When the cargo steam ship Trevessa left Fremantle Australia in May 1923, it was just another delivery to the 44 men on board, including the master from Aberdeen and a crew member from Braemar.

They were a bit uneasy though, because a black cat they had adopted at Port Pirie abandoned ship before they sailed, and a pet tabby on board had died.

On this occasion it seems there was something to be said for sailors’ superstitions.

SS Trevessa was owned by St Ives company Edwin Hain and Son Ltd and the ship was en route to Durban, South Africa with a cargo of zinc concentrate.

But less than two weeks later, the routine journey turned into a nightmare when the ship sank, leaving the crew battling for their lives for more than three weeks in two small, storm-tossed lifeboats.

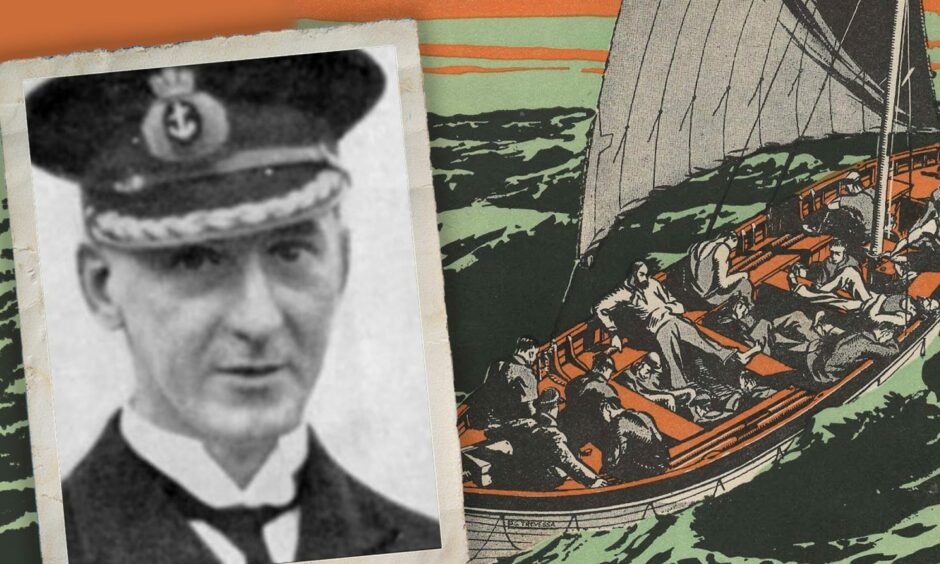

Trevessa’s wireless operator was from Braemar, her master from Aberdeen

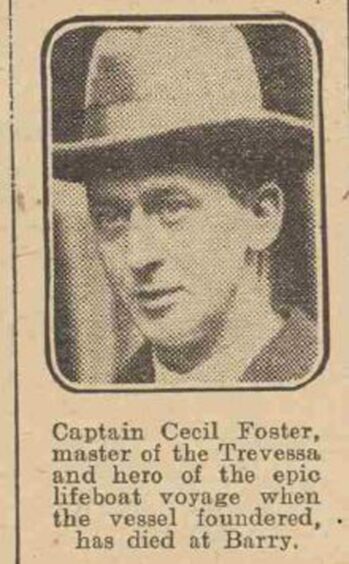

Wireless operator Donald Lamont from Braemar, and Aberdeen master Captain Cecil P T Foster, whose mother is believed to have come from Kemnay, were among the survivors, and would become national heroes when they finally made it home.

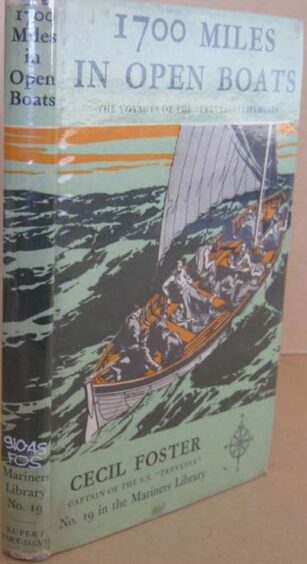

Not only that, but lessons learned from the way Captain Foster had provisioned the lifeboats would end up saving the lives of thousands of sailors caught up in similar shipwrecks for years to come.

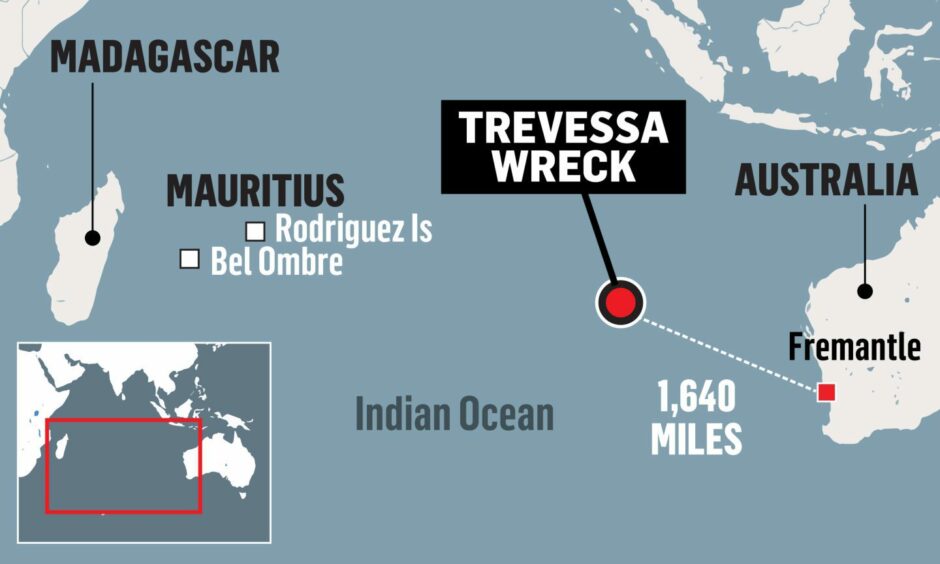

The Trevessa’s horrific ordeal started a hundred years ago today (June 4) and it couldn’t have happened in a worse place, slap in the middle of the Indian ocean, more than 1700 miles off Mauritius.

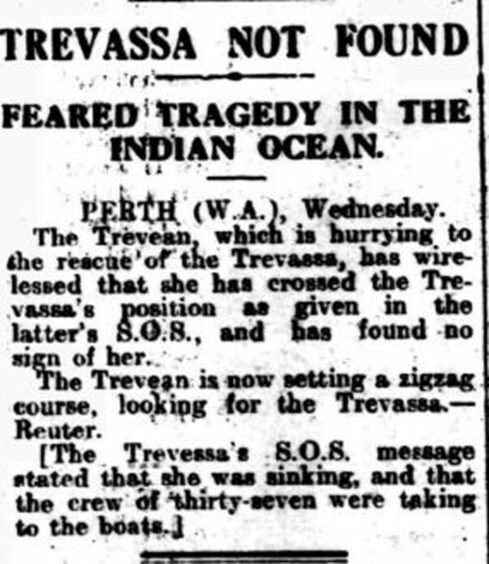

It was wireless operator Donald Lamont who sent out the SOS: “SOS de GCVJ s.s. Trevessa lat 28-45S long 85-42E sinking rapidly – crew taking to boats.”

Son of taxidermist who created ballroom at Mar Lodge, Braemar

Donald James Lamont was the son of John Lamont, taxidermist, who designed and executed the Stag Ballroom at Mar Lodge, Braemar.

By an unfortunate twist of fate, Donald had joined the ship at the last minute to replace an operator whose wife was seriously ill.

Trevessa took two hours to sink after water got into her no 1 hold, jampacked with zinc concentrate.

The substance is almost impervious to water, so converted the hold into a watertight compartment, preventing the water from reaching the bilges and tanks, where it could be pumped out.

Captain Foster realised it was game over in the early hours of June 4 when he heaved the ship too in the teeth of the storm, and realised she wasn’t lifting to the seas as she should.

Abandon ship order given

He gave the order to abandon ship and was the last to leave at 2.15 am.

Donald was one of the last off, desperately trying to keep the lifeboat from getting entangled with the ship’s side as she slid below water level.

Half an hour later the ship plunged headfirst into the deep.

Vessels steamed to her aid in response to her SOS, but by the time they got there, they were unable to find any survivors, just a few scraps of wreckage.

All souls on board were presumed dead.

The nearest ship, SS Treganna, also owned by Edwin Hain and Son, was 400 miles away but due to the severity of the storm couldn’t steer direct, and could only achieve seven knots.

The Trevessa survivors were on their own.

Foster spent his early years in Aberdeen

But Captain Foster was a cool customer who had already been through hell in World War One.

The son of a merchant seaman, Foster was born in Malta in 1890, and spent most of his early years in Aberdeen before his father’s work took the family to Barry, Wales around 1902.

He was torpedoed twice within sixteen hours in two different ships in World War One, and spent nine and a half days in a boat in the Atlantic before landing in Spain.

Twelve of the 31 men in that boat died from cold and exposure.

From this he learned that many men died because the survival rations stowed in lifeboats were completely inappropriate.

Salty rations deemed inappropriate

They were mainly tinned fish or meat, highly salted and therefore leeching the moisture from the already dehydrated sailors.

Foster got on to Edwin Hain, his employer, to change the lifeboat rations, substituting condensed milk and ship’s biscuits, a hard wheat biscuit which was, crucially, saltless.

But the rations didn’t come pre-stowed in the lifeboats, so in the teeth of the gale, the crew had to undertake the dangerous task of bringing the provision from the storeroom across the deck and up a ladder to the level of the lifeboats.

Each lifeboat received three cases of condensed milk and six tins of biscuits, along with cigarettes and tobacco, the operation taking place when the ship was almost underwater.

Navigating by the stars was the only option

There was no time to get any more in, alongside water, the vital chart and sextants. Old-fashioned navigation, using the sun and the stars, would get them on the right course,.

All this was happening in the dark, in mountainous seas. Surviving even that, and managing to jump into the boats at the right moment without ending up blown off or sucked into the deep is already testament to the men’s seamanship.

One man did fall in, but he was quickly pulled aboard.

Twenty men ended up in the captain’s boat, including Donald Lamont and the captain himself, three Irish, two Welsh, two Burmese (Myanmar), two Arabs, two Portuguese West Africans and one Indian.

In the second boat, skippered by First Officer JC Stewart Smith, there were 24 men, including eighteen from different parts of the UK, a Swede, an Afghan and four Indians.

At first the two boats tried to keep within sight of each other, while also having to carry out vital repairs on their battered craft.

It made no sense to head back to Fremantle because it would have meant battling against the currents.

Mauritius was more than 1700 miles away, but at least the wind was behind them.

Aboard the two boats, rations were tiny and closely guarded by their skippers. About six tablespoons of water a day, four teaspoonfuls of condense milk twice daily and two biscuits.

The lifeboats go their separate ways

After six days sailing together, the two lifeboats decided to separate to try and increase the chances of being spotted.

The captain’s boat had a bigger sail and was faster, so rapidly drew ahead.

In a horrible twist of fate, they didn’t realise that SS Treganna, sent to their rescue, was only 85 miles from the two boats at that point, and less than 100 miles from them at various points over the next few days.

Sadly there were two losses from privation on the captain’s boat, Jacob Ali, the Indian, and Mussim Nagi, the Arab.

Occasionally manna from heaven would appear in the form of life-saving rain, but plain sailing it wasn’t.

There were more storms to contend with and constant running repairs to make to keep afloat as the men’s moral waned and their bodies weakened.

Land ahoy!

On the twenty-third day, June 26, the carpenter on Captain Foster’s boat spotted land, Rodriguez Island, about 15 miles away.

Ever cautious, Foster didn’t plunge ashore as he was unfamiliar with the coast, but eventually with the help of a fisherman, they made it to safely to shore.

But FO Smith’s boat was still battling on, and things were bad on board.

They lost eight men, some crazed by dehydration and killed by drinking sea water. Others died of illness and exposure, and one died when he stood up to try and catch rainwater during a squall and fell overboard.

Against all the odds, the little boat made it to Mauritius on June 29, 300 miles further than Rodriguez Island.

Captain Foster had alerted the authorities and the warship HMS Colombo was sent out to look for them, but Smith’s boat beat them to it, landing at Bel Ombre, Mauritius with the men on their last legs.

Later Colombo would carry the survivors to be reunited with their shipmates in Rodriguez.

Astonishingly, both boats reached safety with a reserve of rations, prolonging their chance of survival if they had missed the islands.

A hero’s welcome

At home, the press had reported on the search efforts once the SOS had been picked up from Trevessa, but by June 20 concluded that the crew hadn’t taken to the lifeboats and were lost.

After a few weeks’ recovery time, the Trevessa survivors were returned to England aboard RMS Goorkha of the Union Castle Line.

They received a hero’s welcome in Gravesend and were the talk of the country for several weeks.

“Their arrival evoked a great and spontaneous outburst of welcome,” reported the Yorkshire Post.

“Sirens sounded from the moment the Goorkha entered the Thames, hundreds of people waved good cheer from both sides of the river… dozens of anchored vessels screamed out cordial recognition of the gallant seamen show now reached the end of a journey at one time marked by dreadful suffering and tragedy.”

FO Smith’s wife came to meet him from Edinburgh, but Captain Foster’s wife in Barry was too ill to make the journey.

Relatives wept for joy, and, reported the Yorkshire Post, one woman was heard crying out, “Look at Joe, he don’t seem a bit the worse for what he has gone through.”

Captain Foster was said to look the picture of health, and would only say: “There was a wonderful feeling of comradeship amongst us.

“That feeling kept us up, and kept us from giving up the hope that in the end we should all be saved.

“I don’t think any of us really lost hope.

“A finer crew no skipper ever had.”

The crew in turn praised their skipper, saying he would lead singing when spirits were low, and kept them going with his “cheeriness and generally encouraging conduct.”

‘Never say die’

One hardy survivor from FO Smith’s boat, R. Jones from Liverpool said his motto was ‘Never say die’ and he would be away at sea again in another week despite being in the water fifteen times and torpedoed nine times; his love for the sea would never die.

At Gravesend the men were given lunch by the Seafarers’ Joint Council, with the town’s mayor telling them they would go down in history as heroes.

“When we read of the privations they endured, we got the measure of their pluck and discipline.”

Foster and Smith were each awarded Lloyd’s Silver Medal in recognition of discipline, endurance and seamanship and were invited to Buckingham Palace to meet King George V.

The crew received a share of £1,453, collected by the Lloyd’s committee.

Donald Lamont was so weak by the end of the ordeal that he had to be helped to sit upright.

He later wrote: “It took an hour to eat a morsel of biscuit, our mouths being that devoid of saliva that the biscuit after mastication was like dry flour and blew out of our mouths like dust.”

He later published his account, The Last Voyage of the SS Trevessa.

After a month’s sick leave he joined Marconi where he served 39 years before emigrating to New Zealand.

During the war Donald served with the Third Glasgow Batallion, Home Guard and later with the Gordon’s Home Guard Batallion until 1956.

He died in 1983, aged 84, with his grave in Birkenhead-Glenfield cemetery, Auckland, bearing the epitaph: A Survivor of S.S. Trevessa 1923 Cherished memories of beloved Dad A good and kind man at rest R.I.P. “Gus am bris an latha”

Captain Foster also wrote up his account, 1700 Miles in Open Boats.

He returned to Barry to be with his wife Minnie and died there aged 43 in 1930.

Conversation