Highland doctors warned there would be more deaths on the A9 if the government failed to make “significant” safety improvements in 1973.

The Scottish Council of the British Medical Association (BMA) wrote to the Scottish Office at Westminster highlighting members’ grave concerns about safety on the A9.

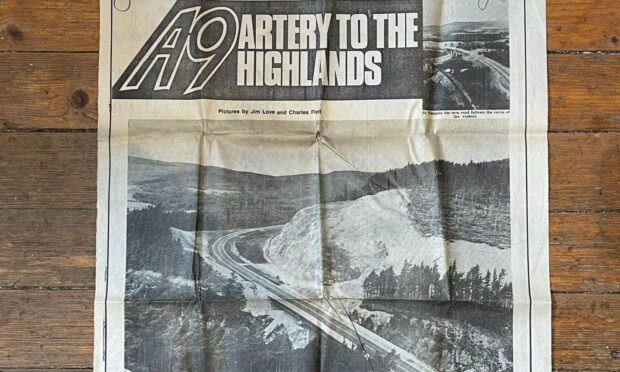

In October 1973, work was to began on the biggest civil engineering project ever seen in Scotland – the new A9.

But months before construction was to start, rural doctors warned the proposed improvements weren’t good enough to prevent increasing deaths.

Fewer doctors per mile on A9 than any other trunk road

The Scottish arm of the BMA issued the stark warning about the increased danger of death on the A9 due to the remote nature of medical care in the Highlands.

It explained there were “fewer doctors per mile on the A9 than on any other main trunk road in Britain”.

In writing to the government, Inverness County Council, Perth County Council and the Scottish Tourist Board the BMA sought to relay the concerns of rural GPs.

Dr Stephen J Hadfield, the Scottish secretary to the BMA, said he was expressing the views of the doctors routinely called to accidents on the A9.

He said their fears were “endorsed by others who live in surrounding counties and use the road in their journeys”.

He added that “special considerations of safety” should be applied to the A9 “because the reduced availability of doctors and hospitals must lead to increased fatalities arising from accidents”.

Police and doctors united in call for better A9 improvements

Dr Hadfield said police and ambulance services in the Highlands echoed doctors’ concerns, and were already trying to improve their own communications to save lives.

Together they urged for “all possible steps be taken for the improvement plan for the road to prevent or reduce accidents”.

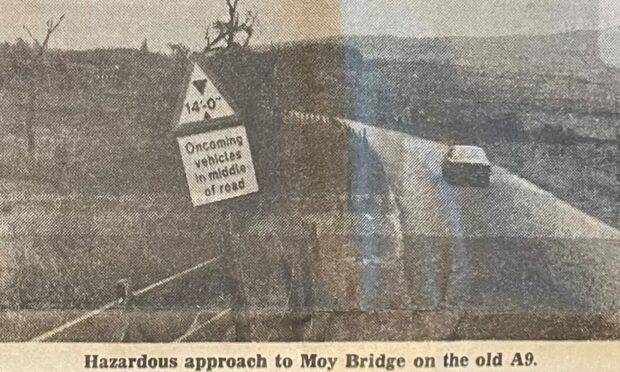

The trunk road had been nicknamed the killer A9 due to the number of fatalities between Perth and Dingwall.

In March 1972, Scottish Secretary Gordon Campbell announced a £10,000,000 single-carriageway improvement scheme.

But plans to rebuild the 137-mile stretch between Perth and Cromarty were criticised for not going far enough.

Communities and commuters wanted the A9 dualled, and warned that it would become a “death track” if it remained a single carriageway.

Doctors’ concerns over ‘third lane’ proposal

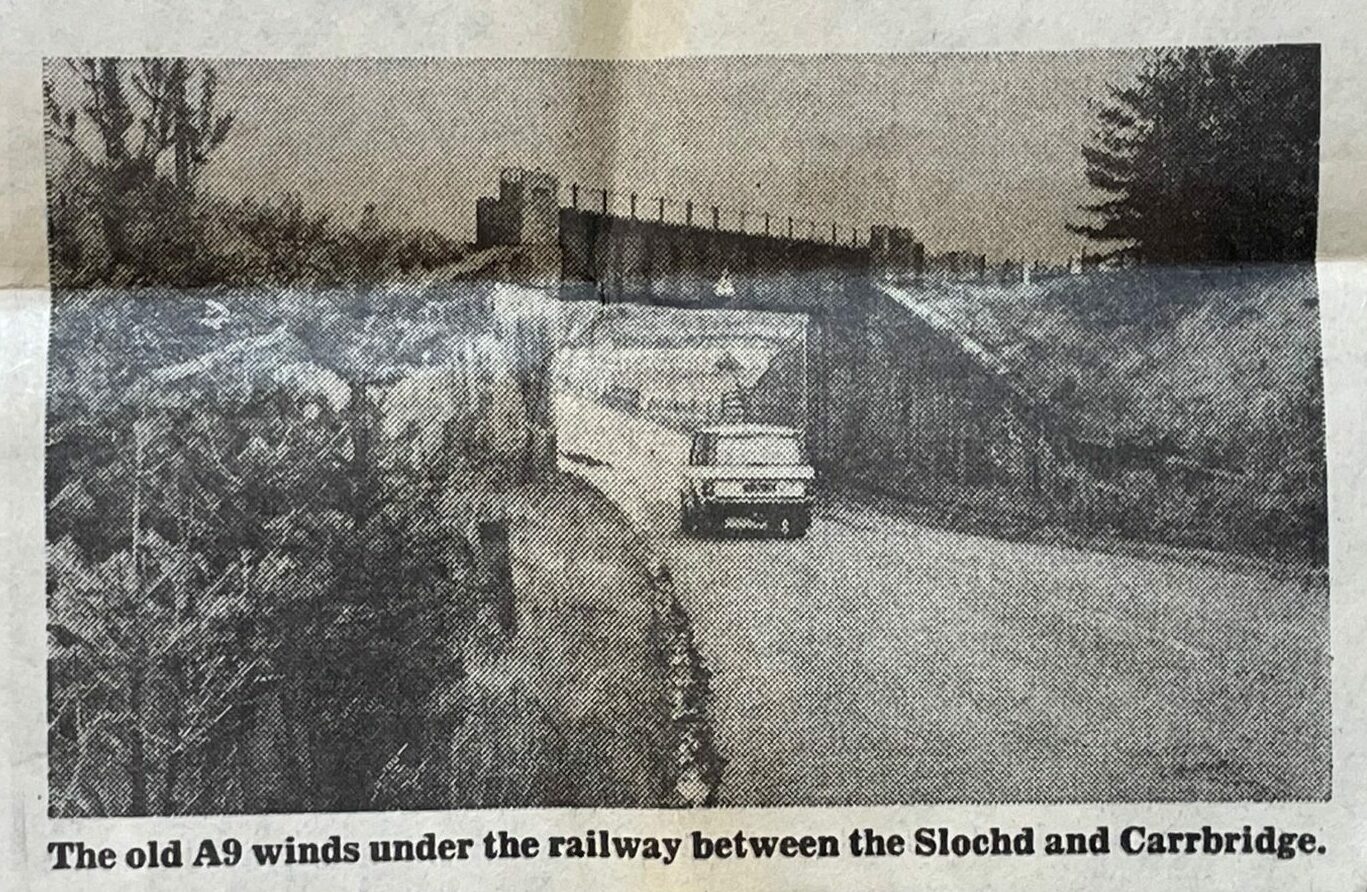

Dr Hadfield explained: “The road is already carrying heavy loads of traffic at all times, including tourist traffic, common market traffic with exceptionally heavy vehicles and heavy construction traffic, all of which has stepped up recently.

“All these tend to contribute to a high accident rate.”

Doctors were particularly concerned about proposals put forward by the Scottish Development Department to introduce a third lane on A9.

The idea was that it could be used by alternate flows of traffic, and was nicknamed “the kamikaze lane”.

Dr Hadfield said: “The council [of doctors] do not believe that the decision to have a three-lane road, with the middle section alternating between north and south-bound lanes for overtaking eliminates the danger from certain drivers.

“The first priority should be given to considerations of safety.

“The present proposals do not appear to be sufficient to eliminate or substantially reduce the dangers.”

Crash victims ‘faced 60-mile journeys by ambulance’

He said in the event of a collision, casualties either had to be taken to Perth Royal Infirmary or Bridge of Earn hospital depending on the nature of injuries, or to Raigmore Hospital in Inverness.

Dr Hadfield added: “Perth and Inverness are nearly 120 miles apart, and people injured in accidents are often faced with up to 60 miles by ambulance.”

In response to doctors’ concerns, Conservative MP Gordon Campbell, Secretary of State for Scotland at time, said safety was a “very high priority” in reconstructing the A9.

He pointed out that the new road would “not have the tight bends which constituted the main hazard”.

But he also suggested the concerns were out of proportion, adding that the accident rate on the A9 “did not depart appreciably from the national average”.

It was a remark that was not welcomed by doctors.

Dr Hadfield retorted that “statistics could be made to mean anything”.

Opposition spokesman on Scottish Affairs, Edinburgh MP Gavin Strang, was also unimpressed with Gordon Campbell’s response on A9 safety.

Labour MP said UK government was ignoring Scotland

Speaking at a Labour Party meeting in Inverness in September 1973, Strang said the Scottish Office must be forced to change their “derisory and irresponsible plans” for the notorious A9.

He said the government was planning to spend £650 million on a third airport for London near Maplin, but “were not prepared to spend even a tenth of that figure on the A9”.

He criticised Mr Campbell for preparing to back the project for the south-east of England, but not “to even draw up plans for a dual carriageway to the capital of the Highlands”.

Mr Strang added: “No government since the war have shown such a lack of interest in Scotland.

“The government pay lip service to a regional policy, but the cabinet are clearly devoting more time to Concorde, the Channel tunnel and Maplin than to the whole of Scotland, Wales and the regions.”

He even issued a direct plea to Scottish Tory backbench MPs to “stop this monstrous further concentration of economic activity in the south-east of England” and put the interests of Scotland before London.

Plans for the airport at Maplin were spectacularly scrapped after a government u-turn the following year.

But no more consideration was made to dualling the A9 from the money saved in cancelling the Essex airport project.

Conversation