It’s 100 years since the erection of a statue to the poet Lord Byron at his alma mater, Aberdeen Grammar School (AGS).

A century later, a small knot of people gathered at the statue to pay tribute once again to the great poet — and also to the small boy who laid the first wreath at his statue on September 14, 1923.

Thanks to the sleuthing of historical researcher Callum Stuart, the identity of that small boy and his moving story has come to light.

Callum spent a year at AGS, researching the role of former pupils in World War One.

The statue made its way into his mind, and being an ever-diligent researcher, he began to wonder about its history.

The story he uncovered grew arms and legs and gradually became infused with poignance and coincidence.

Byron’s statue was erected in 1923

The statue wasn’t erected until 1923, almost a full century after the great poet’s death at Missolonghi in Greece.

The fact that there were already statues to William Wallace and Robert Burns in Aberdeen prompted a Press and Journal reader to complain in a letter in 1892 that there was nothing to commemorate the world- renowned poet with a far greater claim to a statue in Aberdeen than Wallace or Burns.

There followed a great deal of discussion by the AGS board as to the merit of such a statue.

Callum said: “Many of the distinguished old gentlemen on the board said we’ve got a bust of Byron inside the school, why should we want one outside?

“Then there were disagreements about who had had the idea in the first place, while a subscription for it was raised in the late 1890s, and 250 people signed a letter to support the idea of a statue of Byron in Aberdeen.”

The vote narrowly scraped through

In the end, the school board only just approved it, by eight votes to seven.

“Imagine how stupid they would have looked if it had gone the other way,” Callum said.

Byron spent a year at AGS, in its previous incarnation at Schoolhill.

Designed by the King’s Sculptor, James Pittendrigh-Macgillivray, the bronze statue stands on a pedestal of Inver granite from Upper Deeside.

George Gordon Noel Byron was born in London in 1788, but with his father up to no good in France, was soon whisked north by his mother, Catherine Gordon of Gight in Aberdeenshire.

His father, known as Mad Jack, scored very highly in the recklessness and fecklessness stakes and when he eventually turned up at Catherine’s Queen Street lodgings he was sent on his way.

The family’s fortunes reduced, and Catherine and George moved to Broad Street — first coincidence, close to the site of the old Aberdeen Journal, later to become the P&J.

Byron learned the basics at Aberdeen Grammar School

George gained the rudiments of his education at AGS before he suddenly, and unexpectedly, inherited the baronetcy of Rochdale and moved to the ancestral home, Newstead Abbey in Nottinghamshire aged 10, as Lord Byron.

Byron himself said he was ‘born half a Scot, but bred a whole one.’

You can read more about Byron’s formative years here.

Callum didn’t stop his research at the history of the statue, and turned his attention to wondering who the young lad was who laid the first wreath at the statue on September 14 1923.

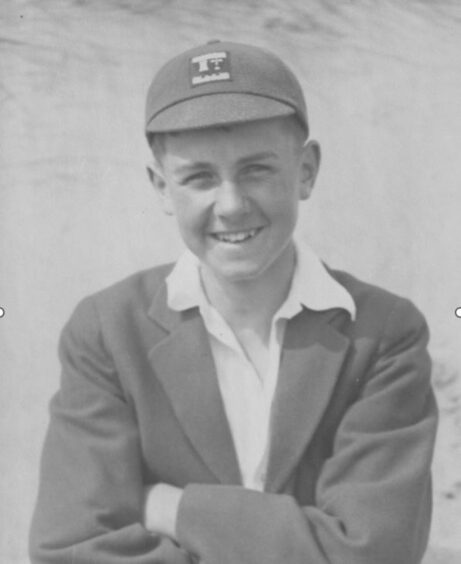

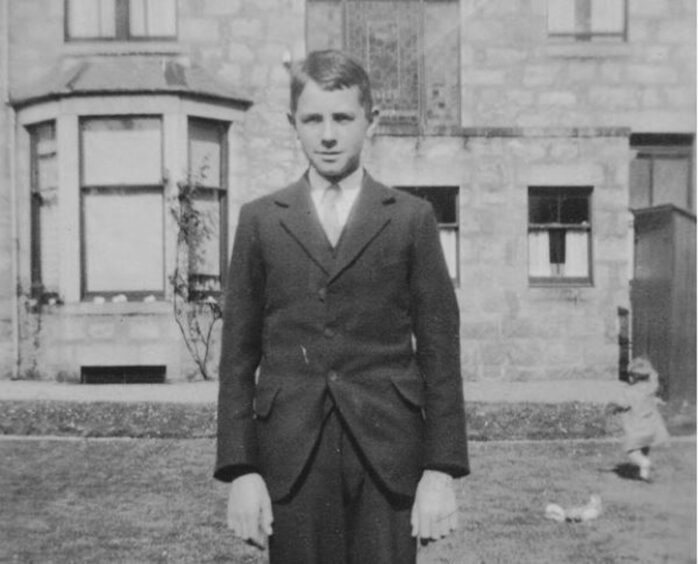

It turned out to be 10 year old George Theodore Robertson Watt, nominated for the honour by his peers.

The irrepressible Callum wondered why he was chosen. There must have been something about the young lad.

What Callum found out about George and his family revealed the extraordinary coincidence of a generations of a family steeped in, like Byron, words and poetry.

And tragedy, in the ultimate fate of young George, who died, like Byron in the Aegean, fighting for freedom in 1941.

Byron espoused the cause of Greek independence from the Ottoman empire, and such was his influence that it’s been speculated that had he lived, he might have become king of Greece.

Although Callum knew George was 29 at the time of his death, was unmarried with no descendants, he soon tracked down George’s nephew, Graham Watt.

Graham, emeritus professor in General Practice and Primary Care at the University of Glasgow, takes up the story.

“George Watt was the eldest son of Theodore Watt, secretary and treasurer of the AGS FP Club for 27 years, editor of its magazine for 39 years and the first of three generations of presidents of the club.

“George attended the school from 1918 to 1931, was active in the school’s 9th Wolf Club Pack and 17th Scout Troop, and was a prefect in his final year.”

Byron and George had something in common, Graham found out.

“Aged 11, George climbed Lochnagar with 4 family members and over 100 others for the unveiling of the Cairngorm Club indicator.

“Aged 15, Byron climbed it, with lots of stops, in 1803 while re-visiting the north-east and staying at Invercauld.

“Years later he would write a poem about ‘Dark Lochnagar’ and remember the mountain while overviewing the plains of Troy.”

George studied medicine at Aberdeen University, graduating in 1936, when he moved to work as an apprentice in general practice at Insch in Aberdeenshire.

Graham said: “After a house job at the Aberdeen Royal Maternity Hospital under Professor Sir Dugald Baird, he moved to hospital jobs in London and Sheffield to pursue a career in obstetrics and gynaecology.

“When war broke out, he joined the navy and was posted as a Surgeon-Lieutenant on HMS Wryneck, a minesweeper operating out of Alexandria in Egypt, with many voyages transferring troops across the Eastern Mediterranean.”

On April 27 1941, HMS Wryneck was attacked and sunk by German bombers, while evacuating British troops from mainland Greece.

“An eye witness told George’s parents that he had died instantly in the ship’s medical station.

“His resting place is a war grave in the Aegean Sea, midway between Greece and Crete.”

Graham added these sobering statistics: “My uncle George was one of 194 Aberdeen Grammar School former pupils who died in active service in World War II.

AGS sustained terrible losses

“Their average age was 27. Ninety-two were aged under 25. Most were single men.

“There were nine sets of brothers. In the school’s Roll of Honour, they are not just names or statistics but individuals with photographs and pen portraits of lives cut short.”

George Watt’s great niece Nuala is one of Scotland’s leading young poets with degrees in English literature at the Universities of St Andrews and Glasgow.

At the wreath-laying ceremony, she read out this moving poem of Byron’s.

So, we’ll go no more a roving

So, we’ll go no more a roving

So late into the night,

Though the heart be still as loving,

And the moon be still as bright.

For the sword outwears its sheath,

And the soul wears out the breast,

And the heart must pause to breathe,

And love itself have rest.

Though the night was made for loving,

And the day returns too soon,

Yet we’ll go no more a roving

By the light of the moon.

The inscription on the wreath laid by Graham and Nuala reads: ‘In memory of those who gave their lives fighting for freedom in countries other than their own.’

More like this:

Byron’s formative years in Aberdeen – did they make him mad, bad and dangerous?

A poetic odyssey to crumbling Gight Castle

Conversation