They were the holiday party who travelled from southern England to the north of Scotland 50 years ago this month.

And, when they checked in at the Esplanade Hotel in Oban for a summer excursion, they could never have imagined that so many of them would never return home.

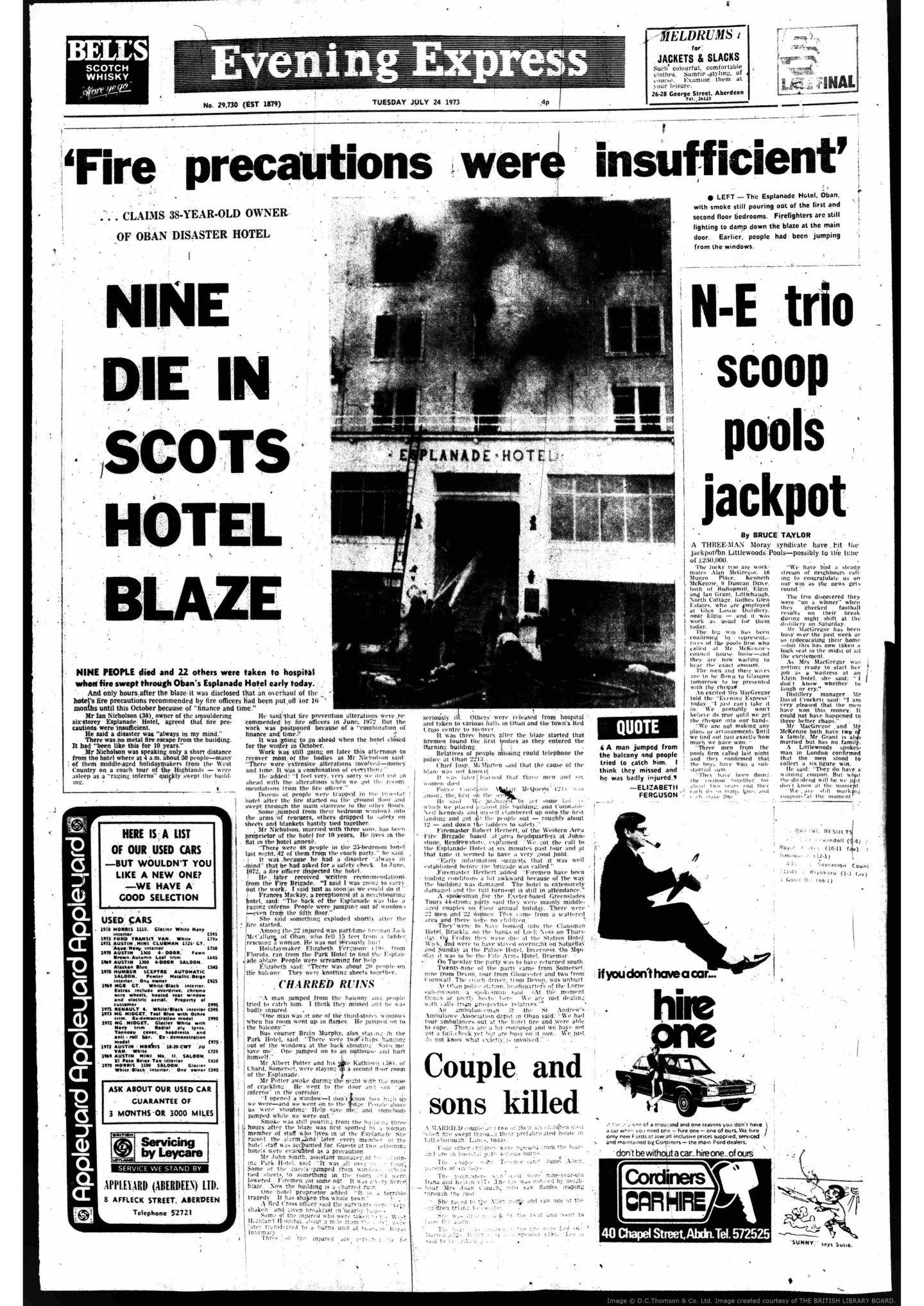

Yet, in the early hours of the morning of July 24 1973, a terrible conflagration broke out inside the premises on the seafront.

It rapidly transformed the scene into one of horror, chaos and dreadful loss of life.

A total of 42 people from Cornwall, Devon and Somerset who were on a Greenslades Coaches tour were staying in the hotel, as were two families.

A sailor spotted the Esplanade Hotel fire

The proprietor, Ian Nicholson, was in the process of implementing new safety measures within the building, but that couldn’t prevent fire sweeping through the multi-storey property as guests slept in their beds.

And, although the alarm was raised when a sailor on his yacht in Oban Bay saw a glow in the first floor reception area of the hotel at about 3.15am, and sent one of his crew ashore to notify the authorities and also sounded his fog horn, it was too late for some.

In the hours and days that followed, it was confirmed that 10 people, five men and five women, had died as a result of the blaze.

Donald Malloch was among the firefighters who attended the incident and spoke later about how the tragedy had accelerated moves to change existing hotel regulations.

He said, on the 40th anniversary of the disaster in 2013: “It all happened so quickly. It really was a sort of blur and you try to forget about it.

“The hotel was converted into flats, but if I go down the lane at the side, it is hard not to think about it because it was the worst fire I had dealt with in my time”.

Victims had little chance to react

The people who perished amid the flames were: Mrs Margaret Bolt, Exeter; Miss Ruth Davis, Bristol; Mrs Joan Humphries, Miss Dorothy Govier and Mr Hubert Brimble, all of Clevedon; Mr Peter Hallet and his wife, Jean, Bridgwater; Mr Albert Clarke, Bathwicke; Mr Thomas Jones, Yatton; and Mr John Clark, Exmouth.

The latter was injured in the fire and died two days later in the Western Infirmary from pneumonia, paralysis, fractured cervical vertebrae and a fractured femur.

This was one of the worst peacetime death tolls in history, but it could have been even worse. A couple from Coventry who were with their six-year-old son managed to escape when the man jumped onto a roof that projected out from the building and his wife dropped their child to him before jumping down herself.

More than 20 others were taken to hospital, suffering from shock and smoke inhalation.

The Evening Express covered the story in detail on July 24 and revealed that an overhaul of the hotel’s fire precautions, recommended by officers, had been delayed for 16 months “until this October because of finance and time”.

It also stated how Mr Nicholson had admitted the safety measures were “insufficient” and that a “disaster like this was always in my mind”, especially given there was no metal fire escape from the building, which had been in this condition for 10 years.

Inquiry ruled nobody was to blame

However, in October 1973, after hearing six days of evidence, the jury at a fatal accident inquiry into the Oban fire returned a verdict finding that the cause of the blaze was, on the balance of probability, a dropped light somewhere in the foyer/reception area.

It found that no fault or negligence could be attributed to the hotel staff and all reasonable improvements had been made.

But the verdict added the fateful words: “The jury find that all reasonable precautions were in hand and it was a tragic coincidence, which no one could have foreseen, that after the building had stood safely for close on a hundred years, it should have been destroyed with this grievous loss of life a mere 10 weeks before it was to close for the implementation of the full recommended precautions.”

There was praise for station officer Joe Simpson, a plumber who was in charge of the part-time fire personnel in Oban, for the bravery and professionalism with which they had tackled “this exceptionally severe fire with great determination and ability”.

The jury made three formal recommendations; that all fire appliances should be equipped with pocket radios; that the chief officers responsible for the GPO, police, fire and ambulance services in Oban should meet as soon as possible to review their response to dealing with emergencies; and that the procedure for testing escape ladders, laid down by the Home Office, should be reviewed to ensure that the ladders were strong enough to deal with potential emergencies in the future.

Outcome was no comfort to bereaved

In the aftermath, Mr Nicholson said that he felt the jury had reached “a very fair verdict” and described their recommendations as “very good”.

Yet, mystifyingly in the circumstances, Mr Robert Herbert, firemaster of the Western Area Fire Authority, said he was “delighted the Oban boys have come out on top”.

These glib words will have been absolutely no consolation to the holidaymakers who eventually returned to England without so many of their family and friends.