Imagine standing where the Bon Accord St Nicholas Centre is now, looking up towards George Street with independent shops as far as the eye can see. Many Aberdonians won’t need to imagine, because they remember the city centre before the heart was ripped out.

Historically, major developments in Aberdeen have been dogged by controversy.

In recent times, Union Terrace Gardens’ makeover has dominated headlines and split opinion, with rows continuing for a decade after a public referendum.

But the wholesale redevelopment of St Nicholas Street and George Street was the Union Terrace Gardens wrangle of the ’70s.

It was a planning blight in Aberdeen that started in the 1960s and courted controversy for almost 19 years before the wrecking ball moved in.

There had been a public inquiry, endless debates and campaigns, then in 1979, the Scottish Office demanded another public inquiry, this time to hear objectors’ views.

But it wasn’t just Aberdeen’s built heritage at stake – many argued its future was too.

This is the story of how St Nicholas Street and George Street were transformed from historic high streets to what we have today.

1970s: Aberdeen still had a traditional city centre, but oil was soon to change all that…

The 1970s saw a transformation in fortunes for Aberdeen when the discovery of oil in the Forties Field brought the boom times to town.

By the end of the decade, the streets were practically paved with black gold – the city was prospering.

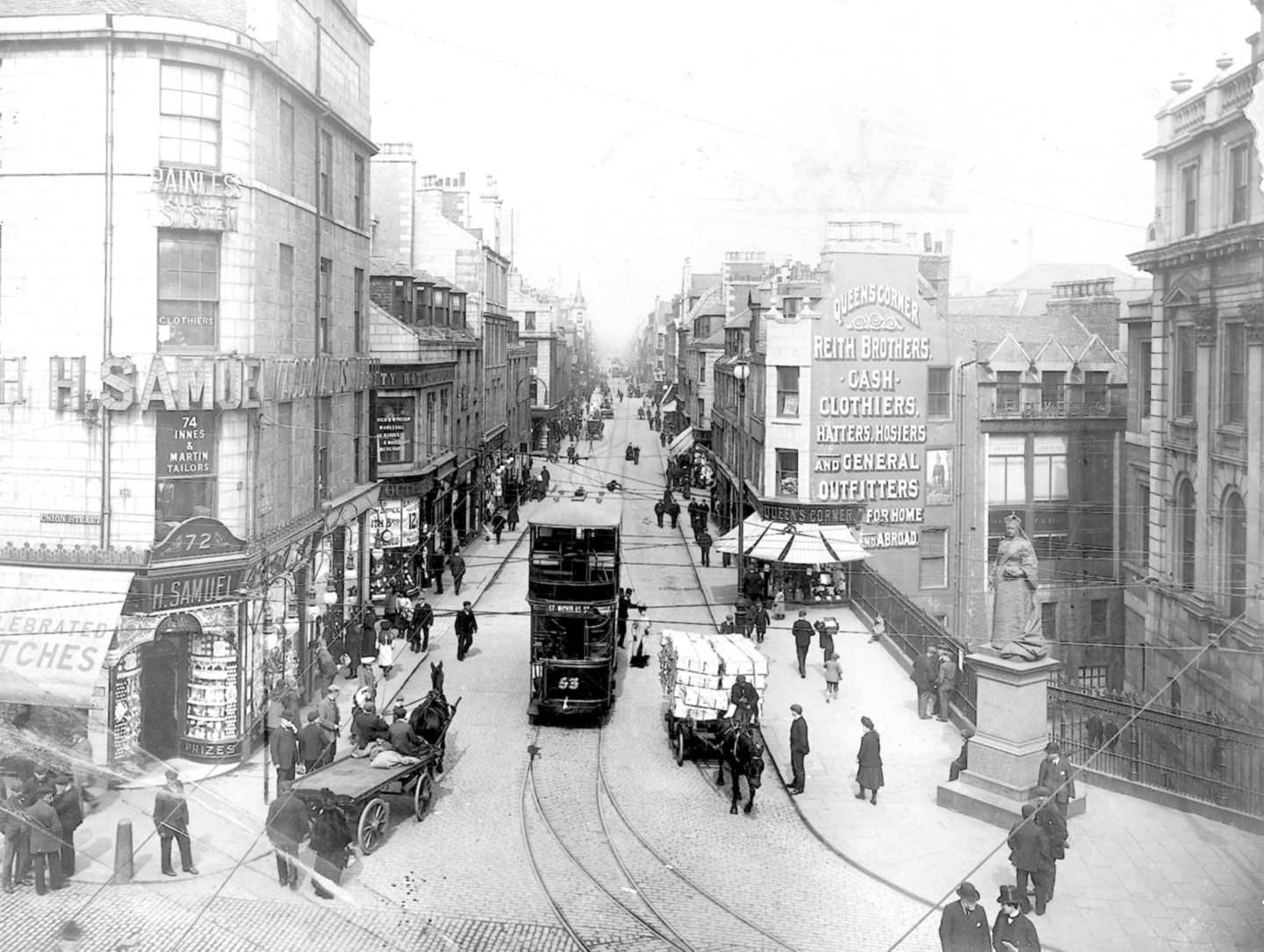

But at its heart, Aberdeen was still a traditional city with a relatively close-knit centre.

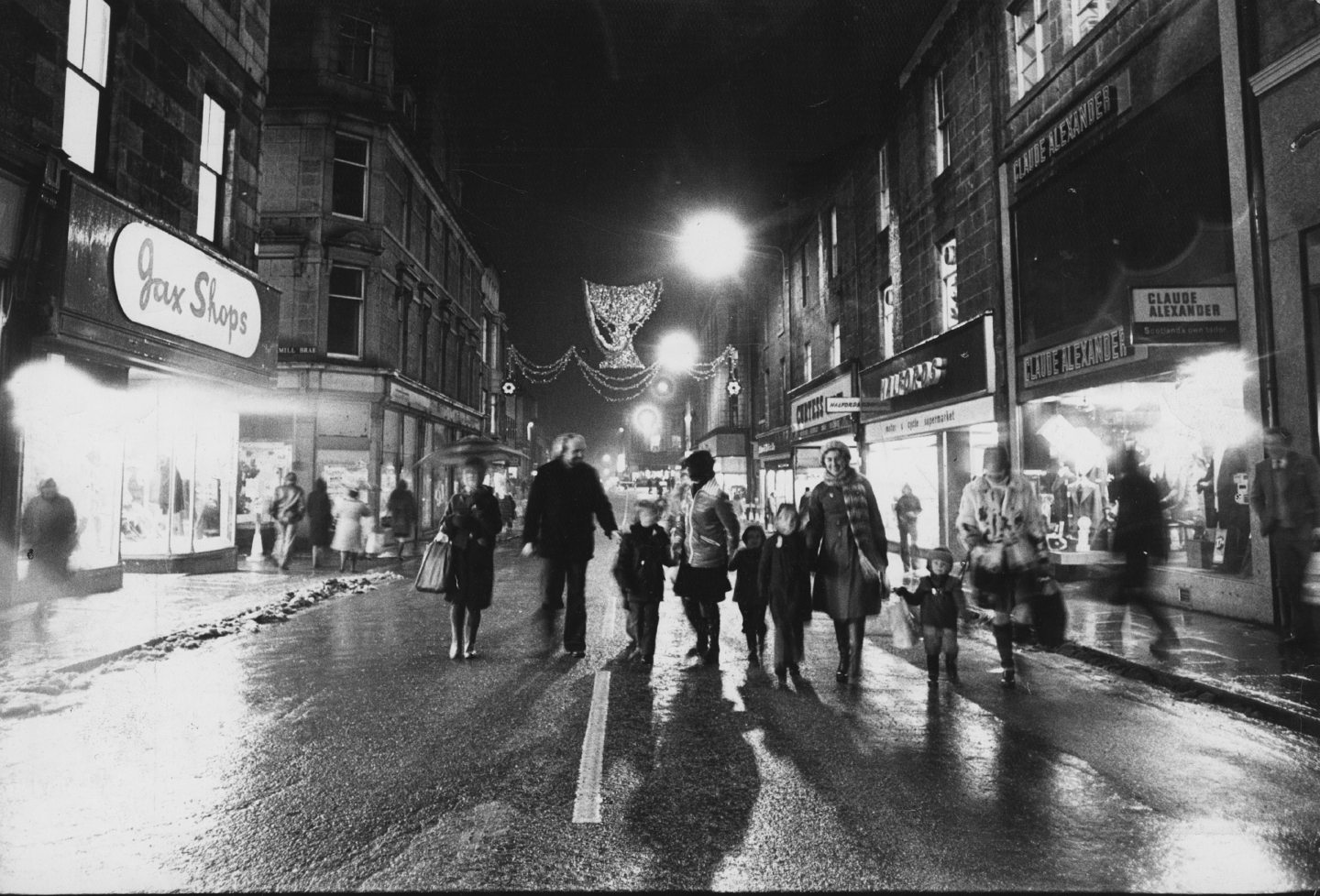

The well-known family businesses that had existed for decades still proudly stood firm on Union Street, St Nicholas Street and George Street.

But on the cusp of a new decade, change was afoot.

In one of its final editions of the 1970s, the Press and Journal stated “the 1980s could see Aberdeen’s city centre change more radically than at any time in the last 150 years”.

Plans to change St Nicholas Street went back to 1940s

The prediction had been made before – plans to pedestrianise and modernise St Nicholas Street were nothing new.

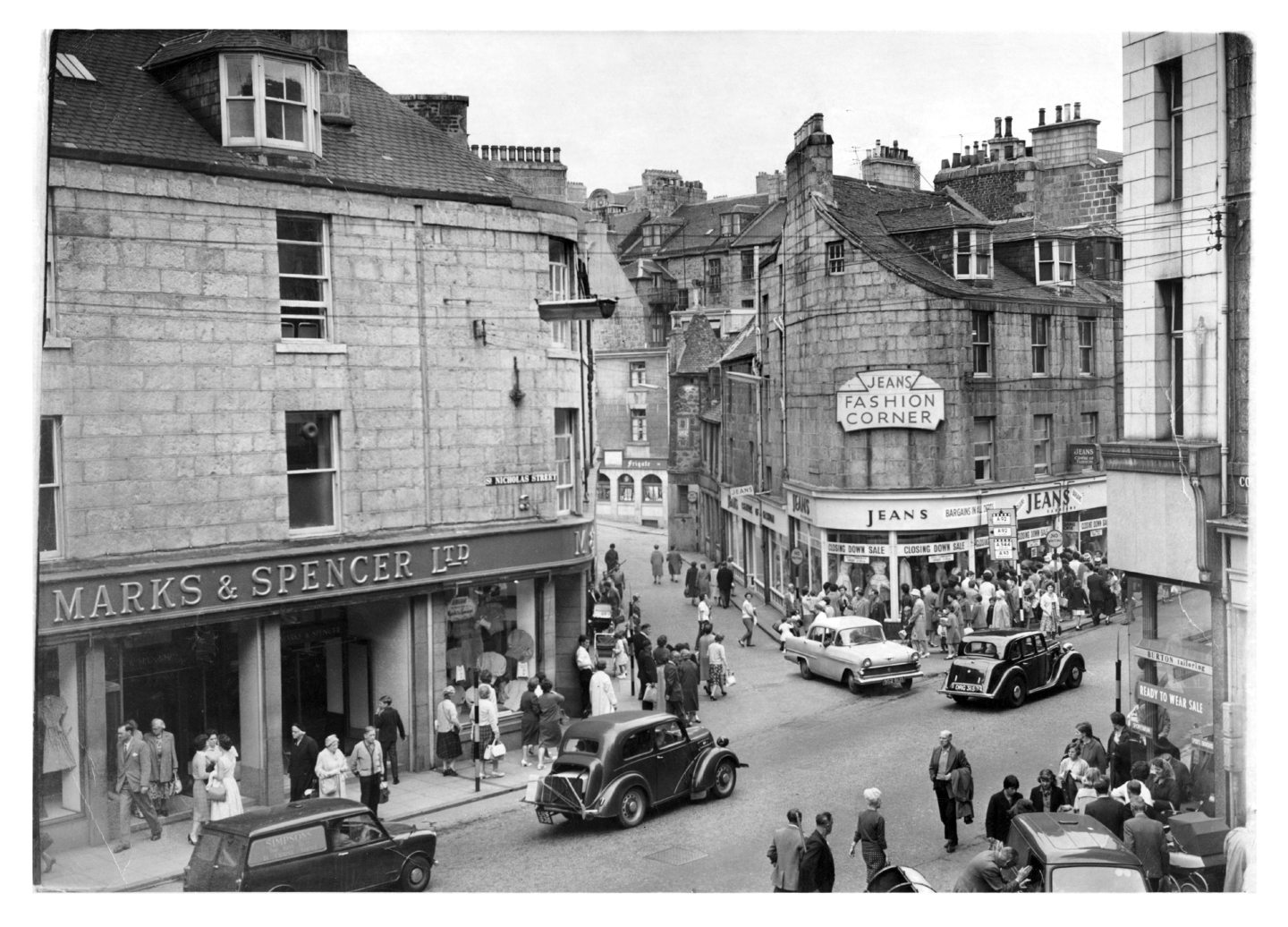

In 1962 it was agreed the street would be widened, but even this proposal was first mooted in 1944 when Marks and Spencer acquired its city-centre site.

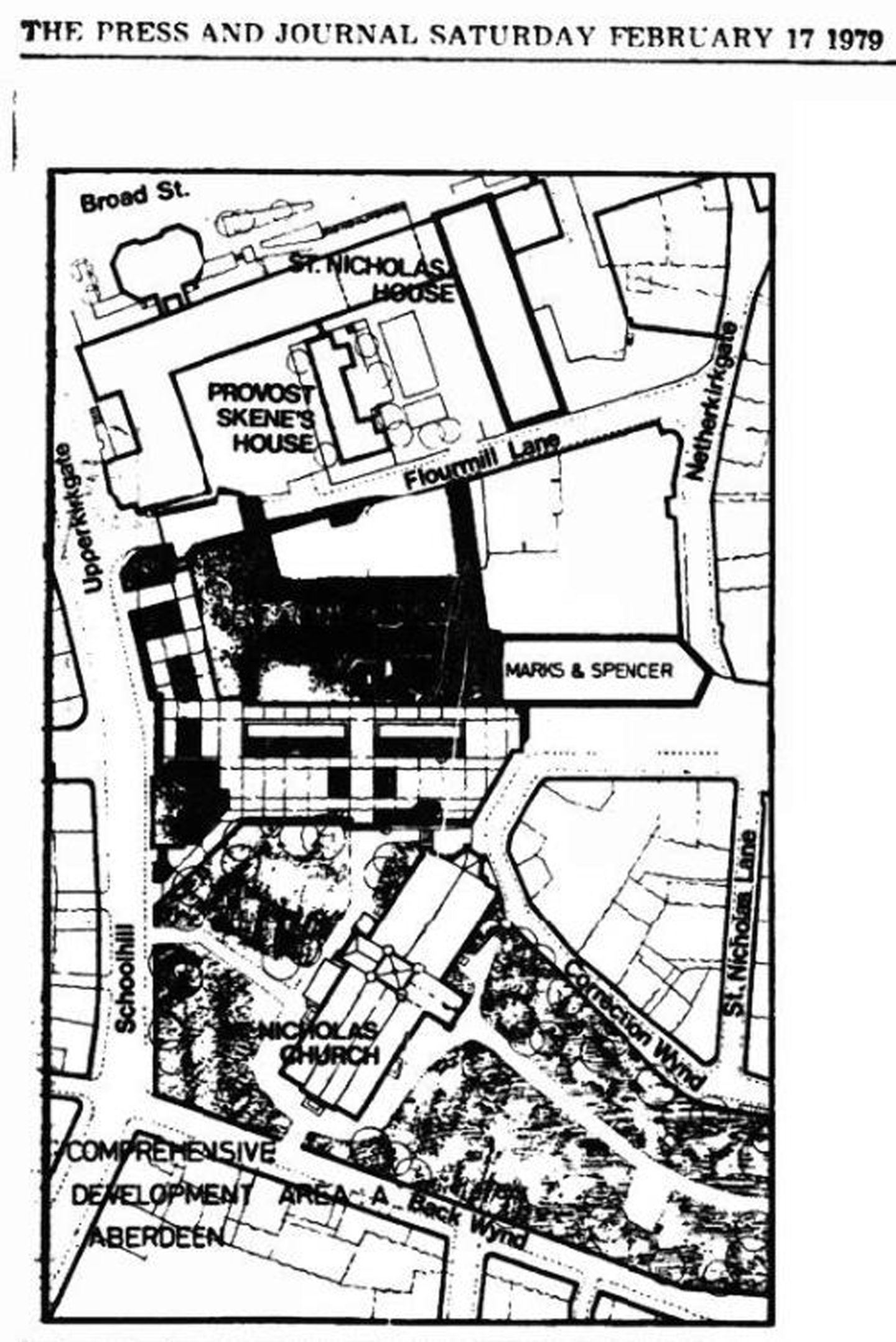

Finally in 1964, the plans came to fruition with the demolition of the small M&S and ‘island of buildings’ behind it, to make way for its giant modern-day store.

The gigantic premises stretched across Netherkirkgate and eradicated the old-world feel of neighbouring wynds.

Most significantly of all, the development saw the removal of the ancient Wallace Tower, a 17th Century fortress house rebuilt near Seaton.

The street was also widened taking the pavement up to the Clydesdale Bank, covering Carnegie’s Brae below.

And in 1968, St Nicholas House, the former Aberdeen City Council headquarters, was erected on an area cleared of old tenements.

Ultimately, it became a building Aberdonians loved to hate; a shabby, concrete totem to poor planning decisions.

But the redevelopment proposals the following decade were more radical still, representing a wholesale redesign of the city’s traditional heartland.

Shopkeepers’ concerns over plans to demolish St Nicholas Street

In 1979, the council and developers wanted to entirely change the streetscape.

They proposed removing historic shops and buildings to pedestrianise the street and create a covered walkway of shops.

In the planning brief, developer GUS said it intended to “demolish all existing properties” on St Nicholas Street, and “none had any architectural or historical significance”.

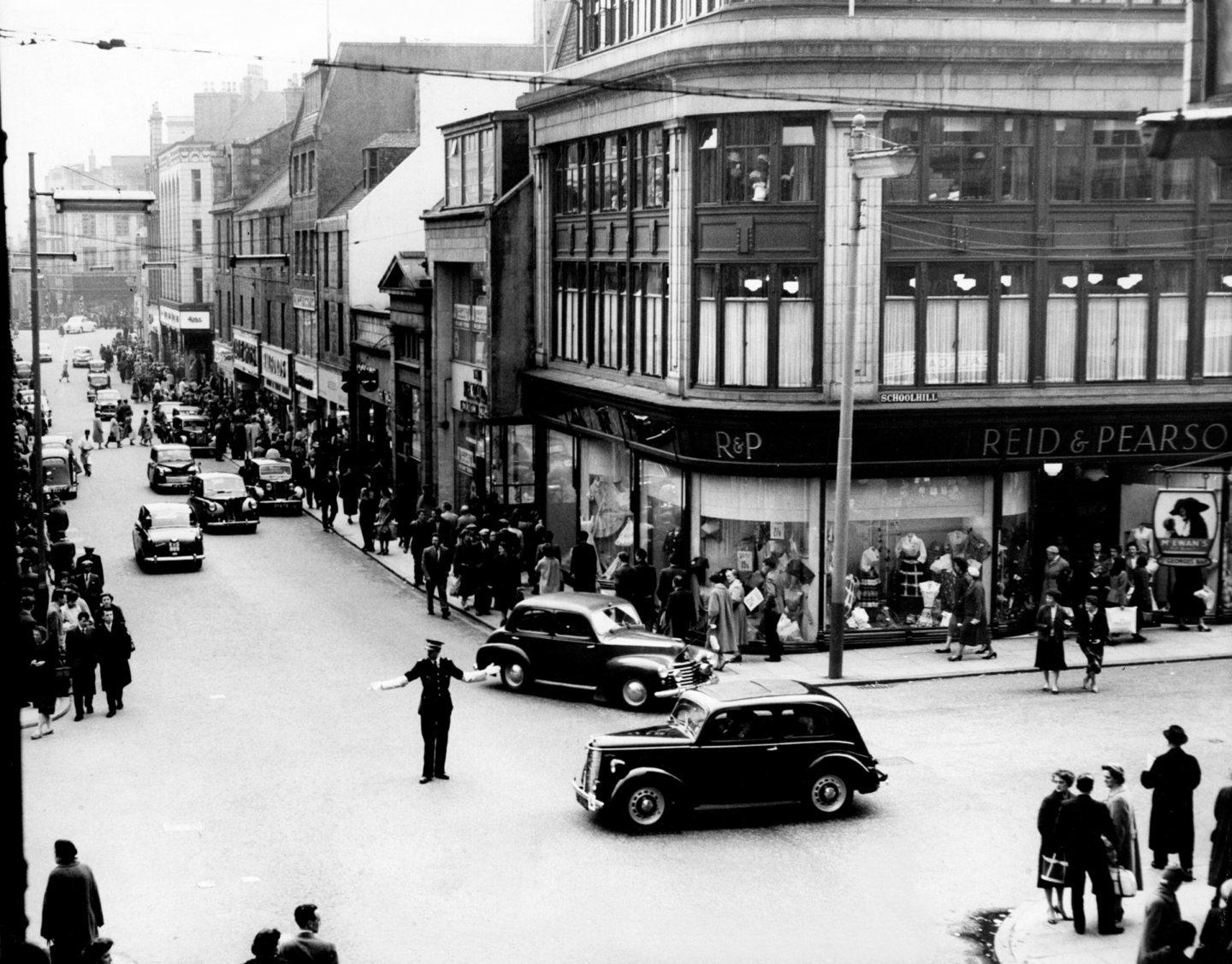

St Nicholas Street was once lined with shops with traditional double-fronted facias, canopies and curved windows displaying wares.

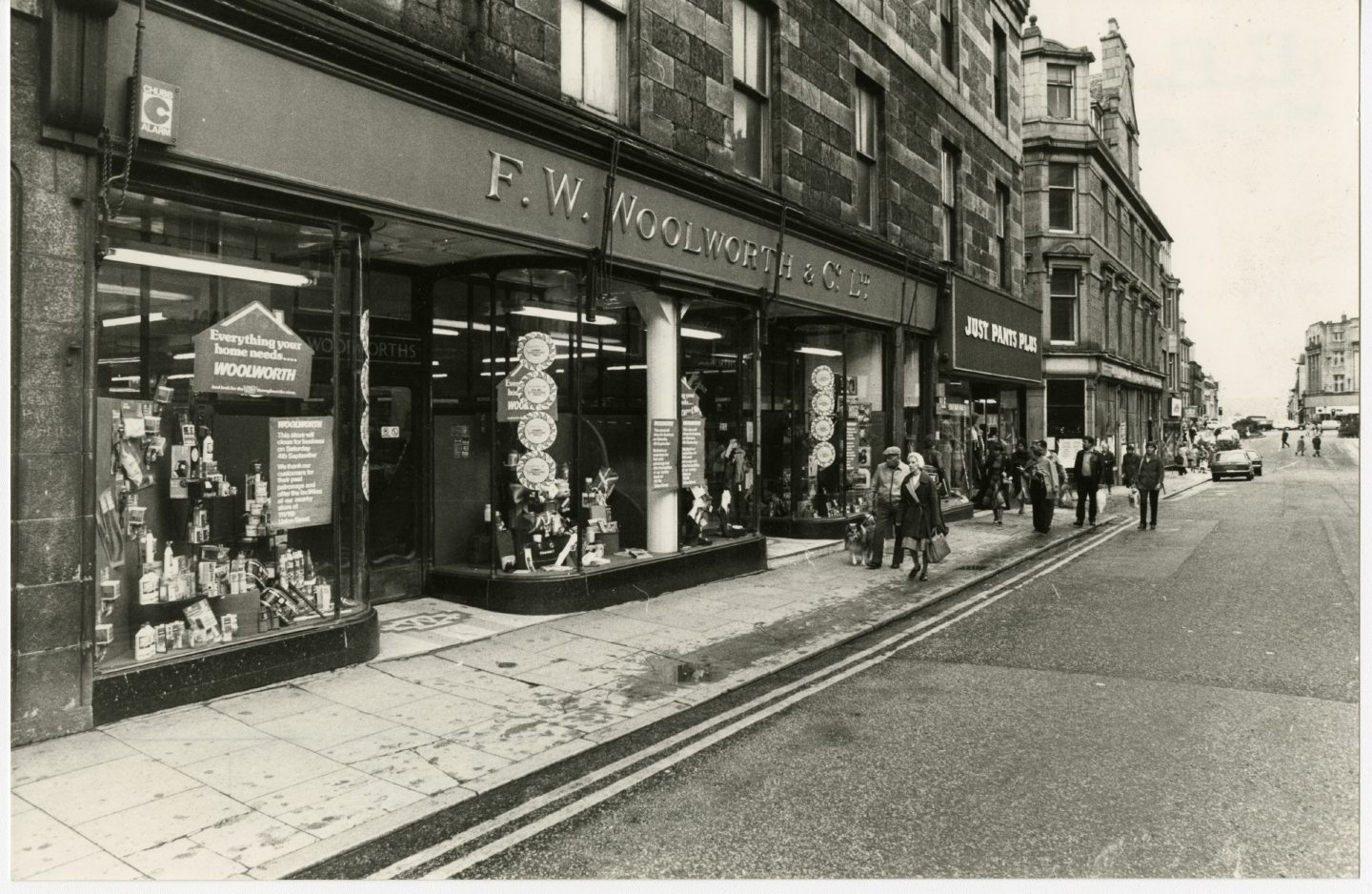

So much time was spent on plans and discussions, that over time, the shops had been allowed to become rundown.

This perpetuated the council’s argument that a whole-scale redevelopment was the only answer, and with no alternative, the modern proposal was largely unopposed.

That is, except by shopkeepers and traders, who felt the loss of this thoroughfare to George Street would take the city back to medieval times.

Would city be robbed of its built heritage?

The plans went back and forth between the council, developers and the government’s Scottish Office reporters.

Government planning reporters raised doubts over the scheme’s future and commercial viability. Even in 1979 it was felt this lacked longevity.

While the approach to planning hadn’t reached the level of preservation towards built heritage these days, there was already a collective shift away from extreme, large-scale city redevelopments.

Lessons were starting to be learned from post-war demolition schemes that famously robbed Glasgow of Victorian tenements, notable churches and edifices.

A public inquiry, however, found favour in a ‘Comprehensive Development Area’ for St Nicholas Street (area A) and George Street (area B), and the council pushed ahead.

The P&J reported: “What appeared to be the final decision on the matter was taken at a district council meeting this year when a firmly-whipped Labour group, with some support from leading Conservative councillors, overcame Liberal-led opposition and approved the deal with developer Bredero.”

At the time, it was dubbed the ‘longest public inquiry in Aberdeen’s history’

But that wasn’t quite the end of the road for St Nicholas Street and George Street.

The traders took matters into their own hands and came up with their own alternative scheme, urging councillors: “Don’t break the heart of the granite city”.

In November 1979, then-Scottish Secretary George Younger demanded another public inquiry.

This time listening to the objectors who had had compulsory purchase orders slapped on their George Street premises to make way for a £54 million shopping mall.

By 1981, it was still ongoing, dubbed “the longest public inquiry in the city’s history”.

With land and funds already earmarked, the council argued it was the only viable way to restore a dilapidated area.

One George Street shoe shop owner argued that Aberdonians would be paying for the development for the next 125 years.

But the Scottish Secretary said it was a planning decision, not a fiscal one.

A choice between demolishing and rebuilding the lower part of George Street, or the traders’ desire for “organic regeneration”; restoring the best and rebuilding only what was necessary.

Farewell to old shops to make way for the new, as demolition begins on St Nicholas Street

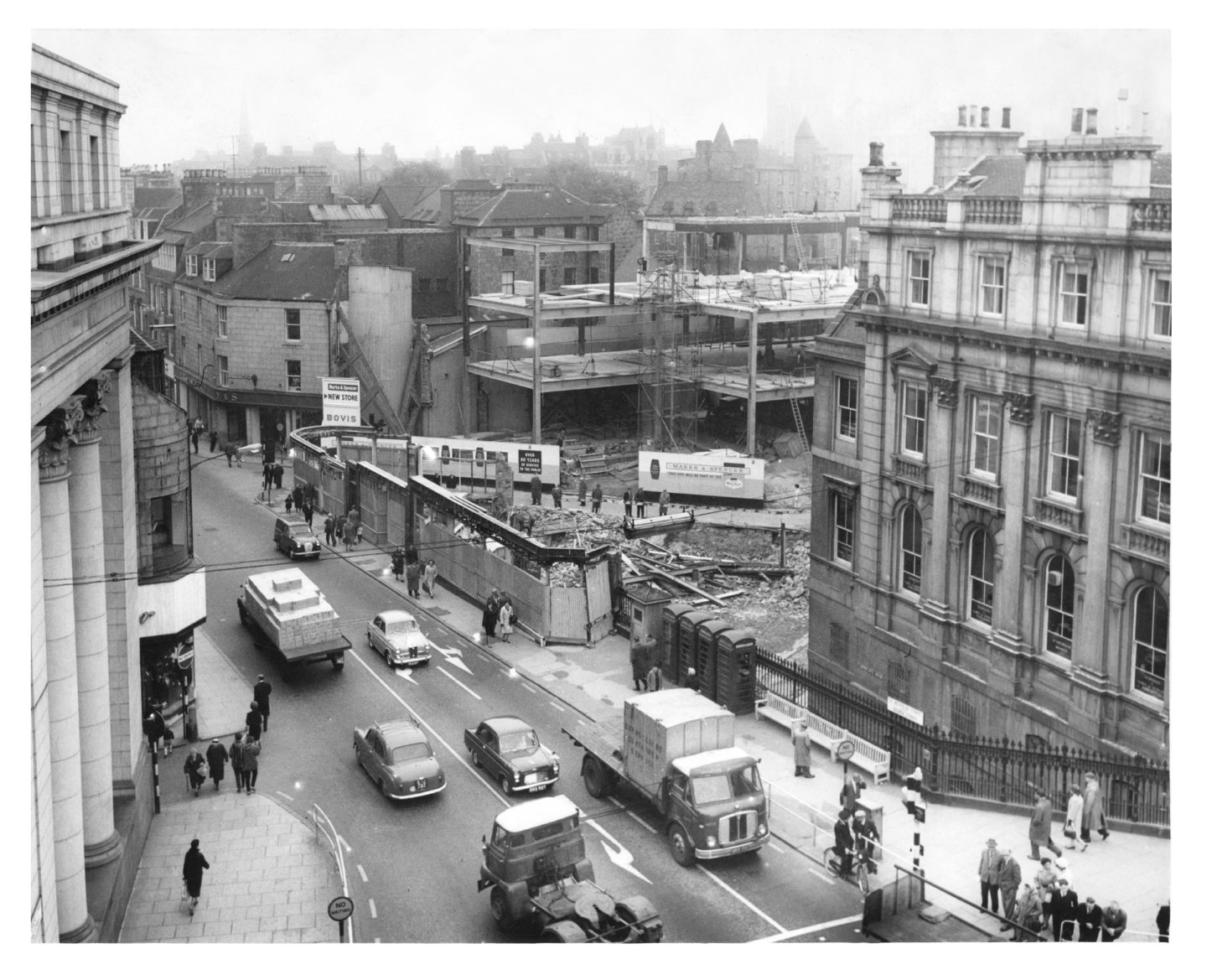

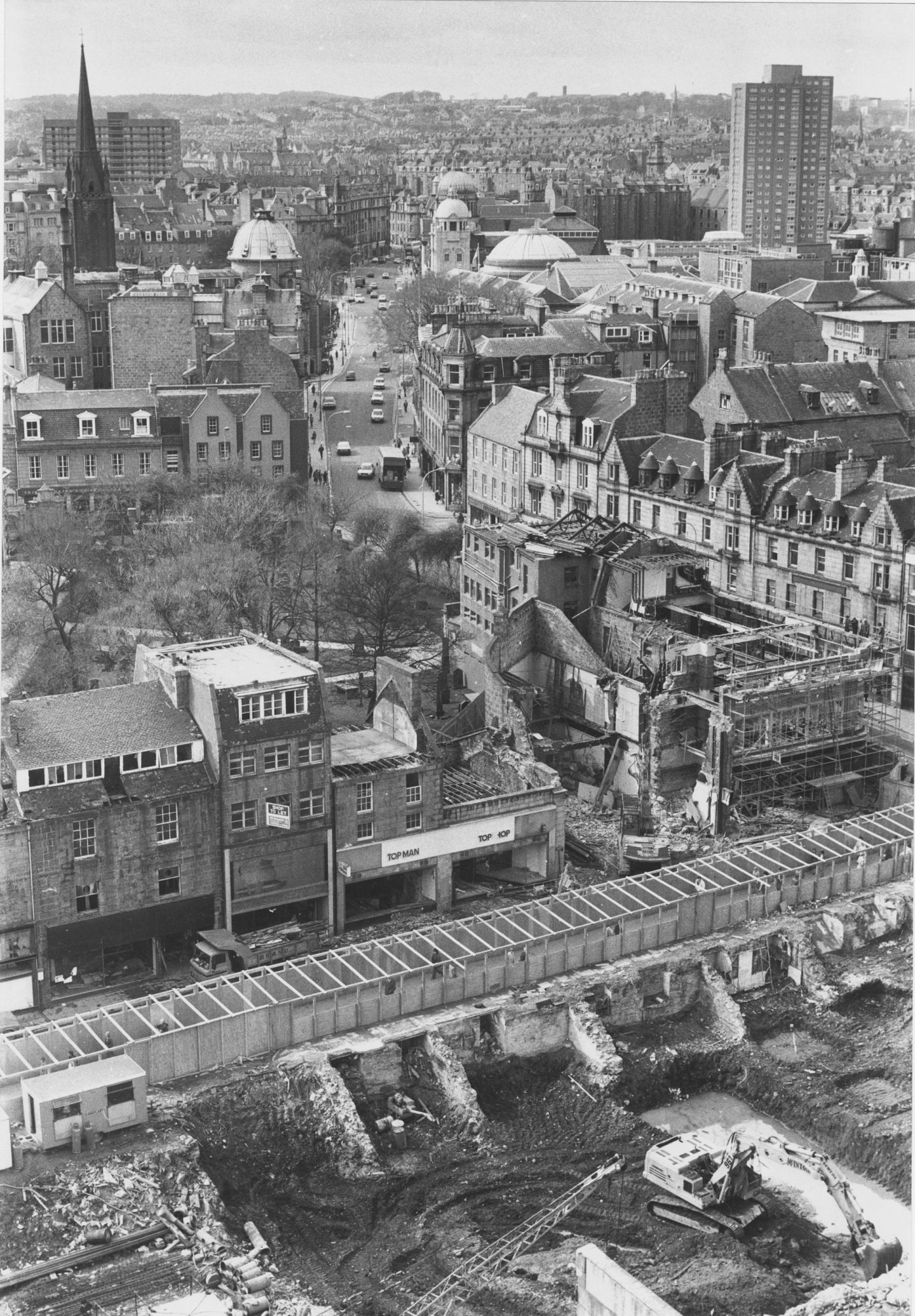

Agreement was reached over the redevelopment of St Nicholas Street, and in October 1982, the demolition began.

Mr Taylor of city architects Thomson, Taylor, Craig and Donald, said: “I’ve been involved with this project now for 18-and-a-half years. This is the light at the end of tunnel.”

Buildings were taken down brick by brick, starting at Upperkirkgate.

Over the coming months and years, the tired ghosts of Victorian and Georgian architecture were gone, along with St Nicholas Street as Aberdonians knew it.

In its place, the St Nicholas Centre rose; there were still shops on either side, but they were covered, the open thoroughfare was gone.

The new mall opened in October 1985, but still the arguments continued over the future of George Street.

Traders pleaded for an eleventh hour reprieve as decisions leaned towards demolition.

St Nicholas Street: Going, going, gone by 1985

It was a topic that dominated debates at the Town House, with to-ing and fro-ing between opposition parties continuing into 1986.

Eventually, councillors voted 16 to 10 to back plans for a new shopping mall.

Administration members had warned that backing out would only cause further “stagnation in Aberdeen”.

But the Liberal opposition said their views reflected the citizens of Aberdeen who, like the shopkeepers, did not want the city’s heart ripped out.

But modernity won over sentimentality, and the demolition began.

Some shops were lost to make way for the Bon Accord Centre, other traders simply gave up the fight, unable to compete with the chaos of construction.

The rise and fall of the mall

George Street shopkeepers who survived the “three-year slump” felt positive about the opening of John Lewis in 1989 and the Bon Accord Centre the following year.

It was hoped the development would bring shoppers back and revitalise the area.

But ultimately, the malls took shoppers off the streets.

Long-established businesses and a way of life were consigned to the history books.

The glorious Reid and Pearson, MacMillan’s ‘doll hospital’, Isaac Benzies (later Arnotts) with its posh tearoom, and the Rubber Shop all disappeared through the shopping mall developments.

At their peak they were undeniably successful – in the 1990s, shopping was a hobby, not just a necessity.

But in recent times, with austerity, a recession, oil downturns, a shift to online shopping, a pandemic and now a cost of living crisis, the malls across Scotland suffered too.

Little over 30 years since the Bon Accord Centre opened, it has of late been facing the same questions about its future that people asked about St Nicholas Street in the 1960s and ’70s.

The destruction of St Nicholas Street and George Street was the biggest development in Aberdeen since the construction of Union Street, but was it also the most short-sighted?