Gayle visits the Peel Ring of Lumphanan – the remains of a 13th Century motte and bailey castle, with links to Macbeth.

It’s a bizarre sight – a flat-topped grassy mound encircled by an earthen bank in the middle of rolling Aberdeenshire countryside.

Dating back to the early 13th Century, it once boasted a timber castle on top, while a moat surrounded the base.

This enchanting spot – the curiously named Peel Ring of Lumphanan – is a place I apparently visited with my parents many moons ago, but I have no memory of doing so.

Also known as the Peel Bog of Lumphanan, there are few remains to be seen today beyond the motte, or mound, and substantial earthwork defences.

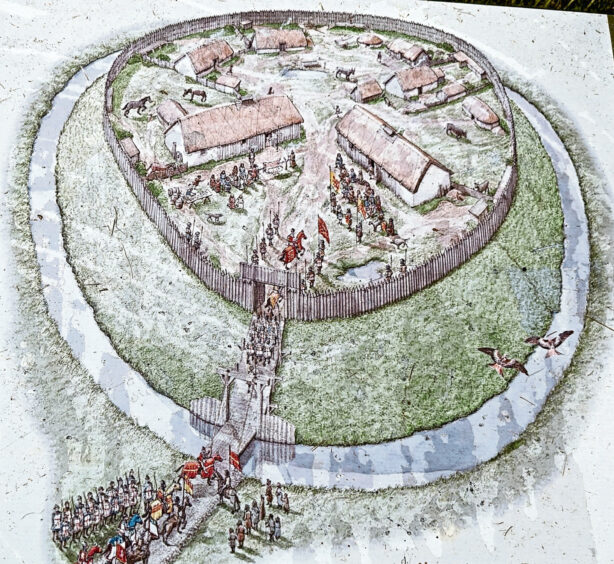

However, a sketch at the entrance to the structure imagines a community once bustling with people, buildings and livestock.

A drawbridge over the moat offered access to the castle, with water in the ditch controlled by a sluice system – now vanished.

You can visit the Peel at any time, but right now, with summer just round the corner, is ideal as the ground, which can be boggy, is about as dry as it gets.

Parking is free, and as I got out of my car, the first thing I spotted was a notice promising an “interactive historical journey” of the site via the Discover Deeside app.

Sadly, neither my phone nor my companion’s would download this when we visited. Maybe next time.

What is the Peel?

So, what on Earth is the Peel? And why was it called the Peel? Could it be because it boasts two concentric ditches that rather resemble an orange peel when viewed from above?

It appears, on Googling, that “peel” is from a word describing the way in which the structure was built – as an earthwork with a timber palisade, or palacium, in Latin.

An information board reveals that the “natural mound” was fortified around 1250, and established as the castle of the De Lundins, a Norman family that had acquired a large estate between the rivers Don and Dee around 1228.

The De Lundins were apparently known as the Durwards, or “door wards” to the king – more or less glorified ushers.

The castle featured briefly during the Wars of Independence in 1296, when Edward I of England invaded Scotland.

He rocked up at Lumphanan Peel on July 21 that year to receive the pledge of the Scottish lord Sir John de Melville, Lord of Raith. Melville submitted, and the castle was abandoned soon after.

Ha’ton House

What’s also known is that the mound was reoccupied in the 1480s when Thomas Charteris, of Kinfauns in Perthshire, built a two-storey property on the summit.

Known as Ha’ton House, it was demolished in the 1780s, but the foundations remain.

It’s a short climb to the top of the Peel, but the views, of hills, woods, and surrounding farmland, are stupendous.

Looking down on to a flat basin, you can see the layout of an old curling pond used in the 19th Century by villagers, which is rather fascinating.

Once I’d walked round the circumference of the Peel – and hopped over the remains of a ditch, getting slightly wet feet in the process – I set about looking for the Macbeth stuff I’d read about earlier.

Macbeth connections

Lumphanan has strong connections with the famous King of Scots, who ruled from 1040 to 1057.

When the Peel was taken into state care 900 years after Macbeth’s death, it was believed to be the king’s fortress… until later excavations revealed it was built some 200 years after his demise.

However, it’s claimed that Macbeth WAS killed here at Lumphanan, and not at Dunsinane in Perthshire, as Shakespeare would have us believe.

Within just a few miles of the Peel are three sites associated with his final battle.

Macbeth’s Stone, around 300m west of the Peel, is said to mark the spot where Macbeth was mortally wounded and beheaded by the future King Malcolm III in the Battle of Lumphanan, on August 10 1057.

A mile or so along a minor road outside the village is Macbeth’s Well, where he supposedly drank before the battle. Meanwhile, Macbeth’s Cairn marks the spot where he was purportedly buried, to the north of the village in a copse of beech trees on Perk Hill.

Whether any of this is true we’ll probably never know, but it does add to the sense of intrigue.

However, finding these three features proved tricky.

The well was easy enough to spot, after a few wrong turns had been taken, but the cairn and stone’s whereabouts remain a mystery to me.

I find it strange that more hasn’t been made of such historic connections, whether truth or legend.

A few signposts pointing the way to the Macbeth features would help, and in turn, potentially help boost tourism in this sleepy corner of Aberdeenshire? But then again, its sleepiness is perhaps its unique selling point.

There was a bit of a fanfare here in the 1980s, however, with the filming of The Box of Delights. This quirky BBC TV series for children featured a boy entrusted with a magical box that allowed him to travel through time.

It’s no surprise. This is a magical sort of place, ripe for exploration.

- The Peel of Lumphanan is open to the public at all times, with no charge. Some might argue that it’s best appreciated from above, so if you’re lucky enough to have a drone, take it with you.

- Archaeologists found a buckle near the Peel in 1975, depicting an animal biting its tail. Theories abound – could this buckle have fastened the sword-belt of a noble in 1296?

Conversation