children fatherless.

Some were luckier.

David McLean from Arbroath was chief motor mechanic on the Iolaire.

He was still on home leave in Glasgow when the yacht sank.

It was a sliding doors moment.

Who was David Ramsay?

David Bisset Ramsay was born on September 6 1868 in Westhaven.

Ramsay had long-term seafaring experience and was part of the unsuccessful Dundee Antarctic Expedition to find new southern hunting grounds on the Balaena in 1892.

Ramsay married Martha Robertson Buchan in 1907.

He served as a harpooner aboard the Arctic whaling vessel The Morning in 1910.

Ramsay, engaged in the whaling industry all his life, was called up to serve with the Royal Naval Reserve when war broke out and served on the store carrier RFA Intaba.

He served briefly on HMY Amalthaea with spells at HMS Victory, HMS Brilliant, HMS Zaria and HMS Kingfisher before returning to the Amalthea in October 1918.

Amalthea was now sailing under the name of HMY Iolaire.

In December 1918 Ramsay returned home for his Christmas leave to Auchterarder, where he lived with his wife and his four children.

He left on December 27 1918 to return to Stornoway.

The yacht set sail from Kyle of Lochalsh on the west Highlands mainland on New Year’s Eve 1918 for the Isle of Lewis.

As the lights of Stornoway came into view at 2.30am on New Year’s Day, the Iolaire hit the Beasts of Holm.

The rocky passage into Stornoway Harbour was poorly lit, and the ship suffered significant damage it could not recover from.

Distress flares were let off but no help came as the rockets were mistaken for fireworks celebrating the homecoming.

When the yacht sank, it killed 205 out of the 283 sailors onboard.

Almost the entirety of the Lewis’s young male population were killed in the disaster.

Some lives were saved

John Finlay MacLeod from Ness emerged as a hero in adversity.

The young man repeatedly swam ashore with a rope, oblivious to any concerns for his own welfare, and eventually helped to save the lives of 40 of those who were aboard the vessel.

The sailor and boatbuilder was rightly showered with awards and honours, although he shunned the limelight, prior to his death in 1978.

Indeed, his son heard him speak only twice about the Iolaire in the ensuing decades – once when war broke out again in 1939 and a quarter of a century later, when he finally returned along with an old friend to the scene of the Iolaire disaster.

His son, John Murdo, shared the story of his father’s courageous actions in an interview in 1969.

He said: “A flare went up and he identified the area.

“Having decided on his course of action, he gave the end of a heaving line to a fellow beside him and told him that he must not let it go.

“My father didn’t put the rope round his middle, but two times round his left hand and locked the end of the rope with his thumb.

“Then he dropped into the water. At the first attempt, the surge carried him away from the shore.”

After David Ramsay’s remains were recovered from the wreck he was returned to his home town and he was given a fitting send-off at Auchterarder Cemetery.

Ramsay’s coffin was draped in the Union flag, and carried by a bearer party of seamen and servicemen against the strains of a lone bugler playing the Last Post.

The Strathearn Herald reported: “Seaman Ramsay was a native of Carnoustie, and had been engaged in the whaling industry all his life till called up as an RNR man at the outbreak of war.

“Deceased, he was a keen freemason, leaves a widow and four young children.

“The funeral took place on Monday afternoon to Auchterarder Cemetery. A bearer party, consisting of two naval men and four sergeants of The Black Watch, carried the coffin, which was covered with the Union Jack, to the hearse.

“An escort party of volunteers, service men, both home and colonial, and returned prisoners of war, under the command of Lieutenant McBeth, preceded the hearse to the cemetery.”

For days after the disaster, the villages were under a dark cloud.

A naval court of inquiry was held in private but was inconclusive and did not apportion blame for the tragedy.

A later public inquiry criticised the ship’s officers for failing to reduce speed appropriately and failing to issue any orders after the collision.

There were also not enough life jackets or life-saving equipment on board.

A memorial was erected at Holm, near Stornoway, in 1958.

Centenary events in 2019

The centenary of the disaster was marked there in 2019, which was attended by Lord of the Isles Prince Charles and First Minister Nicola Sturgeon.

They both laid wreaths at the monument, which overlooks the scene of the tragedy, as did representatives from emergency services and other organisations.

A note left by Charles read: “In special remembrance of your service and sacrifice.”

A new sculpture to commemorate the Iolaire, adjacent to the memorial, featured a bronze depiction of a coiled heaving line, referencing the acts of John Finlay Macleod.

The Darkest Dawn tells the story of every man on board as well as the stories of those they left behind.

Co-author of the book Malcolm Macdonald said: “Around 250 children lost their father – eight children were born after their father died.

“Unlike the Titanic – where the victims came from all over the world – virtually all those that died came from the same place.

“The impact was unimaginable.”

Ramsay’s name can be found on the war memorial in Carnoustie.

Conversation