Early in World War One, two women, one with roots in Strathglass and Nairn, set up an independent field dressing station a mere 100 yards from the front line at Ypres in Belgium.

Amid scenes of unimaginable horror, they acted as first responders to thousands of soldiers for almost the duration of the war, until they were themselves gassed out in 1918.

The Germans deliberately targeted and shelled their little cellar-hospital on several occasions.

Undaunted, the women simply moved to whatever wreck of a building they could find nearby and continued their work.

They were the only two women operating so close to the front line in any theatre of that terrible, global war, and received many medals for bravery at the time.

And one of them was only a teenager.

Famous, feted and forgotten

Although they were the most famous and feted women of that war, they’re all but forgotten now.

Mairi Lambert Gooden-Chisholm of Chisholm was the younger of the two, 18 years old at the outbreak of war.

Her friend Elsie Knocker, later Baroness de T’Serclaes, was 30, a qualified midwife, a divorcee with a young son.

Shared love of motorbiking

The two had met before the war over their shared love of competitive motorbiking, at which both excelled, bringing to the sport their own madcap recklessness.

Mairi was the daughter of Captain Roderick Gooden-Chisholm of the 3rd Battalion Seaforth Highlanders (Ross-shire Buffs, Duke of Albany’s).

He was chief of the Clan Chisholm, whose seat at that time was Erchless Castle, in Strathglass close to the River Beauly.

On Mairi’s mother’s side, her grandfather was Colonel William Fraser of Redheugh, Culbokie, living in Nairn.

Roderick met his wife, Margaret ‘Nonie’ Fraser when he was stationed at Fort George, near Nairn, and the two were married in 1893.

Moved south

The following year, he resigned his commission, and the couple moved south to Datchet, Windsor.

His father was part of the rich Scottish elite in London, dedicated to all things Scottish, supporting the Highland Society, the Scottish Hospital and the Royal Caledonian Schools.

Mairi Chisholm born to quiet privilege

Mairi, born in 1896, had a privileged but unostentatious life.

The family’s multi-million pound fortune was tightly controlled, allowing them to live well, but not extravagantly.

The family moved to Bournemouth, Dorset in 1900.

Mairi and her older brother Uailean were close, educated together at home by a governess in their early years.

No emotions allowed

It was very much a ‘stiff upper lip’ household, and perhaps the emotional privations protected Mairi from the horrors she would find herself confronting on the front line some 14 years later.

Author of ‘Elsie and Mairi Go To War’, Diana Atkinson says she and her brother “were taught not to squeal if hurt and never to display emotion, and in all the time I lived at home my mother never kissed me.”

She and Uailean were once found digging a hole in an aunt’s garden and when asked what they were doing replied: “We are burying our parents.”

Never a dull moment

There was never a dull moment in the life of the well-connected Gooden-Chisholms.

As one small example, one day in 1910 King Edward VII dropped in with his mistress Mrs Keppel to play cards with Mairi’s father.

But high society ways and being a lady didn’t interest Mairi.

She was a complete tomboy, borrowing Uailean’s clothes and mucking about with machinery, covered in grease and stripping down engines.

Becomes her brother’s mechanic

She became Uailean’s mechanic when he competed in local motorbiking events.

Much to her mother’s horror, others spotted Mairi’s potential, calling her a born mechanic and suggesting she should have her own motorbike— and in 1913, aged 17, she did, an open-frame Douglas dropped-handlebar racing motorbike (costing the equivalent of £7,700 in 2024).

That summer she was to be found haring around the roads of Dorset and Nairn wearing Uailean’s overalls and a bobble hat.

That year, she also had one of the most important encounters of her life.

Two motorcycle enthusiasts strike up friendship, before war breaks out

She met Elsie Knocker, another motorbike enthusiast who had already made quite a name for herself, and the two struck up a firm friendship.

But that idyllic time couldn’t last.

War was declared on August 4, 1914 and Mairi and Elsie shot straight to London to join the Women’s Emergency Corps as dispatch riders.

Diana Atkinson writes: “One day Mairi was spotted by Dr Hector Munro [of Aberdeen], a socialist, vegetarian, suffragette and nudist, who was impressed by the way she rode crouched over her dropped-handlebar racing motorbike.

“He tracked her down and asked her to join his Flying Ambulance Corps to help wounded soldiers.

“She agreed immediately and recommended Elsie.”

Off to war, 1914

By September 25, and amid much tut-tutting at Victoria Station as they were the only women in trousers, they had left for Belgium, which was under sustained attack, having been invaded by Germany on August 4.

Their job was to pick up wounded soldiers, many of them German, mid-way from the front and convey them to the field hospital further back.

This introduction to the horrors of war was a mere prelude to what they would experience later.

Mairi wrote in her diary: “No one can understand… unless one has seen the rows of dead men laid out. One sees men with their jaws blown off, arms and legs mutilated.”

Under fire themselves

They were often under fire themselves, from snipers or shells.

But it quickly became clear to Mairi and Elsie that they could save more lives by treating men directly from the front line, so they left the corps and set up their own dressing station in an empty cellar in Pervyse, north Of Ypres and just 100 yards from the trenches.

Here they would spend the next three and a half years tending to the wounded and dying.

As well as doing what they could medically, the women made soup and hot chocolate for the soldiers, reasoning that a little TLC like they would have had at home would help them recover faster. If they were to recover at all.

They used their own funds to support their endeavour and when those ran out they went back to England and raised more.

Elsie arranged for them to be officially seconded to the Belgian garrison stationed in what remained of the town, and they came to the attention of the high and mighty.

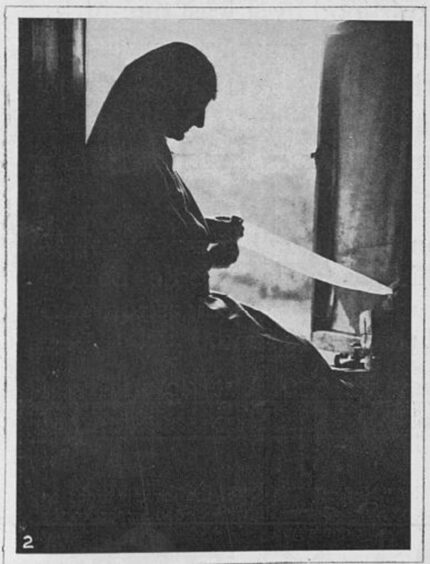

Bravery recognised early

In January 1915, only weeks after they started their work, they were both decorated by King Albert I of Belgium with the Order of Léopold II, Knights Cross (with palm)[5] for their courageous work on the front lines.

They were also awarded the British Military Medal and both made Officers of the Most Venerable Order of St. John of Jerusalem.

Mairi was also decorated with the Queen Elisabeth Medal of Belgium and the British campaign medals, including the 1914 Star.

Despite the unimaginable hardships, horror and privations experienced by the two women, romance did blossom for them in the wasted war lands.

Romance blossomed for both

Elsie met and married handsome Belgian soldier Baron de T’Serclaes.

Mairi became engaged to Jack Petrie, a Royal Naval Air pilot, but he died a year later during flying practice. She had another short-lived engagement to William Hall, a second lieutenant in the Royal Air Force.

Dodging bullets, shells, illness and privations of all sorts, the women pursued their work with extraordinary dedication.

Mairi told the Dundee Courier in 1916: “To dress, that means to brush one’s hair, to put on one’s boots. Of privacy there is none for others had perforce to share the cellar, for it was the only place in Pervyse which provides even a measure of safety from the shells which are constantly dropping into it.”

The Madonnas of Pervyse

The Courier referred to the women as The Two. Others referred to them as The Madonnas of Pervyse.

The Courier report went on: “They had been deliberately shelled while trying to save the enemy’s wounded; they had stuck to their ambulance which German, Belgium and French soldiers had surged around them in desperate hand-to-hand conflict… they are the only women allowed in the firing line.”

At one point water was so short that they slept in their day clothes for weeks on end, with Mairi having to be cut out of hers eventually.

They witnessed the most gory and grisly effects of war, men with their brains hanging out, with limbs shot off and half their guts blown away, and yet they never wavered from their self-imposed task.

Undaunted by the challenges

When things went wrong, as frequently they did, they simply picked themselves up and started all over again.

In 1918, a massive bombing raid and gas attack put an end to their work in Pervyse.

Mairi recovered enough to return to the front, but was forced to leave her post just months from the end of the war.

The poison gas had given her a weak heart, and she had contracted septicaemia amid the squalor, but she survived.

She and Elsie saw out the rest of the war as members of the brand-new Women’s Royal Air Force.

After the war

After the war, Mairi tried to continue with her fast-paced life, but on doctors’ advice returned to Nairn, where she became a successful poultry breeder with her childhood friend May Davidson on the Davidson family estate.

In the 1930s they took their business to Jersey.

Eventually, she moved to Cnoc an Fhurain in Barcaldine, Argyll where she, May and two others ran a poultry farm for decades.

In the 70s, she established the Clan Chisholm Society.

Despite all the bodily and emotional assaults she experienced in World War One, Mairi lived to 85, dying in 1981 of lung cancer in Perth hospital.

Elsie participated in World War Two, before a quieter life breeding Chihuahuas

Elsie participated in World War Two joining the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) as an Aircraftwoman 2nd class, becoming an officer in February 1940. Working with RAF Fighter Command, she rose to the rank of Squadron Officer in March 1942 and was twice Mentioned in Dispatches.

Tragically she lost her only son, Wing Commander Kenneth Knocker when he was shot down in 1942.

She turned to breeding chihuahuas and lived in Surrey until her death in 1978, aged 93.

You might enjoy:

William Carnie: The Kintore farmer’s son killed in one of WW1’s most daring tank missions

On This Day: How Aberdonians celebrated the first Armistice in 1918