The arrival of the National Health Service 75 years ago was a time of both hope and uncertainty in Aberdeen.

While there had been health provision in Scotland prior to July 5 1948, it was not universal or free at the point of use.

Before the NHS, Aberdeen’s poor had access to healthcare through charitable hospitals, and the 1845 Poor Law (Scotland) Act enforced the provision of healthcare by councils.

But this relied on people accepting charity, which many were reluctant to do.

It also needed co-operation between local authorities and the landowners who provided a lot of the poor relief funding.

Poor people who didn’t live in poorhouses could also attend voluntary hospitals.

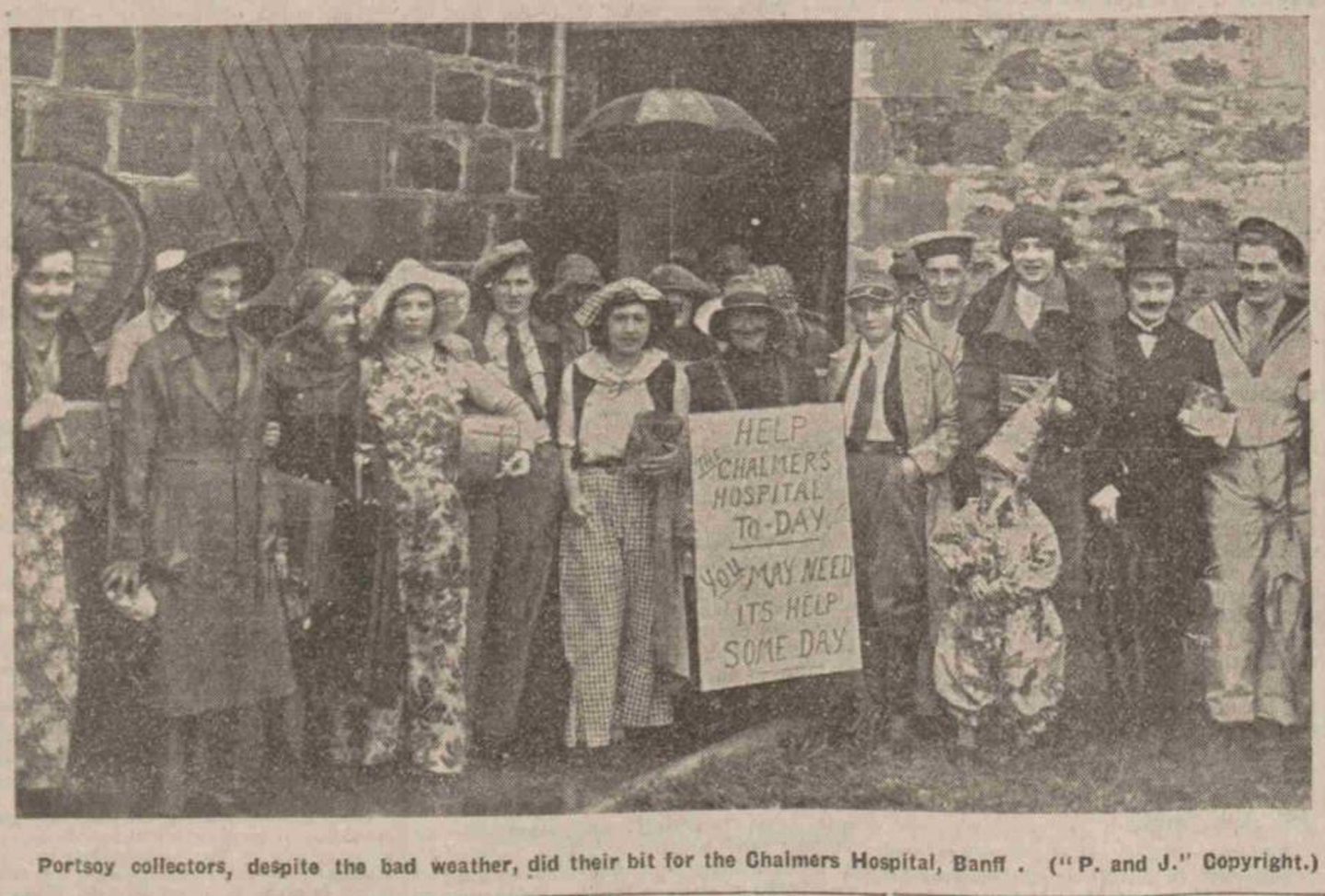

And when it came to building hospitals, costs were met through public subscriptions and fundraising.

Healthcare was also provided through insurance-based schemes for those who weren’t impoverished, but weren’t able to pay themselves.

But only the person paying into the policy was eligible, which meant spouses and children were excluded.

So for many, discomfort and disease was simply part of daily life.

National Health Service based on Highland healthcare

While there was excellent healthcare available prior to the NHS, it was at best patchy – in modern terms it would be described as a ‘postcode lottery’.

In Scotland, the Dewar Report of 1912 set out a case for healthcare reform in remote areas.

A committee led by Inverness MP John Dewar raised grave concerns about living standards and healthcare provision in the Highlands and Islands.

Scattered crofting populations and lack of regular wages to pay insurance was a barrier to seeking medical help.

The committee travelled to the farthest reaches of the Highlands and Islands to see and hear for themselves the difficulties people faced in healthcare.

The result of the findings was the Highlands and Islands Medical Service.

It was built on the principle that healthcare was a human right, regardless of social stature or geography.

Doctors were paid an annual wage with grants available for transport and accommodation.

The aim was to improve access to medical services for all, for a small fee.

Existing hospitals were reorganised, while it was recommended that community and cottage hospitals were built.

Healthcare ‘from cradle to grave’, but some locals were initially suspicious

People forget just how remote parts of Aberdeenshire were in the early 20th Century, and most communities relied on a cottage hospital nearby.

The doctors of Aberdeen and its surrounding districts were rightly proud of the medical service they provided pre-NHS.

Therefore there was a great deal of suspicion when there was talk of a National Health Service from the new post-war health minister Aneurin Bevan.

It was part of a radical programme of welfare reform by the Labour Party based on the Beveridge Report.

The party enjoyed a shock election victory in 1945, ousting Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his wartime coalition.

Labour, under the leadership of Clement Attlee, quickly set to work implementing a new welfare state that would take the nation ‘from cradle to grave’.

And this was a nation fatigued by war, austerity and, prior to that, the Great Depression. It was a nation ripe for change.

Aberdeen doctors likened Bevan to Hitler

But it wasn’t a sentiment shared by all doctors in Aberdeen.

The year leading to the establishment of the NHS had been a bumper one for Aberdeen Maternity Hospital, with 3000 babies born.

In general, the local healthcare provision was ticking along nicely.

In January 1948, just months before the NHS was to be implemented, the Aberdeen and Kincardineshire branches of the British Medical Association were not happy.

Following the largest-ever meeting held by the division, they decided to reject the National Health Service Act.

Doctors feared that as salaried men they would become “servants of the state instead of being the servants of their patients”.

Private healthcare was also very lucrative.

They stated: “The National Health Service Act of 1946, in its present form, is so grossly at variance with the essential principles of our profession that it should be rejected absolutely by all practitioners.”

More so, they argued that in raising their concerns with Bevan he was “unfriendly” and “impolite”.

One member said: “He had stood up like a Hitler and said ‘you are for it'”.

While another doctor said in Aberdeen “no patient, under the present system, no matter how poor, had been deprived of the best medical attention”.

Members felt they were “doing a service to their country” by rejecting the “cunningly-devised scheme”.

Doctors backed NHS at eleventh hour

Bevan eventually won doctors’ support by allowing them to continue to treat patients privately while working for the state NHS.

By April 1948, the Edinburgh division of the BMA had decided to join the NHS and urged their northern counterparts to do the same.

And in May, the BMA as a whole recommended that its members co-operated with the government in launching the NHS.

The BMA had warned “the medical profession would forfeit the support of the public” if it rejected Bevan’s compromise.

On May 17, just shy of seven weeks before the NHS was to launch, the doctors of Aberdeen and District reversed their opposition.

The doctors thought further fighting would “split the profession in half”.

No fear for future of healthcare in Aberdeen as NHS ‘passports’ issued

The NHS Executive Council for Aberdeenshire and Kincardine met in Aberdeen one month before the NHS was launched.

Each citizen in Scotland had to fill out a white EC1 card, or ‘passport’, for their new state healthcare system.

At the executive meeting, one Aberdeen doctor proudly exclaimed that on the same day he had received a white card for a day-old baby, and a 97-year-old woman.

It was a statement that truly embodied the ‘cradle to grave’ aim of the NHS.

But it was still an uncertain time for those who had helped establish Grampian’s healthcare system.

Aberdeen Town Council took a farewell tour around its hospitals before they transferred to the NHS.

In a speech, Lord Provost Duncan Fraser said: “I have no fear of the future. We are passing from one stage to another and I am perfectly sure that the medical services will be in good hands.”

Haircare in healthcare

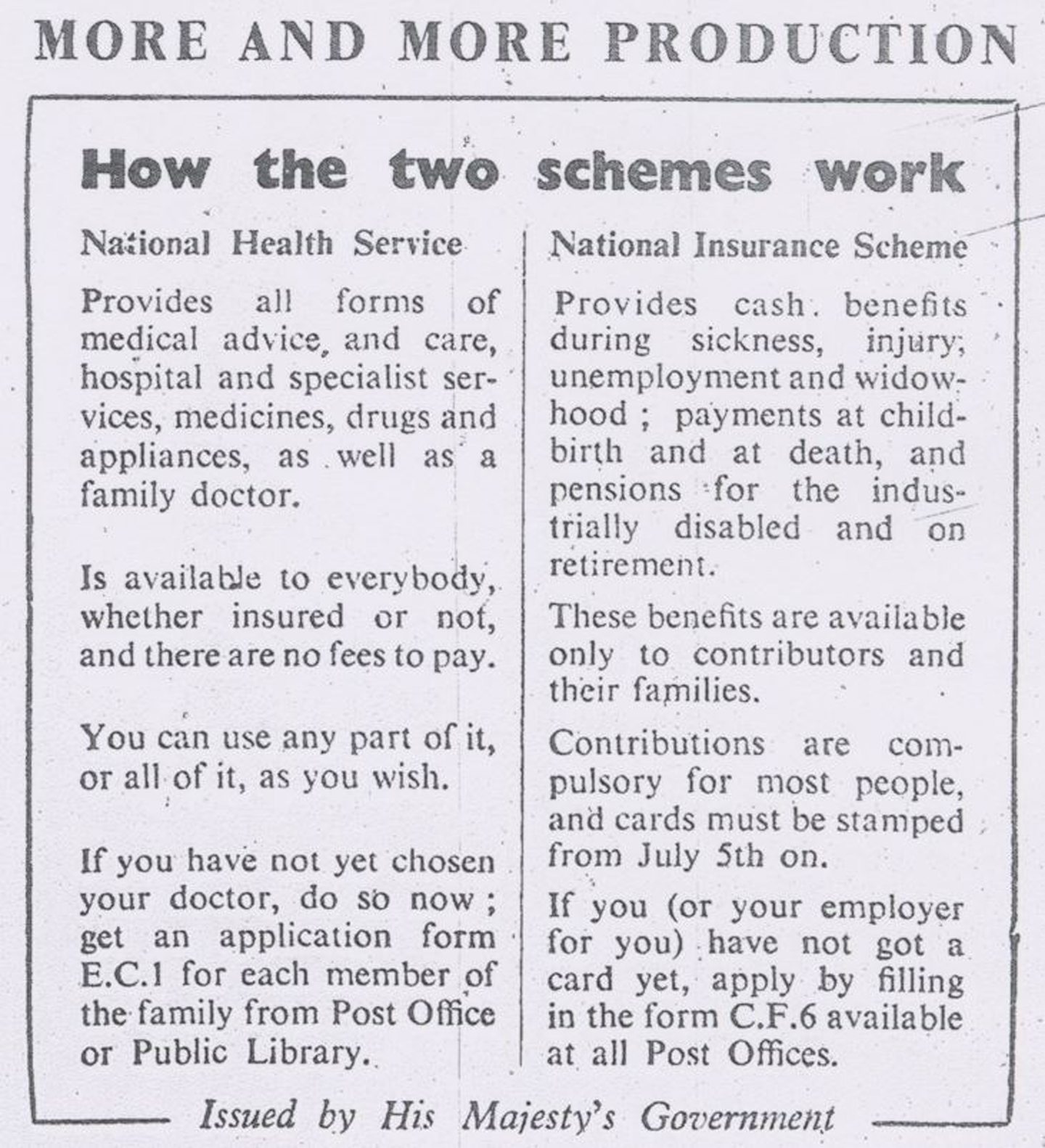

On the day the NHS launched, public information announcements were carried in all newspapers.

The adverts explained that there was more security in universal healthcare than in insurance.

But to fund this out of taxation, the nation had to be more productive.

Of course, there wasn’t an unlimited supply of money to pay for treatment and goods.

After its launch, the Aberdeen Executive Council for the NHS met monthly to discuss claims.

In March 1949, the committee discussed whether a full-time hairdresser should be provided in hospitals under the NHS.

A hospital hairdresser had previously been provided by Aberdeen Town Council.

It was said by Professor John Cruickshank that “nothing raises the morale of a person in hospital more than to be properly shaved and to have his hair attended – and this includes women as well”.

It was agreed to provide a hairdresser, and in the first appointment of its kind in the north-east, a ‘social therapist’ to provide recreation and games for mental patients.

Teething problems

Later, at the committee’s meeting on June 13 1949, the case of an Aberdeen man’s damaged dentures were considered.

He had laughed so hard at a funny film that his false teeth fell on the floor of the cinema where they were trampled.

The NHS in Aberdeen asked the man to pay for three-quarters of the cost of his treatment.

While another had claimed for new dentures after his previous set were “lost over the side of a ship when seasick”, and had to meet half the cost for replacements.

The dental committee took a dim view of both men’s claims.

Executive council chairman Mr Bain commented: “People who do not take care of appliances supplied to them under the NHS will have to pay a suitable amount towards replacement.”

But the Press and Journal was accused of giving too much publicity to cases where people appeared to be abusing the NHS.

In November, Mr Bain wanted to highlight how well the city transitioned in adopting the NHS.

He said having a group of hospitals like those at Foresterhill “was the aim of every city in the country”.

And added: “When the transitional period is past, we should have a service which will be the envy of the whole world.”

If you enjoyed this, you might like: