When dress historian Jo Watson gets the bit between her teeth, she goes all out.

Not content with recreating in painstaking detail the serving woman Betty Burke’s disguise made for Bonnie Prince Charlie to wear to escape from the Hebrides to Skye after Culloden, Jo decided she must also recreate the shoes he wore.

And then wear them herself to walk part of the route he took across Benbecula to the fishing bothy where he hid overnight before slipping away in a boat with Flora MacDonald next day.

The key to recreating both the Betty Burke servant costume and the shoes was the book Lyon In Mourning, written by Robert, later Bishop, Forbes, who captured eyewitness accounts of the Jacobite flight from Culloden after the defeat of 1746.

He produced most of it in the five years following Culloden, a priceless and vivid insight into the turmoil and strife of the time.

It was from the Lyon in Mourning manuscripts, held at the National Library of Scotland, that Jo found all the clues she needed for the Betty Burke outfit, including a fragment of the very material used for the frock section.

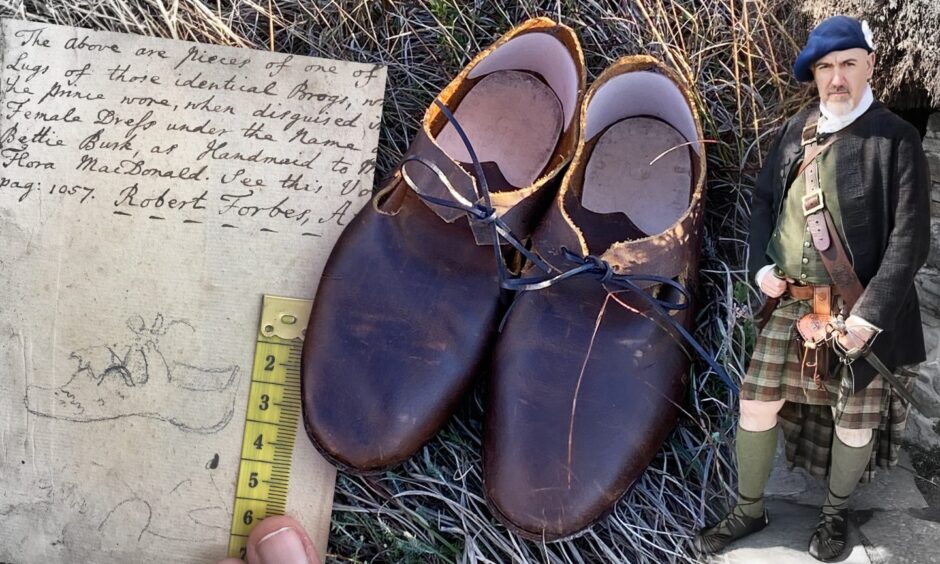

So what did the Prince wear on his size 10s, Jo wondered. “We know he was a foot size 10 from the length of his thigh, revealed by his breeches.”

Robert Forbes provided the answer in his book.

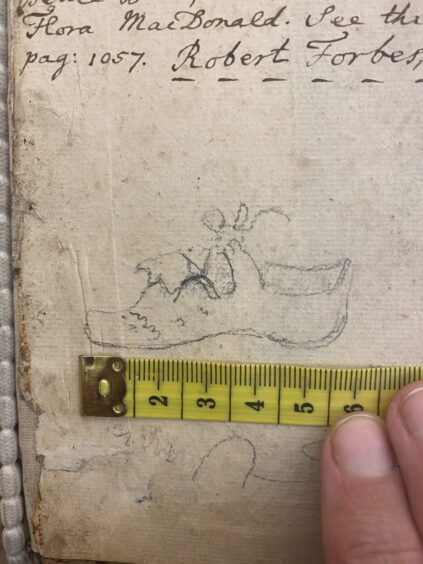

Jo said: “I read about them in Lyon in Mourning and saw the sketches of one of them too.

“The original pair of shoes does exist, hidden away in a private collection and unavailable for the public to view.

“Then when I saw Professor Hugh Cheape’s photo of them from around 1980 I knew it had to be done.”

Next problem— Jo is a seamstress, shoe-making is not her thing.

She got in touch with her old pal, The Targe Man, John Stewart, historic leatherwork supremo.

John lives in Larbert, and was originally a construction worker.

Discovering his leather-working talent came from joining the Jacobite re-enactment society, Alba Re-enactment, some 25 years ago.

Craftsman John Stewart’s targe-making journey

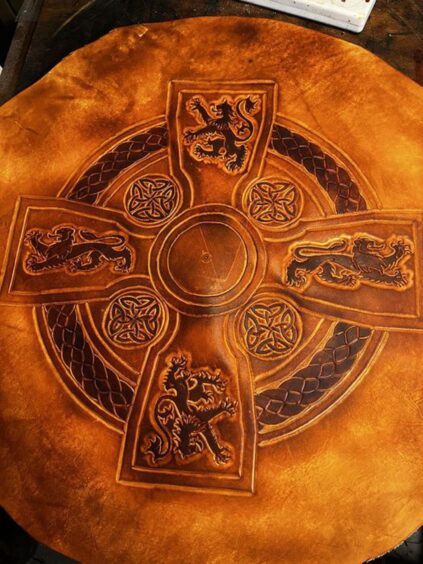

When he saw it was possible to make your own targe, he decided that making one for himself, along with the leather accessories also required, would be a way around the considerable expense of buying them.

He said: “I made my first targe out of Grandpa’s old chair when I was in my late twenties.

John read up extensively on how to do leather work and his repertoire expanded to include belts, sporrans and pouches as well as targes.

He soon became very popular with other re-enacters.

“When others saw them, they asked if I could make them a targe, so they paid for the materials and I made them. I helped a lot of folk get their kit together.”

Eventually John was forced to give up Clan Alba due to the arthritis in his knees.

“We parted ways but I carried on targe making, with orders coming in from all over the world,” he said. “I don’t do it commercially as I’m still working. I work in hospital maintenance at Forth Valley hospital.”

Surprising request to recreate Bonnie Prince Charlie’s shoes

Then Jo got in touch with her surprising request.

“She said could you make me the Bonnie Prince Charlie shoes? I’d never made a shoe in my life, but I said I’d give it a try.”

John had to work from the Lyon in Mourning sketch and the photo of the original.

Very little to go on

“That’s all I had to go by,” John said. “No sizes, measurements or nothing. I couldn’t even see the heels.

“The leather seemed to be folded over the feet, with holes to let the water through.”

John turned to videos and books for tuition, but they were for modern shoes and of limited use.

Nothing daunted, he made his first ever pair of shoes, 18th century style, for his wife, Susan.

They were quite a success, so he ordered cowhide and ploughed on with the Bonnie Prince Charlie shoes.

They would be on the small side for the Prince, as John could only find a size 8 last.

He formed a scalloped tongue and two flaps that join in the middle normally for a buckle but in this case for leather laces or ribbons.

“Jo told me Charles had two pairs, one pair made in three days, and one which was given to him. One of the pairs was all cut up as souvenirs.

“It took me a week to make them, and I had to guess at how the heels were made. In the end I made them of stacked leather.”

The ‘best guess’ shoes will be made public, with a select few able to try them on, Jo says.

Not content with merely admiring John’s work, Jo decided she must walk a mile, or a little way at least, in the Prince’s shoes, along the very path that he would have walked on his way to escape, at Reuval in Benbecula.

“They were enormous, but incredibly comfortable,” she said. “My experience of 18th century shoes from living history is that they are incredibly comfortable, and usually being made entirely of leather, more breathable than modern shoes.”

Jo says she has learned a lot from recreating 18th century wear for the project.

“It tells us so much about the preciousness of materials and about the techniques made to make the clothes.

“Eighteenth century clothes were made to fit the wearer, and people generally didn’t own many clothes at any one time.

“The quality of material and styles has always denoted social class, and this project was no different.

“It was quite clearly written in Lyon in Mourning that the

Betty Burke clothes were made to suit a servant, so weren’t as fine as something contemporaries on the islands like Lady Clanranald and Flora MacDonald would have worn.”

She was thrilled recently to find out that her reconstruction of the Betty Burke outfit is now being shown to postgraduate students at Simon Fraser University in Canada to demonstrate how excellent a disguise the clothing was.

Jo said: “It has helped correct some of the false narratives about the outfit, including the satirical sketch done in London at the same time which was designed to make him appear effeminate and emasculate him.”

The project has also given Jo pause for thought about the ‘fast fashion’ of today.

“What a dreadful use of resources it is.

“I would truly love to get back to a society where more folks make their own clothes, look after them and think more about where the materials came from and how far away they came from too.”

Jo sewed the Betty Burke outfit at Nunton House in Benbecula, where it would originally have been made, in June this year.

Having now made a recreation of Flora MacDonald’s wedding attire as well as the Bonnie Prince Charlie Betty Burke disguise, she’s decided to take recreating historical dress to an incredible next step of authenticity.

She said: “I’m intending to grow flax next year and see if I can make a set of stays to make an eighteenth century style corset, and I will chart how much time and effort goes into that one garment.

“For me, reconstructing, or recreating, historical dress brings the history alive, because clothes are such an important expression of our inner selves to the outside world.

“What we chose to layer ourselves with says so much about us as individuals.”

Jo’s project is funded by Creative Scotland through Highlife Highland’s Spirit 360 project.

More like this:

Jacobite heroine Flora MacDonald’s wedding attire painstakingly recreated

Conversation