Just six pieces of paper stood between life and death for Henry John Burnett, the last man hanged in Aberdeen — and Scotland — 60 years ago.

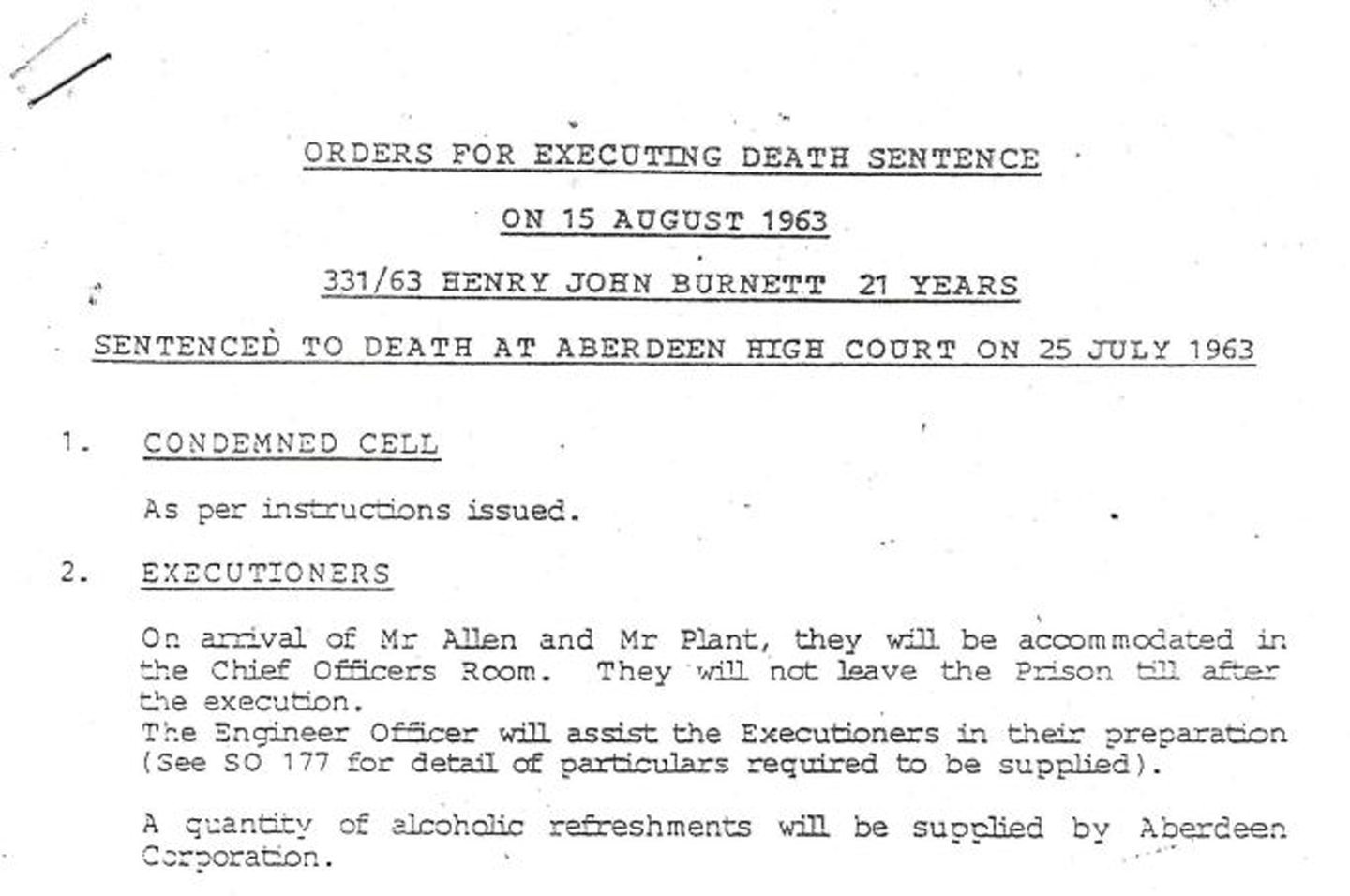

The last days and moments of Burnett’s life are outlined in a simple, typewritten document, entitled “Orders for executing death sentence”.

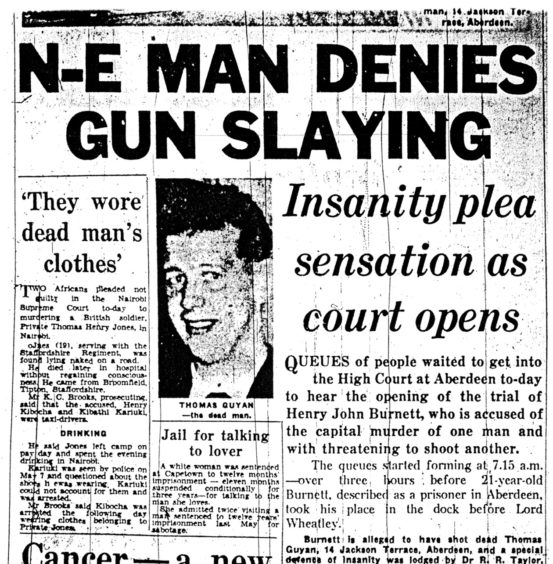

Burnett was sentenced to death at the High Court in Aberdeen on July 25 1963 for murdering seaman Thomas Guyan in an impulsive crime of passion.

And at 8am on August 15 1963, he was put to the gallows and hanged.

He was just 21 years old when his life was extinguished at Craiginches Prison.

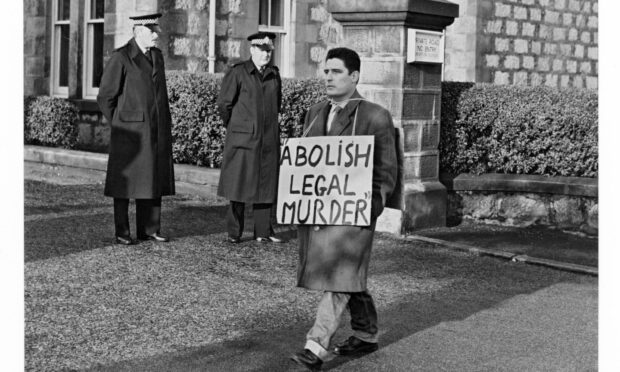

But the hanging of the last man in Aberdeen wasn’t the ghoulish spectacle of mediaeval times – Aberdonians were outraged.

Now 60 years on, the last days – right down to the last moments – of a death sentence that should perhaps never have happened, have been revealed.

Love triangle ended in tragedy

Burnett was guilty all right. He shot dead merchant seaman and love rival Thomas Guyan on May 31 1963.

Some months before, Burnett had fallen in love with Guyan’s wife Margaret, a colleague.

Margaret was estranged from her husband who worked away for long periods, and in May 1963, she moved into Burnett’s rented room on Skene Terrace.

He had a history of severe mental illness and suicide attempts, and pressed Margaret to divorce Guyan.

Fearful she would leave him, he would lock her in the flat in fits of jealousy.

Burnett arrived with shotgun

On May 31, Margaret met Guyan at the White Cockade Bar in Torry seeking a divorce.

But instead, they decided to give their marriage another go.

Returning to Skene Terrace, Margaret told Burnett the news, furious, he held a knife to her throat.

She fainted, and thinking he’d killed her, Burnett dashed from the flat to his brother’s house where he grabbed a shotgun.

Meanwhile, Margaret escaped, making her way to her grandmother’s flat at 14 Jackson Terrace where her husband was waiting.

Ninety minutes later, her lover appeared.

Guyan opened the door to see Burnett — who he had never seen before — holding a shotgun.

‘I’ve got ye noo’

Burnett said: “I’ve got ye noo”, and blasted Guyan in the face, killing him instantly.

Burnett reloaded the gun and frogmarched Margaret into the street where he commandeered a car at a nearby petrol station.

With Margaret held hostage, he took off into the countryside, stopping twice on his way: once to ask directions to Peterhead and again to get a light for his cigarette.

He pulled over at Ellon and police arrived almost immediately.

He pulled over at Ellon and police arrived almost immediately.

Burnett told the two constables who arrested him: “It’s me you want.”

The attack on Margaret, the killing of Guyan, the car theft and police chase all took place within a frenzied two hours.

‘He is a person of psychopathic personality’

When Burnett’s trial began on July 23 1963, the defence lodged a special plea of not guilty on the grounds of insanity.

The court heard compelling evidence from three psychiatrists declaring Burnett insane at the time of the crime – and his trial.

As well as suicide attempts, he’d previously spent time in a mental hospital.

Burnett was examined in prison by consultant psychiatrist Ian Lowit, who had seen him some years before.

Lowit told the trial: “He is a person of psychopathic or extreme immature personality and in that sense may be regarded as not fully responsible for his behaviour.”

His assessment was supported by two other psychiatrists, but the court and judge Lord Wheatley were suspicious of their sympathetic approach.

His mother Matilda wept in the dock recalling previous incidences of his erratic behaviour.

And as she left the dock, she cried out to her son: “Henry, it’s okay ma loon. It’s okay.

The trial lasted only three days and it took just 25 minutes for the jury of 10 women and five men to reach a verdict.

Guilty of murder and sentenced to death by hanging.

Petition against death sentence

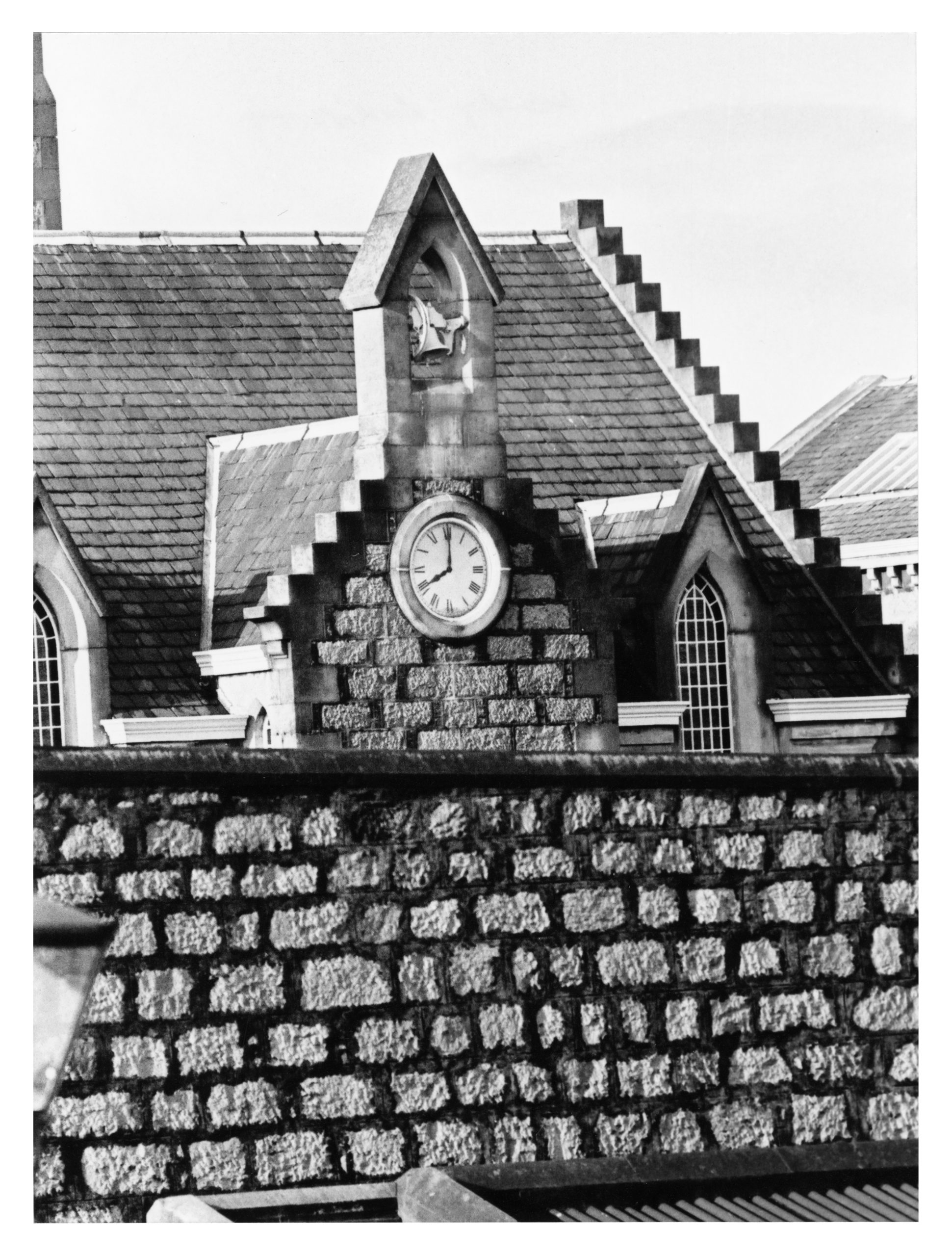

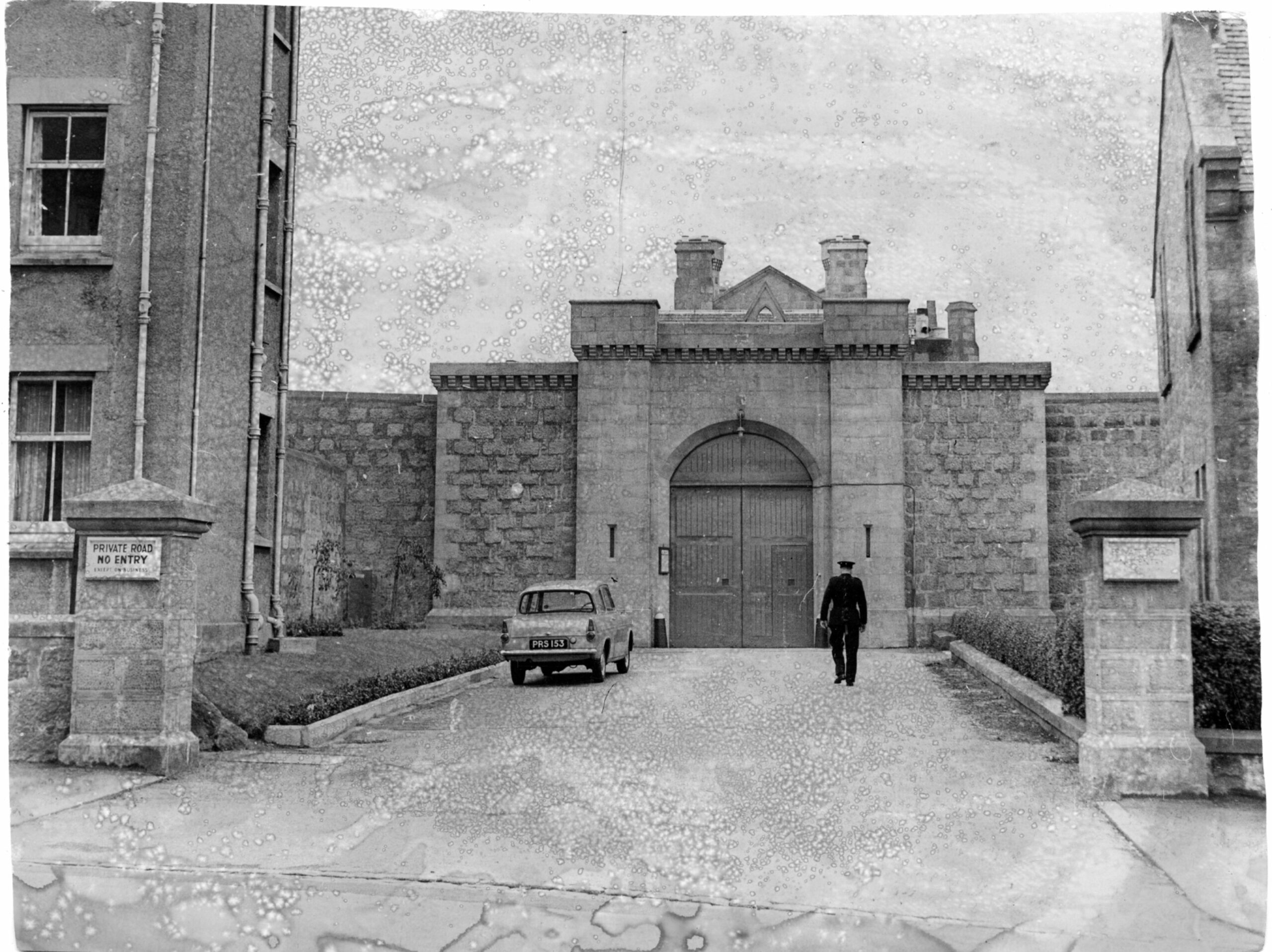

It was to be the first hanging in Aberdeen since 1867 and the only execution in Craiginches’ history.

Executions were fairly rare in Scotland, and this crime didn’t bear the hallmarks of the sort of abhorrent, premeditated capital murder that usually ended in a death sentence.

Aberdonians were in uproar, and a petition was started pleading for his reprieve.

The first person to sign it was the victim’s mother Jeannie Guyan.

She said: “I don’t want revenge. The last thing I want is that he should die. His death won’t bring my Tom back.

“It was a terrible thing he did, but he’s only a laddie.”

Burnett’s parents set up signing stations in the city where people could add their signatures to the plea.

But it fell on deaf ears, there was to be no reprieve.

Orders for Execution

Burnett seemed convinced the sentence would be overturned.

But the Orders for Execution were drawn up by governor Mr Angus.

It may just be six pieces of paper, but it carries the weight of a man’s life within its faded words.

The document outlines the days leading up to Burnett’s hanging, including a first-hand account by principal prison officer Allan Grant.

The papers give instructions to the prison officers “employed on death duties” in the condemned cell.

Two guards had to watch him at all times, but Grant said “Burnett was a prisoner who related well to staff”.

They were told to “keep suitable books” in the cell for use by the prisoner, but newspapers weren’t allowed.

The instructions continue: “Watchdog officers should try to keep the prisoner’s mind occupied with talk when he is not reading or sleeping. Cards, draughts and other games will be permitted.

“Prisoner is permitted 20 cigarettes or 1oz of pipe tobacco, daily.”

Burnett’s meals were brought to his cell, and he was allowed one hour’s exercise morning and afternoon in the open air.

‘That was the last farewell’

Officers had to fill in the ‘occurrence book’ detailing when Burnett went to bed, his activities and visitors.

They also had to note down any remarks that could have a bearing on the case.

An extract on one particular day read “10am – prisoner read books and was quite cheerful”.

The night before his execution, Burnett’s own clothing was put in the condemned cell – except a collar or tie.

Grant said: “On the day before Henry John Burnett was hung, his lover Mrs Guyan was taken to the prison to visit Burnett.

“That was the last farewell, I know, I was the officer on duty at the gate on that day.”

Chaplain said Burnett was remorseful

He goes on to explain how the cell was wood panelled with private toilet facilities and concealed doors so as not to reveal the prisoner’s last walk.

As it happened, Burnett never went through the hidden doors.

Grant’s account revealed that the drop platform and hooks on the roof had been fitted incorrectly during a refurbishment.

Rather than entering the execution chamber from the cell, Burnett had to go onto the landing where the magistrates were standing, then straight onto the platform.

All the prisoners ate breakfast before those in ‘A’ hall were moved to the other side and locked up at 7.30am.

This was done to ensure no prisoner could identify or see the hangman or any witness to the hanging.

The executioners arrived in advance. And so did solemn crowds outside the prison.

Other staff present were the prison governor, medical officer, chaplain, chief officer, engineer officer, nurse officer and two prison escorts.

At 7.30am Burnett was offered ‘a stimulant’ – likely a nip of alcohol.

And at 7.57am the magistrates were taken to the execution chamber before Burnett was escorted out.

In one hand the officers held onto a loop of rope, with the other they held Burnett’s sleeves.

It was the final human touch in the last moments of his life.

Chaplain Reverend John Dickson said Burnett was “very sorry” for his actions and had convinced him the crime had been on impulse.

Rev Dickson held up the cross of Iona, the last thing Burnett saw before the hood went on.

At 8.01am executioner Harry Allen opened the trapdoor, and Burnett was dead.

Burial was undignified end

Afterwards, the magistrates returned to the governor’s office where they too were offered something to steady their nerves.

The two officers who escorted him to the platform were excused from duty for the rest of the day.

Burnett was placed in a coffin and buried in his own clothes, while all his letters and papers were put in the furnace.

His grave was dug in the recess between the pit room and the staff room toilets.

It was an undignified end for a man who was mentally unwell, and considered as much of a danger to himself as he was to others.

The stunned masses outside the prison stood in silence throughout the execution.

But after the hanging, the 500 people outside made their outrage known.

History was made on fateful day

In his account of that day, Grant explained: “After the hanging at 8am, staff were permitted to go for their own breakfast.

“On arrival at the front gate they found it almost impossible to pass the crowd of protesters at the end of the prison drive shouting ‘murderers’ and other forms of verbal abuse. Few staff went home for breakfast that day.

“The crowd waited for a notice to be displayed on the front door of the prison gate giving details of the time the prisoner was executed.

“There was never any notice published.

“The crowds eventually dispersed, the staff returned to their duties.”

After the execution, it was business as usual for the staff and prisoners at Craiginches.

But history was made in Aberdeen that day when Henry John Burnett was the last man hanged, signalling the end of capital punishment in Scotland.

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

Conversation