The so-called ‘bouley bashers’ were once the scourge of Aberdeen’s highways and byways tearing through city streets in ‘souped-up’ cars.

A long and sweeping road, Aberdeen’s picturesque Beach Boulevard and esplanade was an illicit racetrack for generations of boy racers.

Careering along the beachfront in beat-up old cars – and latterly, modified performance cars – earned young drivers the nickname bouley bashers.

Aberdeen’s infamous boy racing subculture even made national headlines, such was its notoriety.

‘Brands Hatch by the seaside’

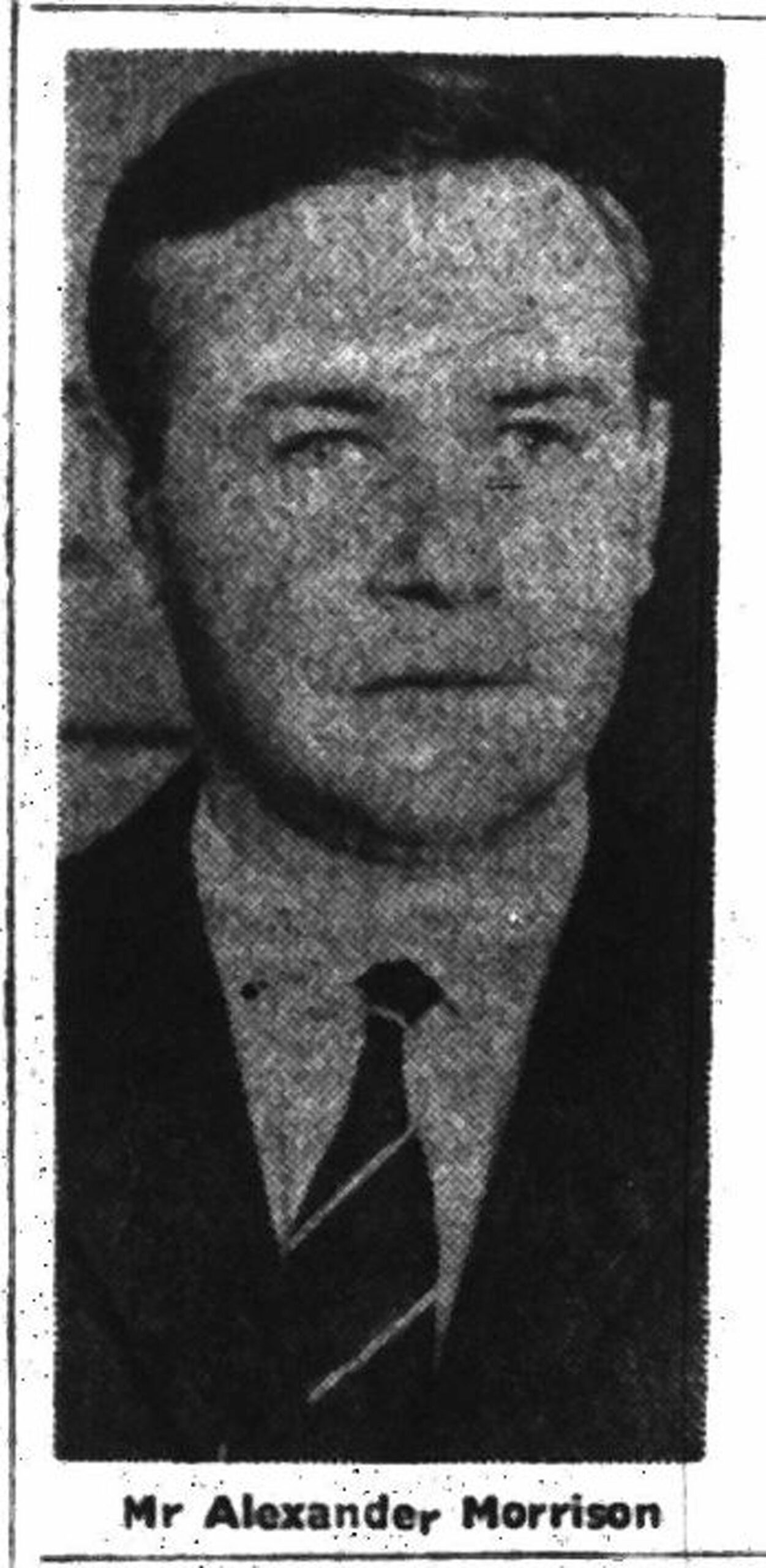

But racing along Aberdeen’s boulevard wasn’t a modern phenomenon.

Almost as soon as the Boulevard was completed in 1960, creating a city-centre circuit, it attracted racers.

Continuing into the ’70s, it became a place for Aberdeen’s answers to Formula 1 drivers James Hunt and Niki Lauda to race motorbikes, cars, smoke and socialise with friends.

In fact, furious residents dubbed the boulevard ‘Brands Hatch by the seaside’, comparing the antics to that of Brands Hatch – the former F1 racing circuit in Kent.

The long, hazy summer days of summer 1972 were anything but pleasant for Boulevard council flat tenants.

Taking their concerns to the council, residents explained how “young men in mini cars and on motorcycles flew down at high speeds and caused bedlam” on a daily basis.

And there was no let-up. Even at night they could hear “squealing tyres” as racers rounded corners and at midnight revved engines outside their doorways.

Residents wanted reduction in rates

Tenants wanted a reduction in rates to compensate for the antisocial behaviour, “lack of privacy, prostitutes and wine-drinkers” they had to put up with.

But their plea was refused. Aberdeen Valuation Appeal Committee chairman David Henderson said although the council “sympathised very greatly” there was no evidence to devalue the flats.

It wasn’t just Bouley bashers shattering the peace.

Residents’ spokeswoman, the formidable Mary Duncan, claimed young children playing with dolls and roller-skates were so loud tenants couldn’t hear their TVs.

Between the boy racers and neighbourhood kids, Mary lamented the dire lack of privacy, and added: “I cannot change my stockings in my own living-room because of people passing the window.”

Even Mary’s window screens weren’t enough to deter nosy motorists.

Next-door neighbour Alexander Dunbar said the speed limit was meant to be 30mph, but vehicles “flew past at between 50mph and 60mph”.

Bouley bashers got worse in 1970s

Come 1976, and in the world of F1, James Hunt snatched victory in the Championship, rounding off a dramatic season of racing in which rival Lauda nearly died.

But back in Aberdeen, despite complaints and Grampian Police’s “constant watchdog duties” at the Boulevard, nothing quelled the Bouley bashers’ need for speed.

That summer was “worse than ever” according to residents who were literally losing sleep over the problem.

Chief Constable Alexander Morrison agreed the issue was becoming worse.

Even stepping up patrols had no effect because drivers slowed down when they saw police then raced off again.

He added: “There is no doubt those drivers concerned quickly observe a police presence and this adds to the difficulty of detecting offenders.”

But in 1977, police officers thought they had the answer: VASCAR.

A forerunner to speed cameras, the Visual Average Speed Computer and Recorder would capture boy racers without the giveaway panda car.

‘These motorists are killing themselves’

But still, this didn’t put the brakes on the Bouley bashers.

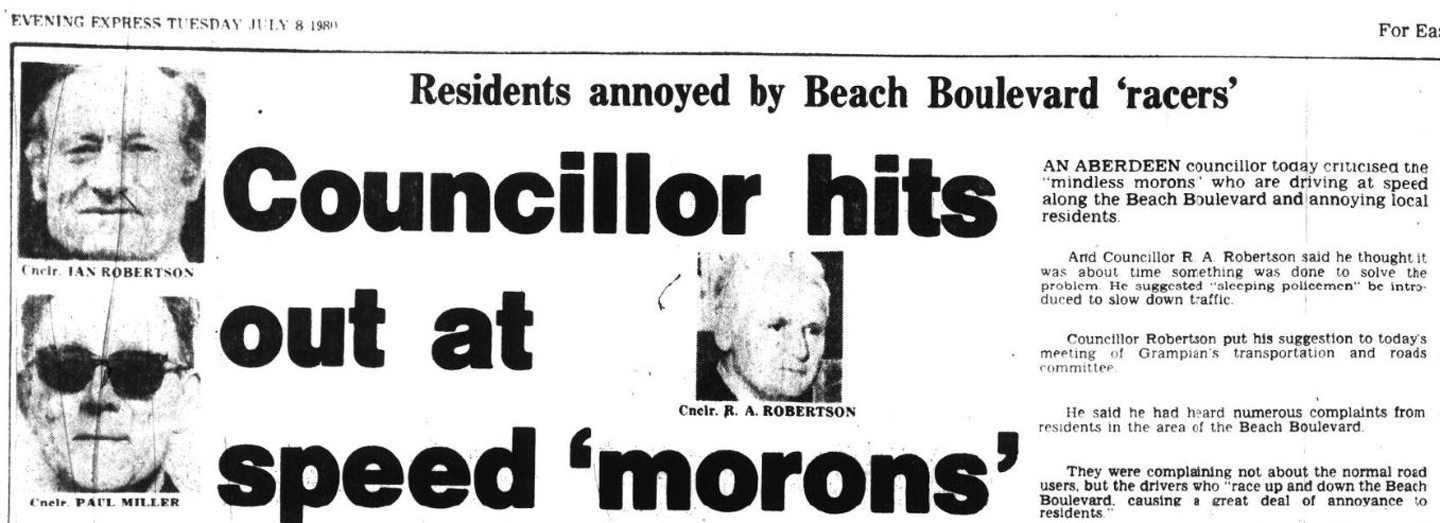

By 1980, there was a multi-agency approach to dealing with the indefatigable Granite city speedsters.

At a Grampian transportation and roads committee meeting, Councillor Robert Robertson suggested installing speed bumps on the boulevard to deter speed “morons”.

He said police had done their best but couldn’t patrol round the clock.

Councillor Paul Millar agreed and added: “These motorcyclists are so young, so inexperienced that they are killing themselves.”

But committee chair Ian Robertson vetoed the proposal and said sleeping policemen were inappropriate for a public road.

Just months later, a motorcyclist was fined £150 after being clocked at 76mph on the Beach Boulevard.

By the late ’80s, long-suffering tenants had had enough.

Mr Campbell, of 86 Beach Boulevard, said: “We are subjected each night to a cross between the Monte Carlo Rally and Brands Hatch as young drivers vie with each other to travel at the greatest speed and cause the most noise.

“The police seem unable or unwilling to tackle the problem head on.”

Deafening exhausts and sound systems

Despite years of misery, it was only going to get worse in the 1990s. Urban regeneration of the beachfront created new hangouts for the Bouley bashers.

The expansive entertainment complex car parks were ideal meeting spots, for young drivers from across the region.

And the huge park and ride car park at Bridge of Don was another top spot for the city’s young cruisers.

Performance cars began to replace the beat-up old motors that used to crash around the Boulevard.

While there was still speeding, boy racers would also gather to socialise and admire each other’s cars.

Turbochargers, gigantic spoilers, body kits, custom paint jobs and deafening exhausts were the order of the day.

While fellow petrol-heads may have been impressed by the modified motors, local residents and Grampian Police certainly were not.

Not content with roaring revs and hissing dump valves, many of the cars were also fitted with big subwoofers to achieve the optimal level of booming music.

This, in addition to the cars flying up and down the boulevard, was met with utter disdain.

£200,000 speed cameras installed

The stand-off between authorities and bouley bashers continued, and so did the incidents.

A spectacular crash on the Boulevard in 1996 saw four people taken to hospital when a Vauxhall Nova SR rolled over a Ford Sierra and landed on its roof.

And it was no longer just the police and council concerned.

In 2003, as the Bannermill area was regenerated for housing, the housebuilders themselves became concerned.

They feared anti-social behaviour would devalue property and even offered to help pay for deterrents.

But the bouley bashers were one step ahead – in the days before social media sites they used a website forum to co-ordinate activities in the city.

The site provided tips on evading the law, as well as details of high-speed exploits.

It called itself a “board dedicated to cruisers in the north-east” and boasted 480 registered users who posted over 30,000 entries.

Bannermill residents said some locals were taking matters into their own hands, photographing number plates and throwing eggs at cars.

But in June 2003, Police hailed a £200,000 new CCTV system, which detected 13 offences in the first fortnight.

The cameras followed traffic improvements at the beach by Aberdeen City Council.

Traffic-calming measures included new signals, crossing facilities, speed tables, widened pavements, a 20mph speed limit and parking.

Controversial anti-social behaviour act brought in

Still, the bouley bashers weren’t abated; police received 266 calls about their behaviour in 2004.

The council considered more radical measures like residents-only barriers and even closing the boulevard altogether.

But things accelerated significantly when the Scottish Government passed the Anti-social Behaviour (Scotland) Act 2004.

Under the act, which aimed to curb disorder, a pioneering ‘dispersal zone’ was introduced at the Boulevard.

Police could ban groups of perceived troublemakers for 24 hours, with any banned person returning facing a £2,500 fine.

It was a controversial move, but admitting “conventional enforcement had failed to eradicate a problem for 30 years”, Grampian Police said it was a last resort.

First conviction under act overturned

In spring 2005, police were granted permission to extend the dispersal zone after a 53% drop in reported incidents of anti-social behaviour.

And in November, the first people were convicted under the anti-social behaviour act.

The pair said they were “shocked and disgusted” as they had only been driving up and down the Boulevard.

They claimed neither to be speeding or playing loud music, and vowed to appeal.

The men’s conviction was overturned at Aberdeen Sheriff Court in December, although they still vowed to take their case to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

The dispersal zone experiment ended, but in 2006 issues continued around the beach and neighbouring streets.

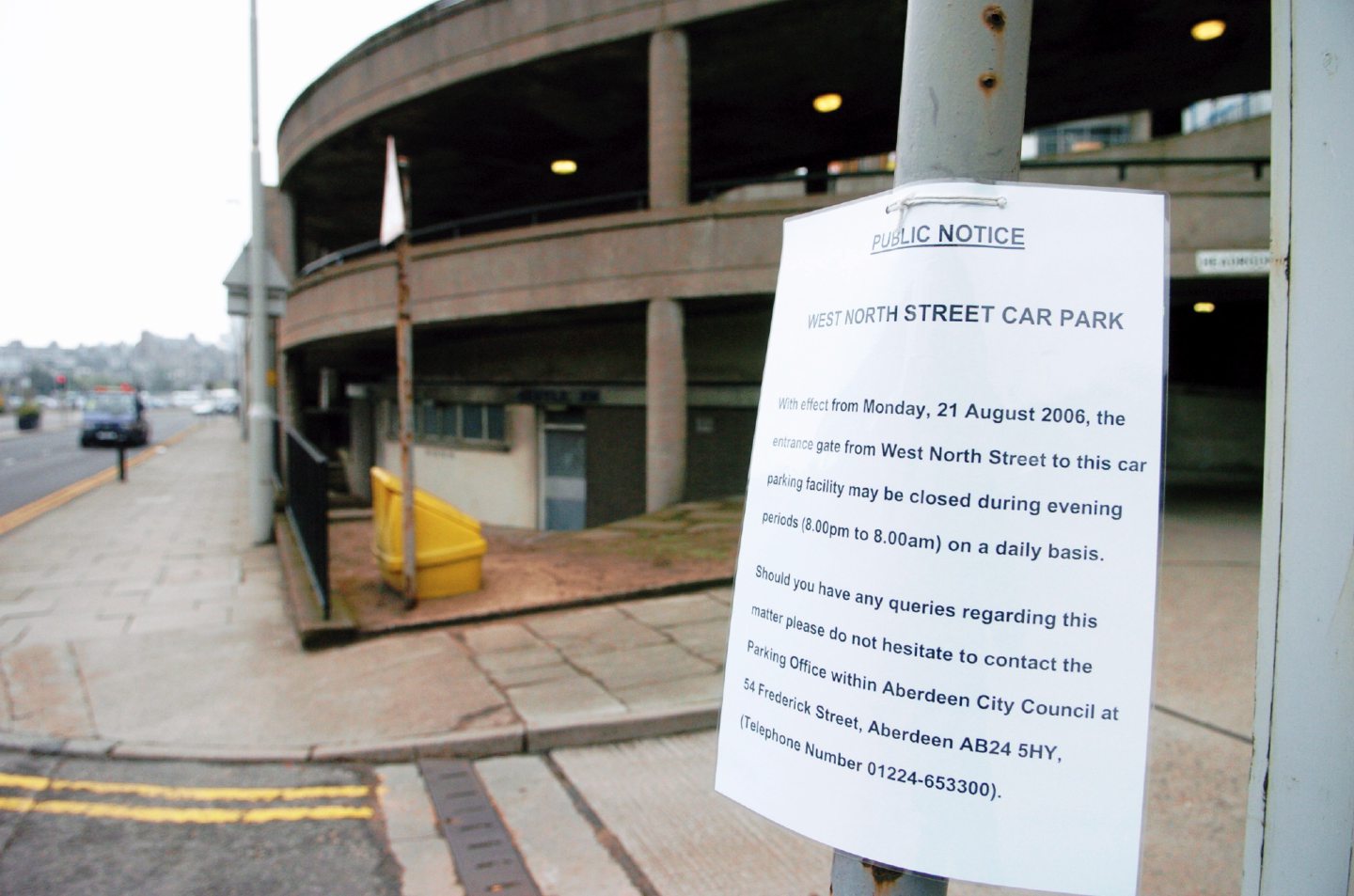

Police and the council were forced to padlock West North Street carpark which was being used as part of the boy racers’ nighttime racing circuit.

And in the year that followed, police seized 50 vehicles from anti-social drivers and a further 329 received warnings.

Beating the bouley bashers

The tough approach with ASBOs made national headlines; then-first minister Jack McConnell praised Aberdeen for its crime crackdown.

He hailed the city for embracing the powers to stop crime and give residents “respite from disorder”.

Come 2011, police were back on the Boulevard beat, carrying out high-visibility patrols.

But Chief Inspector Kevin Wallace and his team took a holistic approach, engaging with both drivers and the community.

His team were credited with ‘beating’ the bouley bashers, ending decades of misery for residents.

Such was the achievement, he and his officers received the Chief Constable’s Excellence Award.

Reflecting upon the success after his retirement in 2018, Ch Insp Wallace said: “We set about doing something about it and, over time, managed to make a change.”

Although, the bouley bashers haven’t quite been consigned to the history books.

In recent months, there have been complaints about boy racers tearing up Holburn Street.

And in June, a large, unofficial car meeting at the Beach Boulevard saw more than 100 cars and drivers enjoy a catch-up.

But while the majority followed the rules and enjoyed the “buzz” of the event, police said there was still some anti-social behaviour that resulted in some vehicles being seized.

More Past Times stories

Gallery: Take a drive down memory lane with these old photos of garages in Aberdeen

Conversation