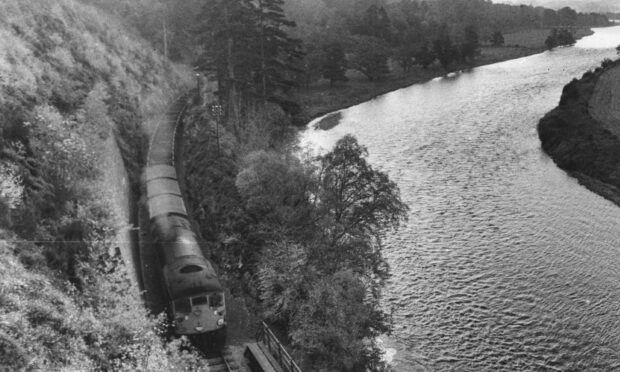

Building the scenic Strathspey Railway along the meandering and rippling River Spey 160 years ago was a feat of engineering.

Despite being built by hand through frowning rock faces and narrow ravines, the railway took little more than a year to build.

Described as winding “like the coils of a huge serpent among romantic scenery”, the accomplishment of Strathspey Railway was celebrated widely.

Navvies built Strathspey Railway

In November 1860, proposals were first mooted for a railway between Dufftown and Abernethy.

It was to cover 34 miles between a junction with Keith and Dufftown Railway and the Inverness and Perth Railway junction.

Work was well under way by December the following year with six locomotives already on order from Robert Stephenson and Co in Newcastle.

Like all railways, the hard and dangerous work to establish the new Strathspey line was undertaken by navvies.

Navvies were labourers who, armed with little more than spades and pickaxes, dug out 50ft railway cuttings and long tunnels for tracks.

Although well-paid by Victorian standards, navvies lived and worked in poverty, and hundreds died each year establishing Britain’s railways.

They were nomads who travelled to new railway sites with their families, and usually slept in basic huts next to the tunnels.

Many people looked down on navvies, considering them uncouth, hard-living and hard-drinking vagrants.

But a fascinating, human interaction with the navvies building Strathspey Railway made the news in 1862.

Maverick Margaret meets the navvies

The new railway passed through the estate belonging to Margaret Macpherson Grant, an unconventional aristrocrat who lived at stately home Aberlour House.

Margaret was a bit of a maverick and deemed to be rather unladylike by society, so it was of no real surprise she befriended the navvies working alongside her land.

It was reported in the press that with “characteristic heroism” she had a look at the tunnel being built then found a wheelbarrow to pitch in.

Margaret, “in real navvie style”, then hurled a few barrowfuls of the ballast, or gravel, from the cutting to the bank ahead.

The report said: “The men who were at work seemed really astonished at the feat, and gave three hearty cheers in honour of the young lady; some even declaring that there were those at work who could not perform the part so well as she had done.”

Margaret sent her thanks to the navvies and with her “customary liberality” said she would not forget them.

The next day she fulfilled her promise and sent her butler down to serve “a most substantial dinner” to the navvies, which was received with loud cheers.

Railway completed on time and under budget

The work was carried out with such vigour that the railway opened to the public a whole month ahead of schedule on July 1 1853 instead of the estimated August 1.

And remarkably it was also within budget, coming in at a total of £227,903.

The line cost £6,000-a-mile to build, with the remaining spend made up by procuring land and building stations.

The directors of the Great North of Scotland Railway, along with investors, inspected the new line on June 25 1863.

It was the first time a train had travelled the length of the newly-completed route from Dufftown to Abernethy.

The special train started out at Aberdeen, and upon arriving at Dufftown was decorated with flowers for the onward journey.

With seven carriages and around 150 passengers, the train stopped at every station along the way, where officials inspected the infrastructure.

The iron horse in the Spey Valley

It was reported that “at every available point knots of people collected to witness what was to many of them the novelty of a railway train”.

One of the guests joining en route was Margaret Macpherson Grant, who had so enthusiastically accommodated the railway.

An account of the occasion was recorded in the Press and Journal on July 1: “The ride, especially to those who had never beheld the grand and romantic scenery of Strathspey, was one of rare enjoyment.”

A detailed description was given of the sights and sounds as the ‘iron horse’ thundered through the Spey Valley to its Highland destination.

Mention is made of notable country residences belonging to the lairds and ladies of ‘Grant country’, and the “handsome” iron brig at Craigellachie.

Then, proceeding north, Speyside’s sentinel mountain Ben Rinnes “demanded the attention” of the passengers on the Strathspey Railway’s inaugural journey.

Bridge was feat of engineering

The steam engine pressed on, by now approaching a new crossing of the Spey – the Carron Bridge.

A vast arched, 150-ft ironwork span linking the Moray parishes of Knockando and Aberlour, it still stands today.

The impressive bridge was fabricated by Aberdeen engineers McKinnon and Co at the cost of £10,000.

Carron Bridge was the last cast iron railway bridge built in Scotland, but also provided a roadway for vehicles and path for pedestrians.

Weaving through Speyside, the train crossed the Spey again, first at Ault Airder Burn, then again over the new Balnellan Viaduct, an structure of iron lattice and girders.

As the River Spey rolled on, so did the train, huffing and puffing to Ballindalloch Station and on to Advie.

Reaching Dalvey, the engine passed through “beautifully wooded hills and valleys” for another four miles to the Jacobite battlegrounds of Cromdale.

Finally, the train approached Grantown Station against the backdrop of the distant Cairngorn hills, still speckled with snow in midsummer, before terminating at Abernethy.

A toast for Strathspey Railway

An excited crowd was ready to greet the first echoes of steam as the train pulled into Abernethy.

The arrival of the railway saw the village renamed Nethy Bridge to avoid confusion with Abernethy in Perthshire.

With appetites whetted by the bracing Highland air, the special guests arriving at Abernethy enjoyed a feast in the decorated engine shed.

Rather at odds with the industrial surroundings, the elegant banquet featured tables adorned with champagne and fruit.

A hearty toast was made to the “success of the Strathspey” and to the health of its engineers.

Although not everyone was so welcoming of the new trains.

It took a while for residents of this peaceful corner of Scotland to get used to the advent of the railway.

When the train made its journey by Glaick, not far from Grantown, an elderly lady heard it and believed the devil was upon her.

Startled, she hid in a lime kiln while cursing the engine in Gaelic.

If you enjoyed this, you might like: