Lived memories of the horrors of World War Two are fading with each passing year, but thankfully powerful public memorials to those who made the supreme sacrifice remain as a permanent tribute, and a focus on Armistice Day.

That includes the 55,573 young men who died in service with Bomber Command during the war.

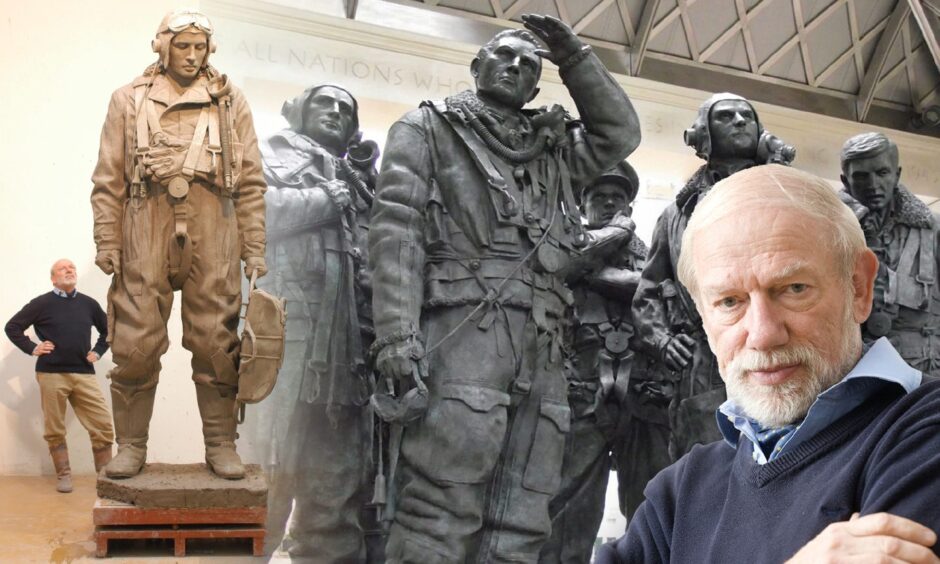

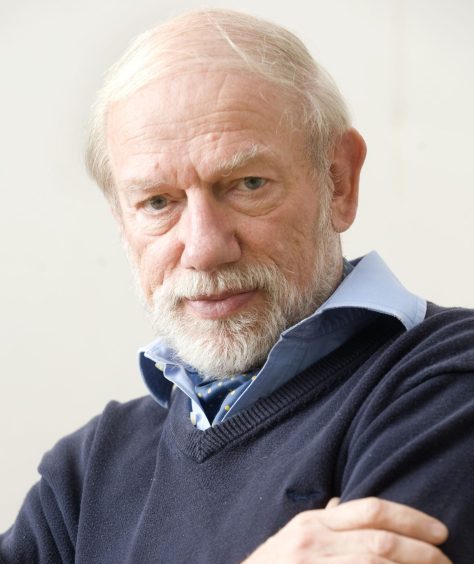

The imposing memorial to them in London’s Green Park, unveiled in 2012, was created by Inverness-born sculptor Philip Jackson.

The funding for it came from public donation in a drive led by businessmen and including musician Robin Gibb.

It’s not an easy brief, to create a full Lancaster bomber crew of seven in a group of 9ft high bronze statues.

Philip had mixed feelings about taking on the brief at first.

He said: “I was asked on a couple of occasions whether I’d like to do it and my first answer was yes, very much, because my father started his war in Bomber Command, but when I heard how quickly they wanted it, I turned it down.”

Philip’s father flew in Bomber Command, volunteering later for the Fleet Air Arm, flying off aircraft carriers.

He was shot down off the coast of west Africa while attacking the French battleship Richelieu.

A French flying boat picked him up, and he was imprisoned in Mali, inspiring in him a love for Africa, where Philip ended up spending much of his childhood.

Philip continued: “On the third time of asking I must have blinked because I found I’d got the commission, and they immediately said, can you very quickly do a sketch of what you’ve got in mind.

“But I hadn’t really got much in mind at that point.”

Philip found himself forced into dangerous territory.

“I spent a weekend wading through bookshops for books on Bomber Command, finding them few and far between.

Philip made a small sketch

“I did a small sketch, which I then sent up to RAF club in London, where they were having a meeting and talking over things like fundraising for it.

“One of the big fundraisers was the Daily Telegraph, and unbeknown to me, the Telegraph took a photo of my sketch and put it in their newspaper.”

At which point all hell broke loose from Bomber Command veterans.

Veterans furious

Philip said: “I had an avalanche of mail from veterans saying things like the parachute straps were too long, boots too short and so on.

“This had just been a sketch to show concept and position of figures, I hadn’t bothered at all with the accuracy of what the chaps were wearing, so we wrote to all these angry vets saying don’t worry about it, it’ll be very different when it gets large-scale.

“With military sculptures, most of those who look at it are more interested in the detail being correct, rather than the artistic merits of the thing.”

Philip set about drilling into the all-important detail.

“I told my clients I needed to have every bit of kit that the crew of a heavy bomber would have worn, and it can’t be reproduction, it must be the real thing.

Devil in the detail

“I needed to know who wore what, how it was worn and why, because I have to be more of an expert than these people who are going to make my life misery.”

Philip sourced what he needed from the RAF Museum at Hendon, and set to working on the first figure.

For such huge sculptures, a small-scale maquette is made first, and Philip focused on the crew’s navigator.

“I did the first figure, another maquette which I made sure wasn’t shown in the press, then I carried on with the first full 9ft figure.

“When it was ready to view, we invited to the studio the angry group of veterans who had been waiting for 60 years for recognition of what they did during the war.

“Bomber Command took the war to the enemy from almost the first day of the war to the last, and lost more than 55,500 men, so they were pretty angry and didn’t want some abstracted sculpture done by some hairy artist with no concept of what they’d been through.”

Things didn’t start well when the veterans arrived at Philip’s West Sussex studio.

“They were very unfriendly. We tried to soften them up with tea and buns but it made no difference at all.”

With butterflies and bated breath, Philip and his wife Jean eventually took the veterans to the studio and unveiled the figure.

Deathly silence

“There was this deathly silence as they looked at this figure of the navigator, which of course towered above them.

“Jean and I were at the back and you could almost literally see the hostility draining out of them.

“It was what they wanted, they wanted something as they remembered themselves 60 years earlier and they remembered themselves their comrades who were killed.”

Philip said he wanted the figures to be quietly heroic.

At one point during the war, the average expectancy of a Lancaster crew was just two weeks.

He said: “It’s one thing to do a brave act once, but to do it night after night and be shot at over enemy territory in the dark and cold took a particular type of bravery.”

Once the ice was broken Philip and the veterans became firm friends.

Friendships forged

“Every time a figure was finished, we’d invite them down and they would drink us out of wine and everything else.

“They became great friends, of course, sadly they’re all dead now because when they came down they were in their late 80s, early 90s.

“But it was important to have them down because if there was anything wrong with the sculpture they would have noticed it and they didn’t notice anything.”

Queen Elizabeth carried out the unveiling, with various members of the Royal family present.

Philip said: “There were about 7,000 people there and they all trooped past the memorial.

Mementos

“Most of them left mementos that they’d been holding onto for 60 years, and now they wanted to place these things at the feet of the people they remembered.

“It’s then that you realise the importance of these sorts of memorials even 60 years after the event, it’s a sort of national memory if you like, somewhere people can go to remember their comrades and that’s important.”

One area of the brief Philip felt unable to follow was the request to make the men look young. After all, the average age of a bomber crew member was just 22.

“I said, let me just have a look at the reference material.

“When I looked at the photos of people coming home from a raid, they didn’t look young at all.

“They knew what their chances of survival were after the first few missions.

“If you’d been sitting at the back of an aircraft on your own, cocking and uncocking a gun, because if you didn’t it would freeze up in minus 40, and you were doing that for nine hours, you’re not going to look young when you landed.”

More like this:

Meet the Bridge of Don veteran, 98, who saved his crew on a night raid over Germany

Conversation