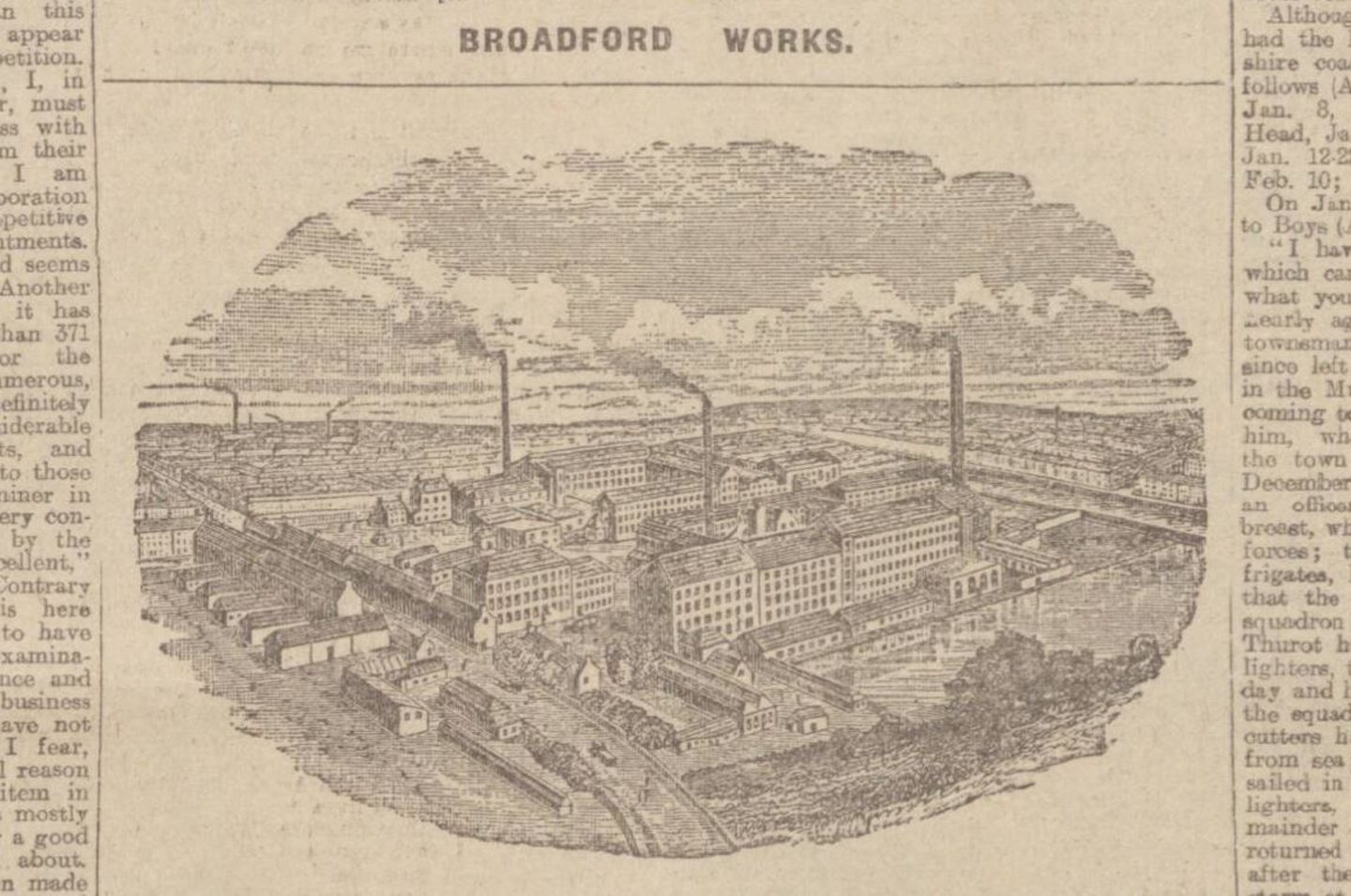

A textile manufacturing powerhouse in Aberdeen for nearly 200 years, Broadford Works once employed 3000 workers. But now its decaying brick buildings stand like forgotten tombstones to a lost industry.

Dating back to the time of the Napoleonic wars, Broadford Works was founded by the firm of Scott Brown from Angus when the Grey Mill opened in 1808.

It marked a seminal shift in how textiles were produced in Aberdeen.

Prior to the industrial revolution, wool, cotton and flax was spun by hand, before being handwoven into fabric.

The advent of steam power and machinery took textile production out of homes and sheds, and into vast mills and factories.

But it was a business that didn’t need to go looking for its troubles.

This is the history of Broadford Works, read on to find out how:

- How workers led one of the first mass strikes in the city against its greedy owners, in a landmark moment for trade unionism in the city

- How it fared when it was bombed by the Nazis in WWII

- And the impact of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on getting the site sold

Broadford Works at forefront of industry

When Scott Brown went bankrupt in 1811, the site was bought over by businessman, banker and MP John Maberly, who gave his name to the neighbouring street.

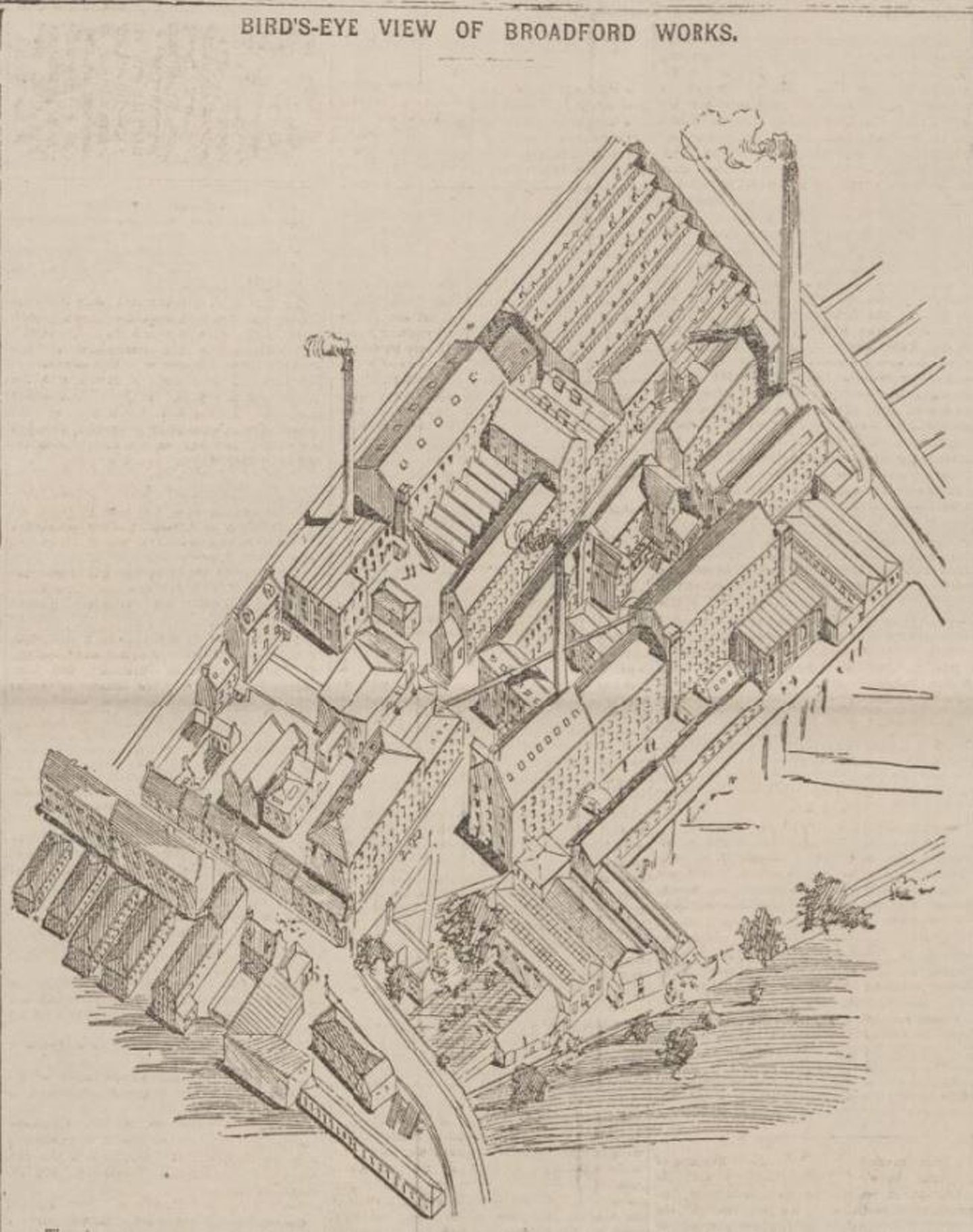

Demand saw the mill complex expand into several buildings on the site collectively known as Broadford Works.

Maberly oversaw the rapid development of the site and it was the first industrial premises in Scotland to have gas lighting installed.

The original Grey Mill was now flanked by spinning mills.

As technology improved bigger buildings were need to house the cutting-edge machinery.

And the works became Scotland’s second power loom linen weaving factory, helping to make Aberdeen a leading light in textile manufacturing.

One of Aberdeen’s biggest employers

Maberly went into partnership with London banker John Baker Richards, a fellow governor of the Bank of England, in 1825.

He was later declared bankrupt and the business was taken over by Richards and Co, who owned bleachworks at Rubislaw and Montrose, in 1832.

Richards quickly became one of the city’s biggest employers, and it is a name that remains synonymous with Aberdeen today.

But it wasn’t a happy workforce.

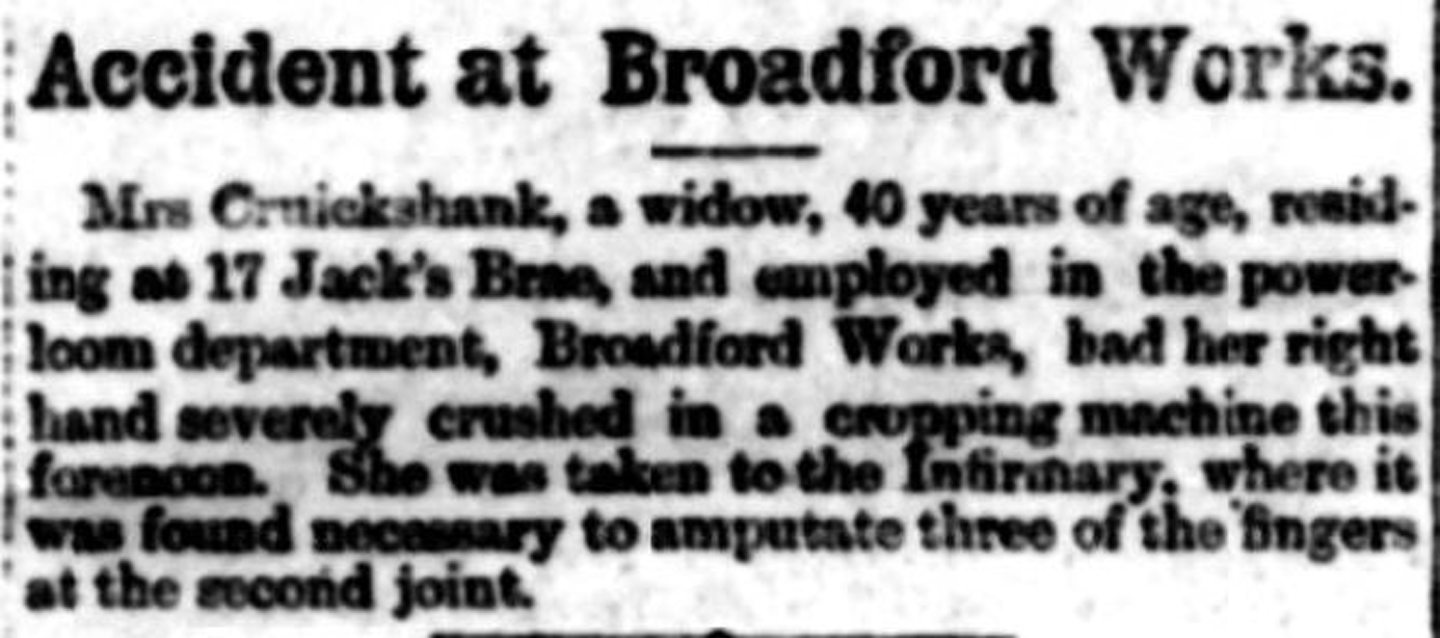

The conditions at Broadford Works epitomised the grimy aspects of working-class Victorian Britain.

It was loud, dangerous, dirty and physically demanding — for both men and women.

The EE and P&J were full of stories about workers’ limbs being crushed or severed.

When Richards put its profits before its people there was outrage.

Women workers fought against greed

In 1834, around 150 young women downed tools after being told to take a sixpence cut in their average weekly wage of six shillings.

The brave spinners and reelers banded together to oppose the greed and injustice from the works’ wealthy owners.

Taking to the streets they proclaimed they would no longer submit to “oppression and low wages”.

With financial support from fellow workers they managed to hold out on strike for five weeks.

When the women returned to work they lost the sixpence off their wages.

But it was the first time industrial action had been taken in Aberdeen and marked a landmark moment for trade unionism in the city.

Broadford Works, specialising in the linen trade, remained a huge employer.

By the 1860s, it had 2000 workers – most of whom were women — which remarkably accounted for nearly 5% of the population of Aberdeen.

Textile trade troubles hit Broadford Works

But it faced further financial misfortune, and the firm nearly collapsed in 1898.

Out of the blue, Richards suspended its payments and made workers redundant.

The news shocked business circles in Aberdeen and the wider linen industry in Scotland, because Richards was an established and respected brand.

A band of public-spirited individuals in Aberdeen formed a syndicate to save Broadford Works, such was its “utmost importance to the City of Aberdeen.”

After months of negotiating, an offer of £46,000 was accepted by the works’ trustees, and Richards became a public company.

Peaks and troughs in fortunes

Moving into the 20th Century, Richards experienced prosperity with government contracts to provide canvas and heavy lines.

But this was short-lived, and like many industries during the 1930s, Broadford nearly went bust during the Depression.

It came close to bankruptcy once again in 1933, but a new board of directors pulled it back from the precipice.

The directors, all local businessmen, focused on overhauling the business rather than expanding it.

Shares were offered to the public and the company prospered.

Richards was largely concerned in the production of heavier fabrics used for mailbags, sails and covers for railway wagons.

Come wartime, the works were struck during the infamous midweek blitz on April 21 1943.

Bricks were strewn everywhere when a mill was hit by Nazi bombs.

But press censorship during the war meant this could not be reported at the time so as not to damage morale.

And by the 1950s, it had its own research laboratory and a “weatherometer”, a device that could simulate weather.

Richards also took over three glove, clothing and hosiery companies in the city.

The ’60s saw Broadford Works diversify into the production of synthetic fibres for carpet manufacturing.

And in 1972 Richards split into subsidiaries producing industrial textiles, hosepipes and synthetics.

But the works were hit by industrial action again in 1978 when engineers operating automated machinery felt unskilled workers were closing the pay gap.

A short stay of execution

Richards continued to make acquisitions in the 1980s and ’90s, while still producing fabrics at Broadford Works.

As the sun was setting on the 20th Century, the sun was also setting on Broadford Works.

By 1998, the workforce was down to 450, and the firm fell into difficulties.

Bosses were keen to move away from the Broadford Works and eyed up a new site on the outskirts of the city.

But after five years of heavy losses, Richards fell into receivership in 2002 when a funding deal failed.

A combination of failing to sell Broadford Works, a £5 million shortfall in its pension scheme and a loss of trade after 9/11 was blamed.

Almost like history repeating itself, the firm was bought over by millionaire Aberdeen businessman Ian Suttie, and on December 23 2002, 150 jobs were saved.

With support from the city council, Richards moved to a new location in Granitehill Road in 2003.

But it was a short stay of execution.

The following November, the historic firm slipped in administration.

Just weeks before Christmas in 2004, workers were stunned when they turned up to the Northfield premises to be told the company was about to fold.

Decades of decay

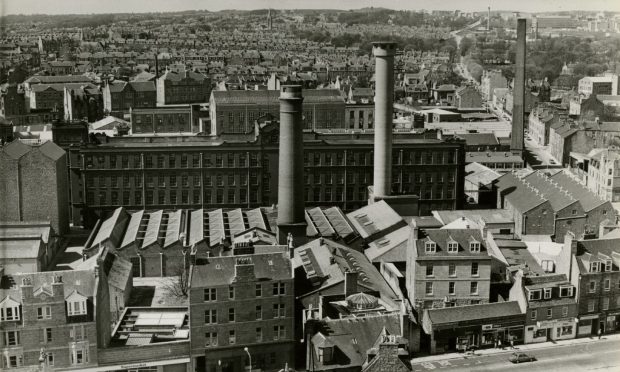

Now, two decades after Richards vacated the Broadford Works, the vast buildings remain derelict as plans to redevelop the site have fallen through.

The largest collection of A-listed buildings in Scotland, neglect and time haven’t been kind to these handsome, but sorry structures.

The Grey Mill, which still stands at the centre of the site, is the oldest iron-framed mill in Scotland.

And one of only four left in the world.

Where the Broadford Works once dominated manufacturing, they now dominate the Buildings at Risk register for Aberdeen.

Behind the perimeter walls there existed a hive of industry, a community and camaraderie.

In the morning the Broadford bell would ring, summoning workers to the mill. Answering the call, neighbouring streets would swarm with staff.

Long gone is the familiar humdrum, the whirrs and rattles of machinery. Instead silence fills the empty buildings.

You can imagine the busy footsteps on the smart granite setts that lined the streets between the mill buildings in its heyday.

Now trees and foliage grow between those setts, and only birds flit between the buildings.

The fragmented panes of the remaining windows glint in the autumn sunlight.

They almost give a glimmer of life to these hollow structures which bore witness to 200 years of life and work in Aberdeen.

Broadford Works song

An old song workers used to sing at Broadford Works was shared with the Press and Journal in 1987:

Some Bonnie mornin’ I’ll rin free,

Broadford bells winnae for me,

They’ll ring for ane and they’ll ring for twa’,

An’ they’ll ring for the bonnie lassies far awa’,

The pickin shop I saired mi time,

Darnin’ canvas neat an’ fine,

But little wages winnae dee.

Sae I’m awa’ tae bonnie Dundee.

It’s nae for the leavin’ o’ the bonnie mill,

Nor hiv the lassies din me ony ill,

It’s jist through Simpson an’ his ill will,

Thit I am leavin’ the Broadford Mill.

Conversation