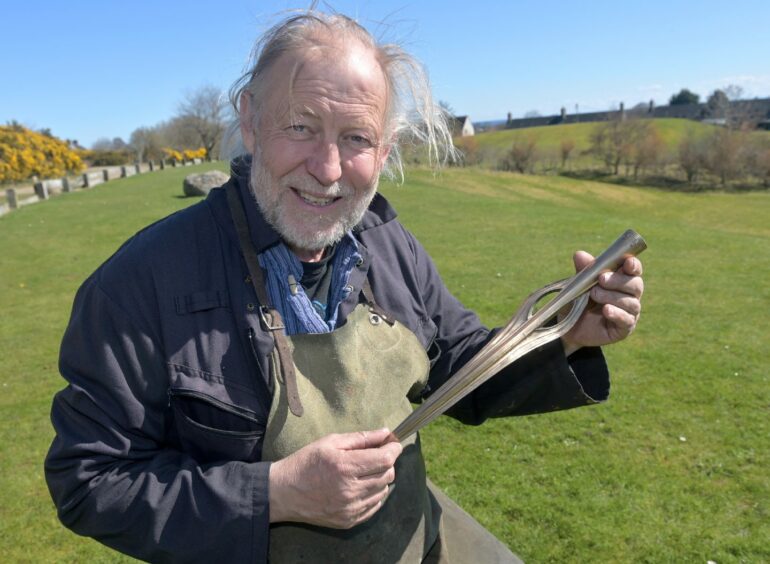

He calls himself ‘bronze swordsmith to the gods’.

Not sure about the gods, but Neil Burridge is certainly Britain’s top smith of Bronze Age tools and swords.

You can find his exquisitely crafted work in museums up and down the country, and it sells for a pretty penny.

I went to see him in action at Brora Heritage Centre doing a public demonstration of his magic.

He’s in demand all over the country for such events, so tours about in a small campervan, with a pigeon for company.

Pidgie is a 13 ¾ year old racing pigeon Neil rescued after finding her almost in shreds following a gruelling intercontinental race during which most of the pigeons died.

Today she tours with Neil, and in Brora can be seen plump and content sitting on eggs in a purpose-built cage in the van, keep a beady eye on proceedings.

Neil lays everything he needs for his art on the ground, and it doesn’t seem to amount to much.

A few sacks of charcoal, leather aprons and fire-proof gloves.

Goggles as a nod to 21st century health and safety.

Hinged wooden casts standing in fireproof boxes.

A small furnace, about the size of a large plant pot, a pair of skin bellows, tongs and a special implement to hold the crucible for tipping the molten metal into the cast.

The event is part of Clyne Heritage Society’s 25th anniversary celebrations, a two-month event which has included guided walks, talks, crafting, salt-making and flint-knapping.

Members of the public help build up the furnace by keeping it topped up with charcoal and working the bellows to build up and control the heat.

It takes time, so Neil has developed a unique brand of showmanship as a teller of tales and weaver of magic to keep visitors entertained.

Somehow it feels like he should be wearing a magician’s cloak and waving a wand.

You can imagine the same scene 3,000 years ago, perhaps with a little ritual dancing and chanting and a sorcerer’s apprentice working the crowds in flickering firelight.

That’s probably too fanciful.

Secret art

The alchemy of melting metal and casting it in clay was so skilled that the few who mastered it most likely practiced their art in secret.

The best recipe for a bronze sword is a 12% tin/copper alloy, a blade no longer than 26 inches at which it would weigh around 1 ½ lb.

The hardening process is what gives the sword its sharpness, so the cast is crucial, forging the edges down into a thin hard wafer.

Neil has perfected his techniques over the 25 years he’s been practising his art.

He says turning the all-important cast might take many days and castings until he is satisfied.

There’s plenty of scope for things to go wrong in bronze-smithing, molten metal and clay casts being a potentially explosive combination, so Neil uses wooden casts for his public displays.

Red hot furnace

The charcoal is red-hot around the crucible Neil has placed in it.

The crucible itself is made of dense, thick stone and small enough that you could hold it in one (strong) hand.

A 2ft sword will come from this eventually —it’s hard even to imagine how at this stage.

Now the heat is approaching 1000 degrees, and some nifty bellows work must lift it to 1190, and keep it there for 25 minutes.

Brora heritage officer Jason Randell is tasked with manipulating the bellows in a hypnotic, up-down rhythm.

It’s time, Neil decides. He needs volunteers.

He asks Natalie Davies and Iain Gosling who have come all the way from Portgordon in Moray to watch Neil at work.

Dream come true

For Natalie, a follower of Neil’s for many years and owner of a couple of his swords, coming to see him at work is a dream come true.

She and Iain are tasked with pouring the hot metal into the cast.

Neil gives them training.

He will command “Pourers to the bar!” at which they must lift the pouring implement in front of the waiting cast.

Neil will extract the crucible and set it into the implement at which the pourers must gently and smoothly pour the molten metal into a small hole in the cast.

They practice several times before Neil is confident they can handle the responsibility.

The cast flames as they pour in the red-hot lava.

There’s a surprisingly short cooling period before the metal has hardened and the cast can be opened.

And there it is, one bronze sword, a direct link back to our ancient ancestors.

Natalie brushes debris off the sword and holds it up.

It’ll take some polishing before it reaches the artistry of a finished piece, but it’s still a magical moment.

Neil is an extraordinary font of knowledge about everything to do with bronze making from geology to mythology.

It’s hard to find out much about him, though.

He’s originally from London, but now lives in Cornwall near a mined-out seam of tin.

He was in the landscaping business for years —”I mowed Richard Attenborough’s lawn” is all he’ll say about that—before making the break into bronze a quarter of a century ago.

There’s little he doesn’t know about his chosen craft, the science and art of it, its place in mythology and sacred texts.

A day with Neil is akin to time travel and a history of humanity.

There’s much to take from it, quite apart from his knowledge of geology and metallurgy.

I’m struck by his insight into the dark side of man.

“Powerful men would be tasking their smiths to make them a sword, and then would discover the next door leader’s smith had made him a slightly longer one.

“So they’d ask their smith for one even longer, and so on.

“It was the original arms race,” he says.

Conversation