Bennachie – often regarded as Britain’s best-loved hill – has an enduring, mystical appeal holding many secrets… like a hidden waterfall within her ancient woodlands.

Beloved locally and steeped in folklore, even the late Lord Aberdeen was quoted as saying: “To Hell with your Alps, Rockies and Himalaya, Bennachie is the hill for me.”

In 1945, the Mither Tap summit was described in the Press and Journal as having a “magnetic attraction” akin to that of a holy place.

Referring to “the sacred mountain of Aberdeenshire”, the writer went on: “All people born within the shadow of the Mountain of Light must bow down and worship at the Mither Tap.”

Certainly, a New Year’s Day trip to Bennachie to blow away the cobwebs is an annual pilgrimage for many in the Garioch.

Although for many more, it’s a frequent ritual.

A hill with a history stretching back millions of years has many secrets and stories to tell.

From historic graffiti at the Mither Tap, to Pictish stones telling stories about the Devil claiming Aberdeenshire maidens, there’s almost no end to the tales, both tall and small, of Bennachie.

Here are seven of our favourites…

1. Bennachie plane crash claimed first allied victims of WW2

Just four hours after the outbreak of the Second World War, its first victims were not claimed on the battlefields of Europe, but on the slopes of Bennachie.

At 11.15am on September 3 1939, Prime Minster Neville Chamberlain broke the grave news that Britain had declared war on Germany.

And at 3pm, Pilot Officer Ellard Cummings and his gunner Leading Aircraftman Ronald Stewart became the first official casualties of the war.

They died when their Westland Wallace biplane hit Bennachie’s Bruntwood Tap summit in poor visibility.

The pair were flying from the Air Observers School at RAF Wigton to RAF Evanton in Easter Ross.

But the final leg of the journey from Dyce – and their young lives – ended when the plane ploughed into the wooded slopes of Bennachie.

Pilot Officer Cummings, from Ontario in Canada, was just 23 years old, while Leading Aircraftman Stewart was 24 and about to marry his fiancé.

Charlotte Marr, who lived at nearby Tilliefour Kennels for decades, was just 17 when the wartime tragedy happened.

Recalling the incident in 1975, she explained how she climbed the hill to view the wreckage of the two-seater aircraft.

She said: “We heard the plane go over, through the fog, then later heard a loud bang, but it wasn’t until the following day that two forestry workers found the wreckage and the two men sitting dead.”

PO Cummings was buried at the Grove Cemetery in Aberdeen, while Leading Aircraftman Stewart was buried in his hometown, Paisley.

But the decaying engine and debris lay untouched on Bennachie until the 1960s, when incredibly a firm recovered it with the intention of selling it as scrap.

The nine-cylinder engine was left undisturbed in the forestry plantations before disappearing.

Charlotte was visited at her cottage by RAF officers in 1975 on the hunt for the wreckage.

She explained: “They said they were interested in locating any of the piston engines, which they wanted for their museum, but they were unable to locate any of the plane wreckage.”

Three years later it turned up at an auction at Sauchen in 1975 where it was described in the Press and Journal as “a grim memento of a north-east air crash”.

It was in May 1975 when it appeared at the wood contractors in Tillyfourie, owned by Robert Burr and his sons James and Robert Jnr, who were holding the sale.

The auctioneer advised the pair to withdraw the lot and contact the RAF, suggesting it was likely still MOD property.

The RAF reclaimed the engine with a view to putting it on display, but its whereabouts remain unknown.

A granite memorial was constructed by the Bailies of Bennachie in 2012 and some debris still lies scattered on the hillside, left untouched as a mark of respect.

2. Bennachie scene of fatal jet crash in 1952

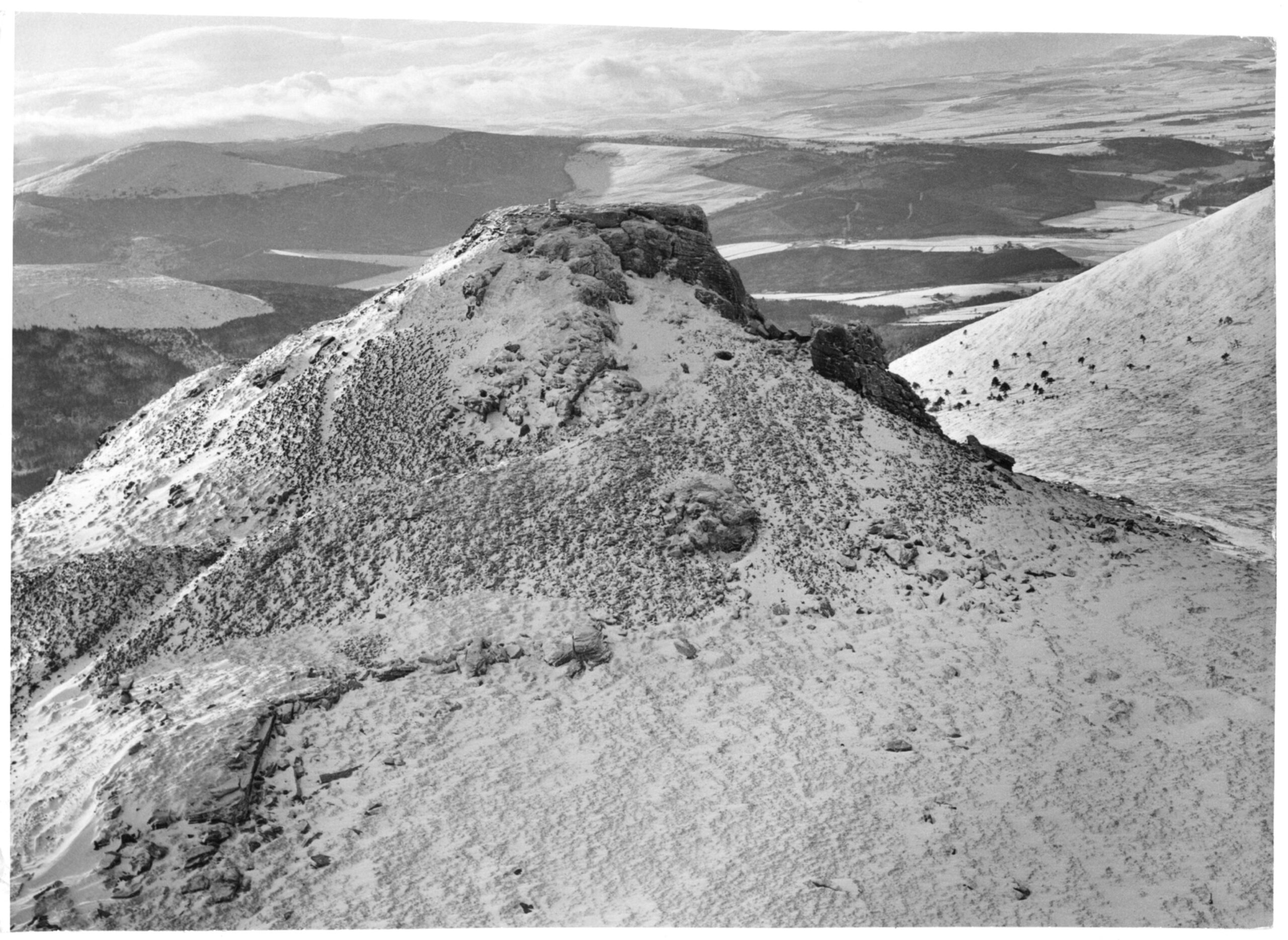

Bennachie was the scene of another air disaster in 1952 when a jet fighter crashed west of Oxen Craig on February 12 1952.

The Gloster Meteor single-seat turbo-jet fighter was being flown by RAF Pilot Officer John Brian Lightfoot when it smashed into the hillside.

The 22-year-old from Northallerton was killed instantly.

He left RAF Leuchars just before 10am to take part in a low-flying exercise.

But the weather in the Garioch was poor, and at around 11am the plane disappeared in driving snow with a bang.

There were many accounts from locals, including that of Charlotte Marr from Tilliefour who had now witnessed her second air crash on Bennachie.

She saw a column of smoke rising from the slopes where the jet was last seen.

The barman at Premnay Hotel at the Back of Bennachie saw the plane fly overhead “in a blinding snowstorm” and exclaimed: “It’s flying right into the hill.”

Mr Williamson of Glenton, Monymusk, heard the plane flying low before a dull crash followed.

He saw the plane drop something which exploded on the ground before it crashed.

The Monymusk resident reported the incident to a Forestry Commission official who then telephoned the police in Inverurie.

Mountain Rescue from RAF Edzell began to ascend Bennachie above the River Don at Tilliefour.

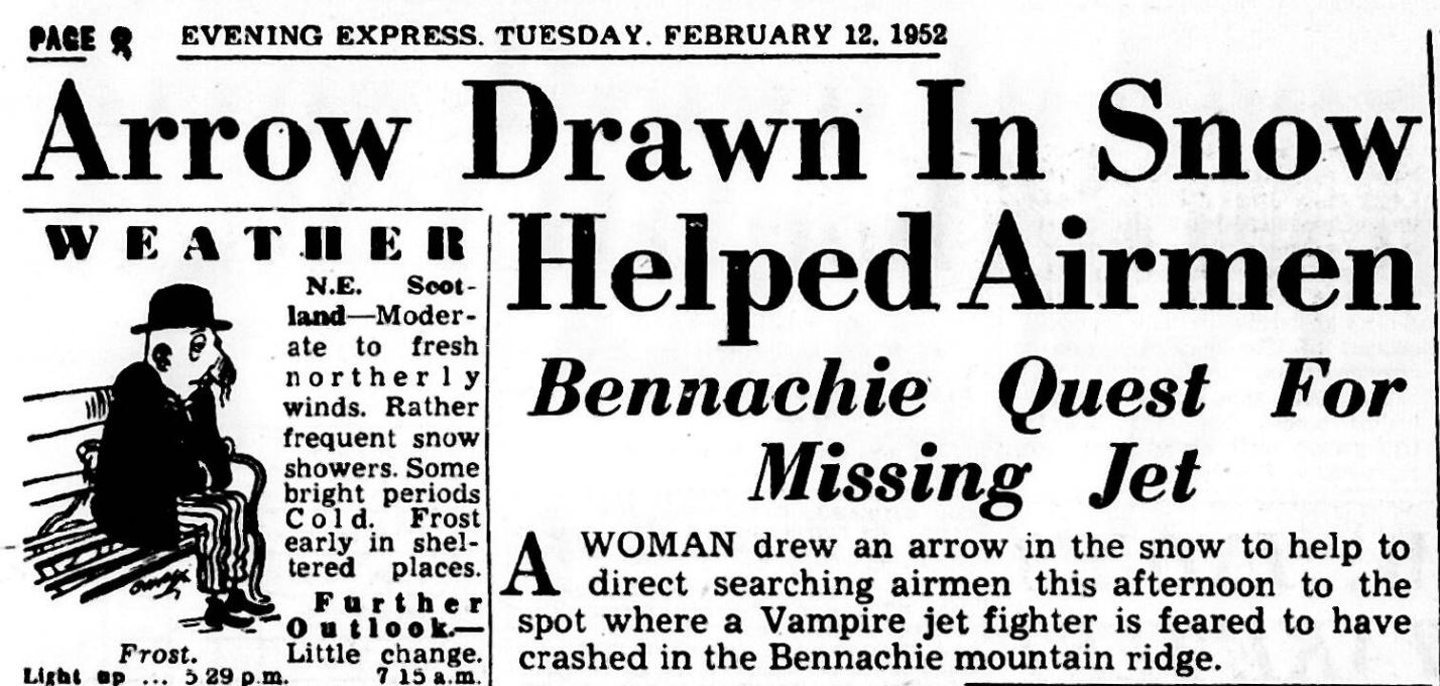

To aid them in their efforts during the adverse weather, Charlotte drew an arrow in the snow directing the searching airmen to the moorland slopes.

Ultimately it was the help of an Evening Express reporter that led the search party to the aircraft site.

A story carried in the paper on the day of the crash read: “A reporter, who was in a radio car, which was receiving from the Aberdeen office of the Evening Express latest information flashes, was able to lead the RAF Mountain Rescue team to the area where the crash had been reported.”

The plane was eventually found four hours later at Watchcraig Seat near the Mither Tap on Bennachie.

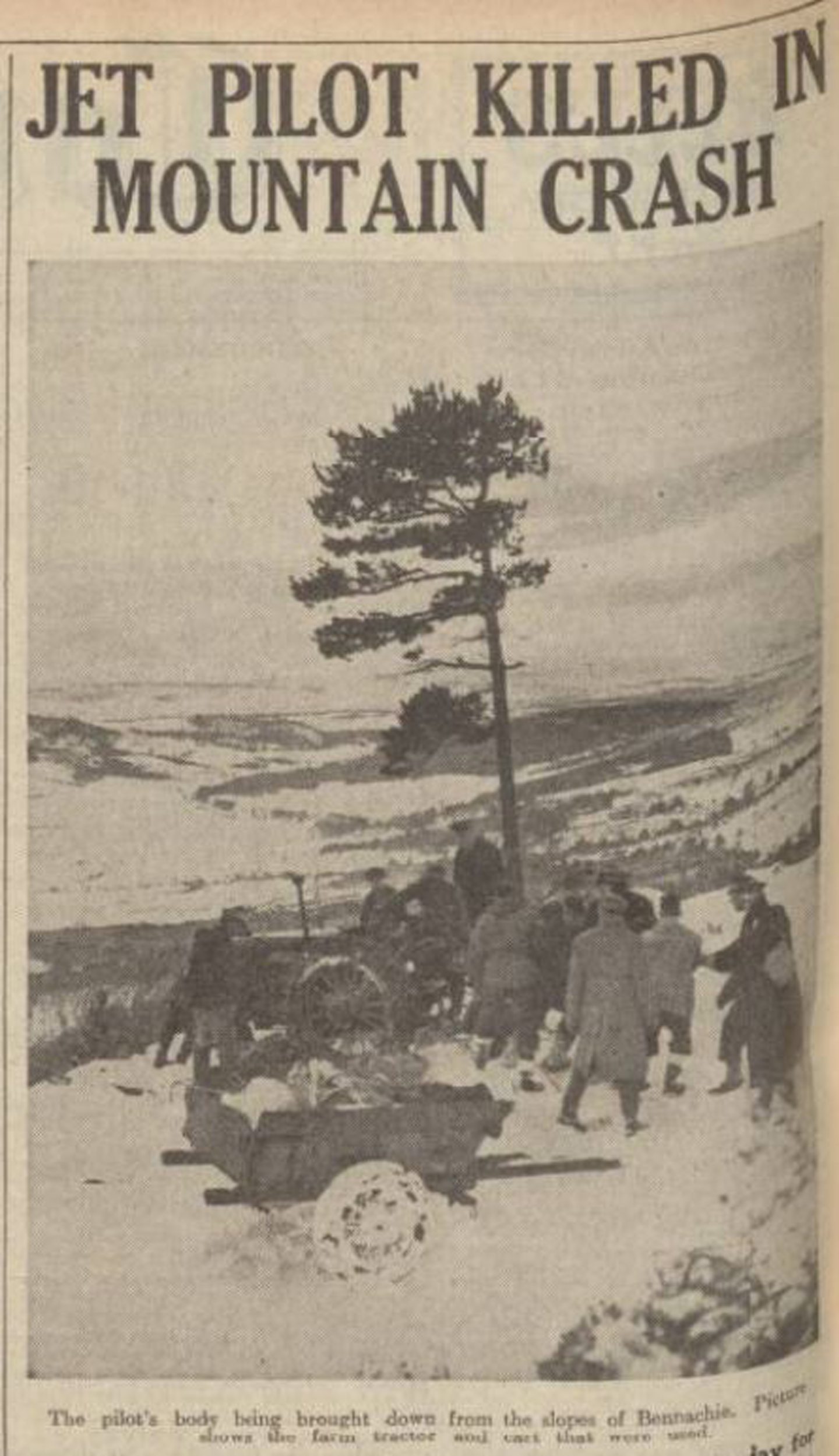

PO Lightfoot’s body was initially carried down the hillside on an improvised sledge made out of the metal part of the fuselage.

It was then brought down by a tractor and trailer from the nearest farm at Mill of Tillyfour.

He was buried with full military honours in a Commonwealth War Graves Commission grave at Leuchars Cemetery.

The wreckage was buried at the crash site, but one of its cannons hangs from the ceiling of the Bennachie Visitor Centre.

3. Clues to life on Mars could lie at foot of Bennachie

It’s a long way from the red planet, but a rare mineral discovered on Bennachie may hold the secret to life on Mars.

Only found in Aberdeenshire, the blood-red mineral Macaulayite was discovered in the 1970s by the late Aberdeen scientist Dr Jeff Wilson.

Formed in the presence of water, if a similar substance occurs on Mars it could provide proof the planet can sustain life.

The fine-grained substance was found by soil scientist Dr Wilson in the disused Pittodrie quarry at the foot of Bennachie.

The name Wilsonite had already been used, so Dr Wilson named it Macaulayite after The Macaulay Institute where he worked.

It was thought it could be the same mineral, a hybrid of elements similar to iron oxide and clay, which gives Mars its red colour.

Dubbed one of the rarest mineralson Earth, in 2009 a sample was sent to scientists at American space agency NASA for testing.

It’s not yet known if the testing has concluded.

4. The hardy, rent-free colonists who lived on Bennachie

The ruinous footprint of a small croft is all that remains of the once-thriving colony that once lived on Bennachie.

On a bitterly cold winter’s day with biting wind and the ground frozen solid, it’s hard to imagine anyone called the hill their home.

In 1801, the first colonist build a but and ben on the south-east slope of Mither Tap.

At its height there were around 75 people living in crofts there.

Entirely self-sufficient, the colonists carved out a tough life for themselves living off the sparse land.

They cultivated small vegetable gardens, raised animals and worked in the hill’s quarries.

Many of the men were labourers who walked miles to work each day.

It was not an easy life, yet many people were resentful the community lived rent-free on Bennachie.

In 1859, nine neighbouring lairds decided to take ownership of Bennachie and therefore the colony.

They divided up the hill and removed any right the settlers had to the free forest forcing the settlers to pay rent or leave.

One by one the families were forced out, but the Essons clung on to their Bennachie home until George Esson, the last colonist, died in 1939.

5. The Thieves Marks carved on Mither Tap

We tend to think of graffiti and vandalism as modern phenomena, but initials left by Victorian ramblers remain on Bennachie more than 200 years on.

Over the years, a number of people have made their mark on the hill, inscribing names and words into bedrock at the top.

At the summit of Bennachie’s tallest peak, Mither Tap, dozens of names and dates are carved into the granite.

The most significant initials were perhaps those of the local lairds who ousted the colonists and claimed Bennachie for themselves in 1859.

Straight lines were drawn on a map to divide the hill among the nine neighbouring landlords.

A number of boundary stones marking the division of the community of Bennachie are scattered around the hills outlining each laird’s stake in Bennachie.

But a flat stone at the top of Mither Tap carved with the letters B, P and LE and dated 1858 is known as the Thieves Mark.

The initials stood for Col Leslie of Balquhain, Col Erskine of Pittodrie and Sir James Dalrymple-Elphinstone of Logie Elphinstone – the three closest estates whose lands met at the summit.

6. The secret waterfall and fog house

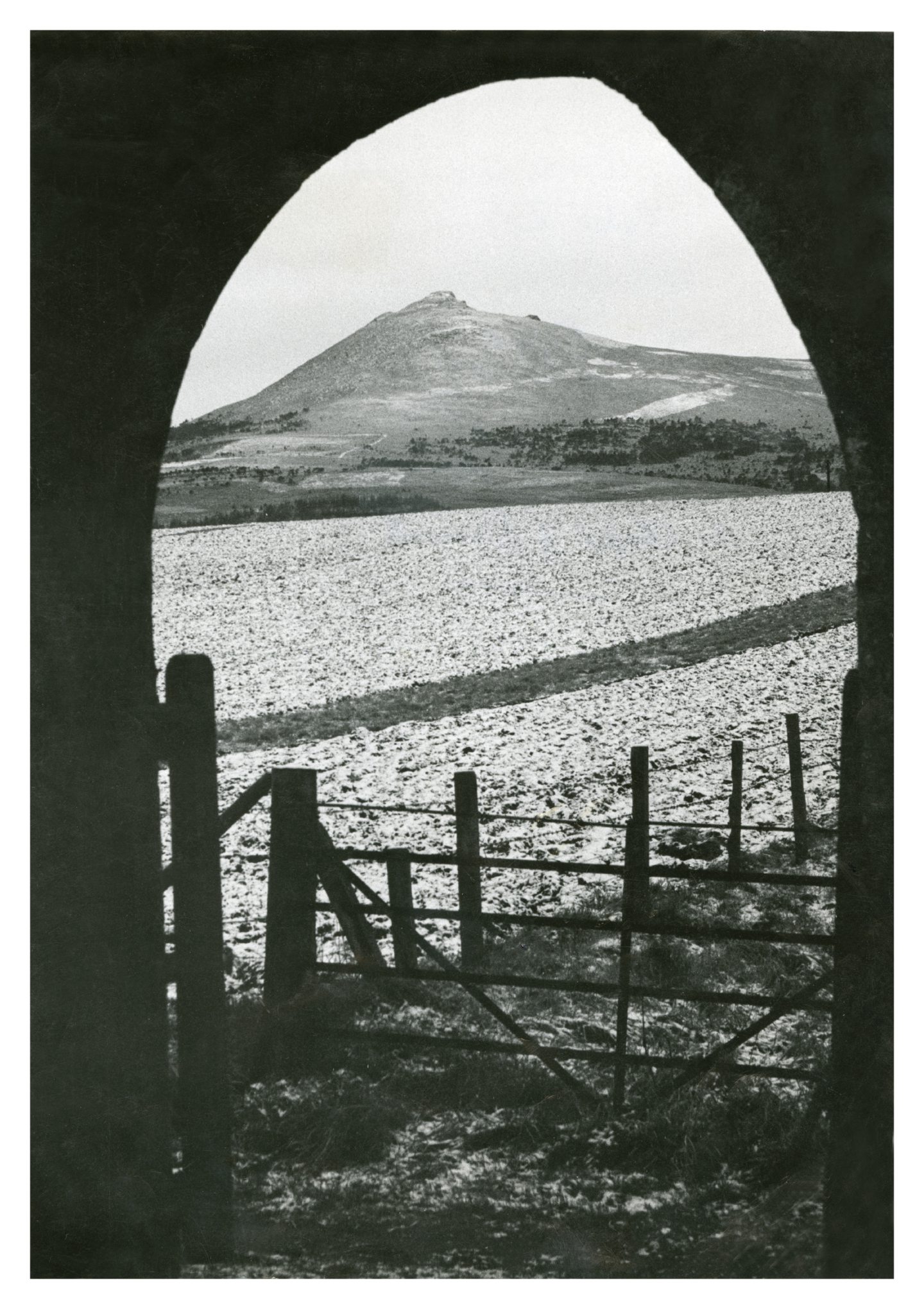

One of Bennachie’s best-kept secrets is the fog house overlooking the linn, or waterfall, on the lower slopes of the hill.

The curious, roofless ruin is believed to be a Victorian folly likely once part of Pittodrie estate, as it is frequently referred to as ‘the Linn of Pittodrie’ in historic newspapers.

The small structure with stone walls stands on the banks of the Rushmill Burn, its arched windows providing views over the waterfall and the surrounding non-indigenous rhododendron.

With no defined path or instructions to get there, the fog house has an almost mystical quality, like an ancient woodland temple.

Located in dense woods off the old turnpike road, many walkers have tried and failed to find the famous fog house.

Its history is even more mysterious – nobody quite knows why it is there, who built it, or when.

But it’s most likely it was some kind of summerhouse on the former estate policies of nearby Pittodrie House.

Reference is made to the fog house folly in the Banff Journal in 1864: “We have heard of a party of excursionists who, two years ago, went to the waterfall at Pittodrie where there was a pretty summerhouse.

“They might have enjoyed themselves in the place, and no-one would have interfered with them; but they broke the windows and took the door off its hinges, and, throwing the furniture into the burn below, left it for a ruin.”

The fog house and linn seemed to have been a hidden gem shown off to a select number of Victorian daytrippers.

The Aberdeen Free Press in September 1891 ran a huge feature entitled ‘a day out on Bennachie’.

A highlight for the writer was a detour “to inspect the Linn of Bennachie – a ‘wee’ waterfall beautifully situated in the woods of Pittodrie”.

In 1896, Inverurie Lawn Tennis Club’s annual picnic to Bennachie – by horse and carriage – took in the Linn of Pittodrie, “the beauties of which were greatly enjoyed”.

While a walking party from Oyne in August 1902 “with the kind permission of Mr Booth, lessee of Pittodrie House, proceeded to view the Linn of Pittodrie, a piece of scenery which was greatly admired”.

Enjoyed by excursionists for decades, Storm Arwen has made access difficult, almost leaving the secret summerhouse to be reclaimed by Bennachie.

7. The Pictish Maiden Stone

Bennachie’s Pictish history is well documented – Mither Tap was an ancient hill fort conveying the power of the tribe far and wide.

The tribe of painted people were famous for their curious carvings etched into stones, which are scattered around Aberdeenshire.

One of the best known and best preserved is the Maiden Stone, the story of which has been retold to generations of schoolchildren.

The 3-metre-long stone of pink granite stands tall on the foothills of Bennachie near the farm of Drumdurno.

It dates to around 700AD and bears vivid symbols of a cross, some kind of water beast, a comb and mirror, and a cavalry-like scene.

The mysterious imagery has lent itself to folklore and storytelling.

The most well-told tale gives the stone its nickname – the Maiden Stone.

Legend has it that the daughter of the Laird of Balquhain was baking on her wedding day when she bet a stranger that she would finish her bannocks before he finished building a road to Bennachie.

But this stranger was the Devil and he of course won the bet to claim her as his wife.

Realising her fate with horror, the young maiden turned on her heel and fled, but was turned into stone when he reached out and grabbed her.

The notch in the stone is said to be where the Devil clutched her shoulder.

If you like this, you might enjoy:

Conversation