The allure of Balmoral forever enchanted Queen Victoria, making an indelible impression on the monarch – so much so, that Victoria left her own mark on the Aberdeenshire estate through a series of cairns.

Although deemed “unsuitable for the presence of a court”, Victoria was utterly charmed by Balmoral.

She found her trips to Deeside beguiling, and reveled in the informality of the wilderness and “frankness of the people”.

Victoria was always reluctant to depart her beloved Balmoral.

While there, she and Prince Albert could come and go as they pleased. They climbed Lochnagar, stalked deer, slept in huts by Loch Muick and went boating.

In 1852, Albert bought Balmoral and commissioned Aberdeen architect William Smith to design a new residence to replace the old castle.

Victoria wrote in her diary that Balmoral was her paradise, adding “every year my heart becomes more fixed here!”

Queen Victoria helped build first Balmoral cairn

She marked the purchase of Balmoral by building a cairn – a memorial built from a mound of stones.

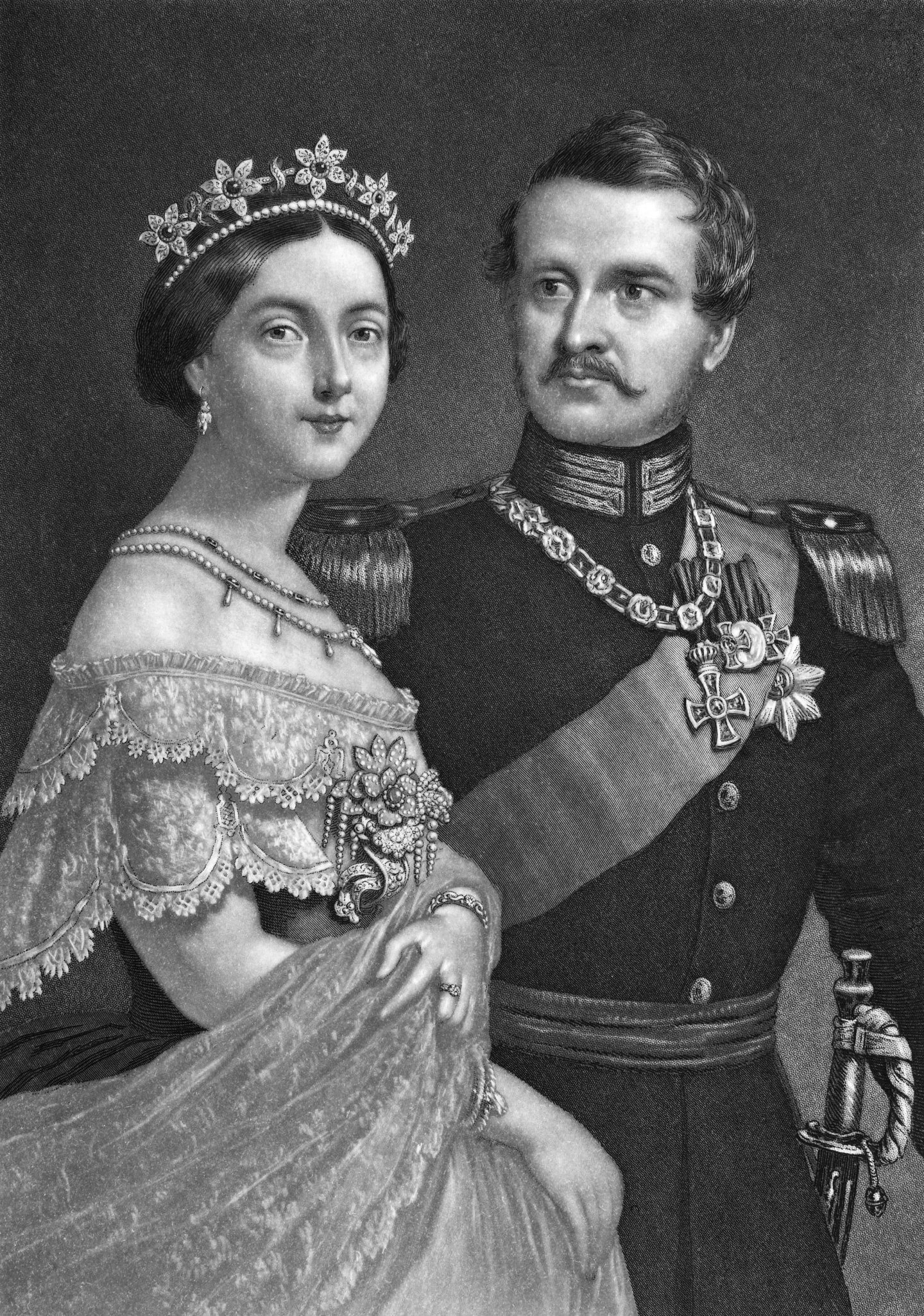

We usually think of Victoria as a regal widow, enveloped in grief and black robes in her latter years.

But the enthusiasm and vigour of her earlier reign is reflected in her deep affection for Balmoral and the freedom it gave her.

Queen Victoria started building the Purchase Cairn with her own hands when the family returned to Balmoral – as estate owners.

On October 18 1852, the royal family climbed to the summit of Craig Gowan, a hill overlooking Balmoral.

The large cairn was shaped like a haystack, completed by the royal family and estate workers, before Prince Albert laid the final stone.

Queen Victoria wrote in her diary: “I placed the first stone, after which Albert laid one, then the children, according to their ages.

“All the ladies and gentlemen placed one, and then everyone came forward at once, carrying a stone and placing it on the cairn.

“At last when the cairn, which I think is seven or eight feet high, was nearly completed, Albert climbed up to the top of it, and placed the last stone, after which three cheers were given.

“This took about an hour during which the piper Angus McKay played, whisky was drunk and merry reels danced on a stone opposite.”

1858: Princess Royal’s Cairn

It was the first in a long line of royal relics built in the years that followed to mark significant family events.

Queen Victoria was behind 14 of the 16 at Balmoral; the remaining two were commissioned for Queen Elizabeth’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012.

Victoria and Albert had nine children – four boys and five girls – born between 1840 and 1857.

When their eldest daughter, also called Victoria, married Prince Frederick of Prussia, the queen marked the occasion with a cairn.

Great importance was put on betrothals – most royal marriages were motivated by politics, prestige and duty rather than love.

And Queen Victoria was keen to establish a pan-European dynasty.

Of all the marriage cairns, Victoria and Frederick’s was the most grand, perhaps because she was the Princess Royal.

But also maybe because she was doted on by Victoria and Albert, who were devastated to see her leave for Europe.

Her cairn sits atop Canup Hill in Glen Gelder, but unlike the others is cut from semi-dressed granite, with a more formal appearance.

It takes the form of an obelisk with a carved sphere on top, bearing the inscription: “Prince Frederick William of Prussia, the Princess Royal of England, married January 25th 1858.”

1862: Princess Alice’s Cairn

The subsequent marriage cairns are more rustic.

Another reason could be that all were constructed after Prince Albert’s untimely death in 1861, a tragedy Victoria never recovered from.

Princess Alice’s marriage to Prince Louis of Hesse-Darmstadt on July 1 1862 was greatly overshadowed by her father’s death some eight months previously.

Alice had to wear black mourning clothes before and after the ceremony, and Queen Victoria, herself deep in mourning, said it was “more of a funeral than a wedding”.

Nevertheless, the queen wanted to mark the occasion with a cairn.

Apt, as Alice shared her mother’s love of Balmoral; she was said to be at her happiest when visiting tenants on the estate.

1863: Prince Edward’s Cairn

The cairn commemorating Prince of Wales, Albert-Edward (later King Edward VII), is not at Balmoral, but neighbouring Birkhall.

The property was given to Edward by his parents, and the cairn is located on the scenic Coyles of Muick.

Edward had a reputation for debauchery, and cared little for boring and rainy Balmoral.

Victoria commissioned the cairn in 1863 to remember her eldest son’s marriage to Alexandra, Princess of Denmark, on March 10.

No doubt she was relieved that he had settled down and appeared respectable.

1866: Princess Helena’s Cairn

The next child to wed was Princess Helena, and an article from August 2 1866 reported the construction of her cairn.

The memorial marked Helena’s betrothal to Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein the previous month.

A number of tenants and servants of the estate met on Craig Gowan under the instruction of Queen Victoria, to build a cairn.

“A pleasant and merry day was spent, and the health of the lately married couple was drunk amid hearty Highland cheering”, the account said.

1871: Princess Louise’s Cairn

When Princess Louise married on March 21 1871, there was similar celebration at Balmoral.

She too enjoyed her time spent in Deeside, and was a talented Highland dancer.

On the occasion of her union to John Campbell, the Marquess of Lorne, the estate tenants presented Louise with a necklace of Scottish pearls and matching pearl and diamond earrings.

Princess Louise conveyed her gratitude to in a letter saying she would treasure it as one of her most valued gifts “coming from kind friends” she always associated with “dear Balmoral”.

A popular princess, the wedding was marked up and down the country, and at Balmoral tenants built a cairn and had a bonfire.

1874: Prince Alfred’s Cairn

The marriage of Prince Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh, to Maria Alexandrovna of Russia also sparked jubilation in Deeside.

A huge celebration was held at Balmoral for the servants, tenants and surrounding community in January 1874.

An account of the party reads: “A cairn 22 feet high was erected on the hill of Rise. A monster bonfire, upwards of 20 feet in height was lit, darkness having set in.

“Two pipers played several Highland airs in fine style during the burning of the fire.”

1879: Prince Arthur and Leopold’s cairns

The building of Prince Arthur’s Cairn to mark his marriage to Princess Louise Margaret of Prussia was another community effort in 1879.

With an audience of dignitaries and tenants, the royal family laid the first stones.

Similarly, the whole royal family gathered to witness the completion of Leopold’s Cairn in 1882 on Craig Gowan.

It commemorated the marriage of Prince Leopold of Albany to Princess Helen of Waldeck.

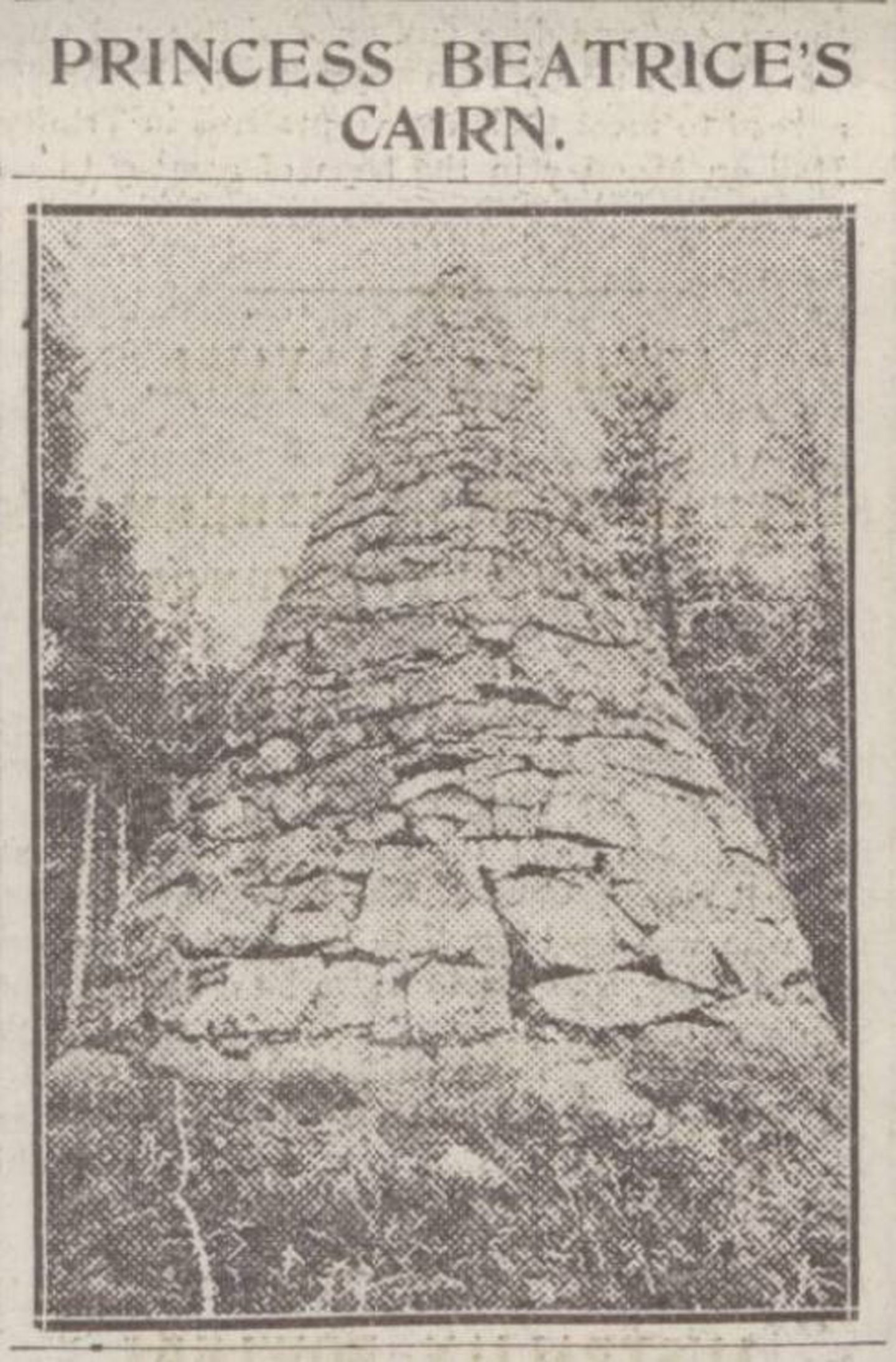

1885: Princess Beatrice’s Cairn

The last of Victoria’s children to marry was Princess Beatrice, whom the queen had not wanted to leave.

After the death of Albert she wanted her youngest daughter to remain as her companion.

But Beatrice fell in love with Prince Henry of Battenberg, eventually persuading Queen Victoria to allow her to marry.

On the day of her wedding at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, celebrations took place at Balmoral.

A newspaper account read: “During the last fortnight large numbers of workmen have been engaged making a walk to the top of the Craig at the back of Balmoral Castle, for the purpose of getting up material to build a cairn as a memorial of the marriage of the Princess Beatrice.”

1862: Prince Albert’s Cairn

By far, the most majestic cairn built at Balmoral was to honour the memory, life and legacy of Prince Albert.

He died on December 14 1861 aged just 42 years old from typhoid fever, devastated, Queen Victoria spent the rest of her life shrouded in grief.

And the following year she commissioned a grand pyramid of dressed granite as a token of her everlasting love.

She wrote in her diary that it was to be built at 35ft tall on top of Craig an Lurachain so “it could be seen all down the valley”.

On August 29 1862 Queen Victoria laid the first slab.

One of the inscriptions chosen by Victoria for the cairn stirred some controversy among the Free Church community as it was chosen from her prayer book and not the Bible.

It read: “He, being made perfect in a short time, fulfilled a long time. For his soul pleased the Lord; therefore hasted He to take him away from among the wicked.”

Dr Candlish described the inscription from the Wisdom of Solomon as an “offence to the Bible which Scotland loves”.

But other leapt to the broken-hearted queen’s defence calling Candlish “over-zealous” and “fiery-tempered”.

The queen found much sympathy locally, and her personal inscription was a poignant tribute to the man she adored on the estate she loved.

It read: “To the beloved memory of Albert the great and good Prince Consort. Erected by his broken hearted widow Victoria R. 21st August 1862.”

1878:Ballochbuie Forest Cairn

After Albert’s death, she continued to holiday at and improve her “paradise” Balmoral.

Ballochbuie Forest is one of many scenic forests around the estate, famous for its pines, which Queen Victoria was keen to conserve.

She bought the forest and erected a cairn on Creag Doin with the inscription: “Queen Victoria entered into possession of the Ballochbuie, 15th May, 1878. The bonniest plaid in Scotland.”

Her decision to buy the forest is hailed as an early act of woodland conservation, with some trees dating back 400 years.

Legacy of Balmoral Cairns

Guests were said to be “astonished” by the sheer number of curious cairns scattered around the estate, which she leased in 1848.

But she simply said she had a great liking for memorialising friends and events in this way.

Two further cairns commissioned by Victoria were The Duchess of Kent’s Cairn – Queen Victoria’s mother – near Sgor an h-lolaire.

The other was a tribute to her companion and favourite servant at Balmoral, John Brown, but the cairn was removed by her son Edward who disliked the man.

Even in the decades and centuries after her death, it was said the return of different generations of the Royal Family to Balmoral each autumn stirred “a wealth of reminisces” of Queen Victoria.

Dotted across the breathtaking landscape, cairns and rustic tombstones continue to commemorate Queen Victoria’s loves, losses, events – even her dogs – who otherwise would have been forgotten in the mists of time.

More Past Times stories

The hidden fog house waterfall and 6 other secrets of Bennachie

Photos of Aberdeen at war seen in colour for the first time

Remembering Archaeolink, the living history park in Aberdeenshire

Conversation