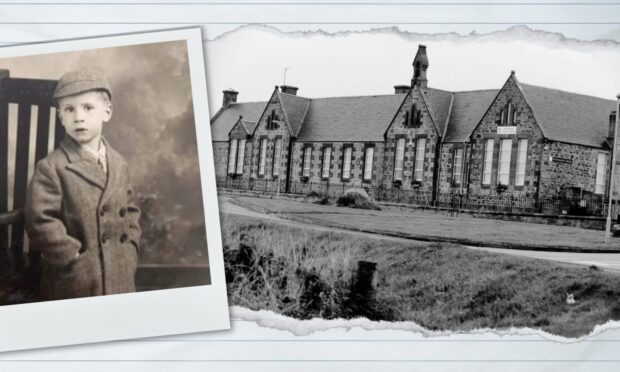

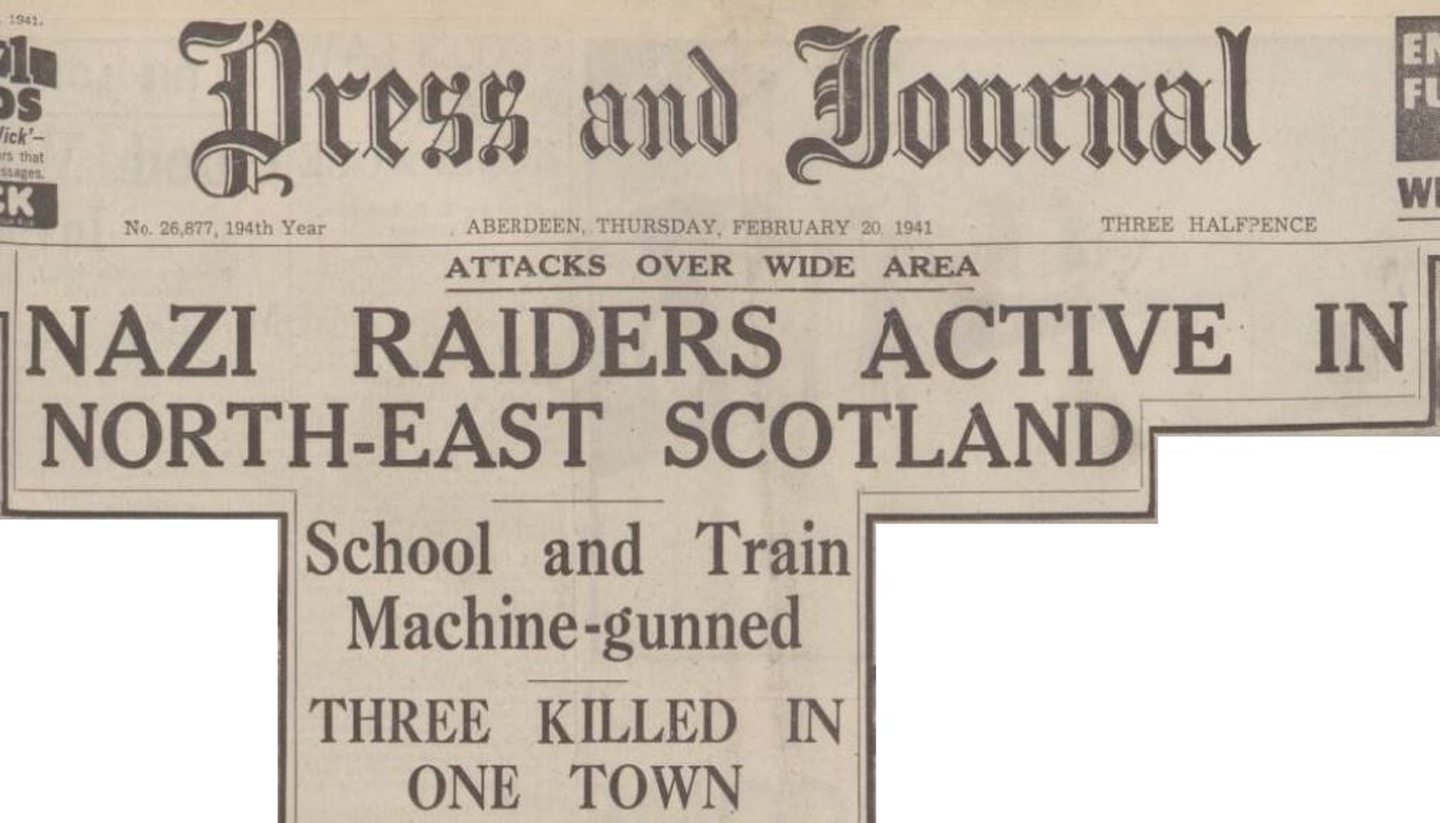

What started as a quiet day in the classroom at Portknockie School in 1941 ended in pupils diving under desks to escape strafing bullets from Nazi guns.

The scholars probably never thought their diligent air-raid rehearsals would become a reality in the sleepy seaside village.

Many children were evacuated from the Central Belt up to the coastal communities in the north-east of Scotland.

It was believed they would be much safer there away from the heavy industries and dockyards around Edinburgh and Glasgow.

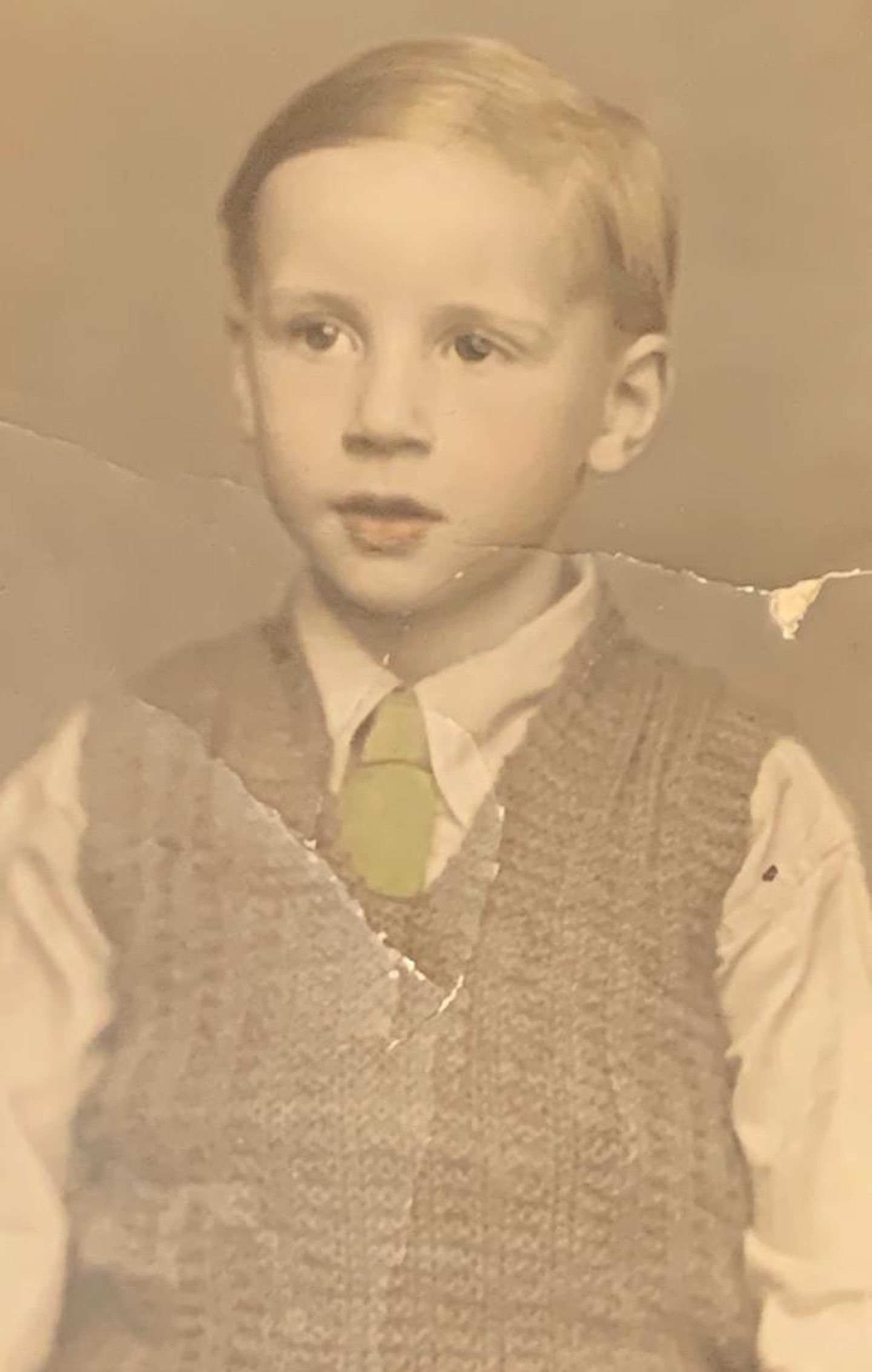

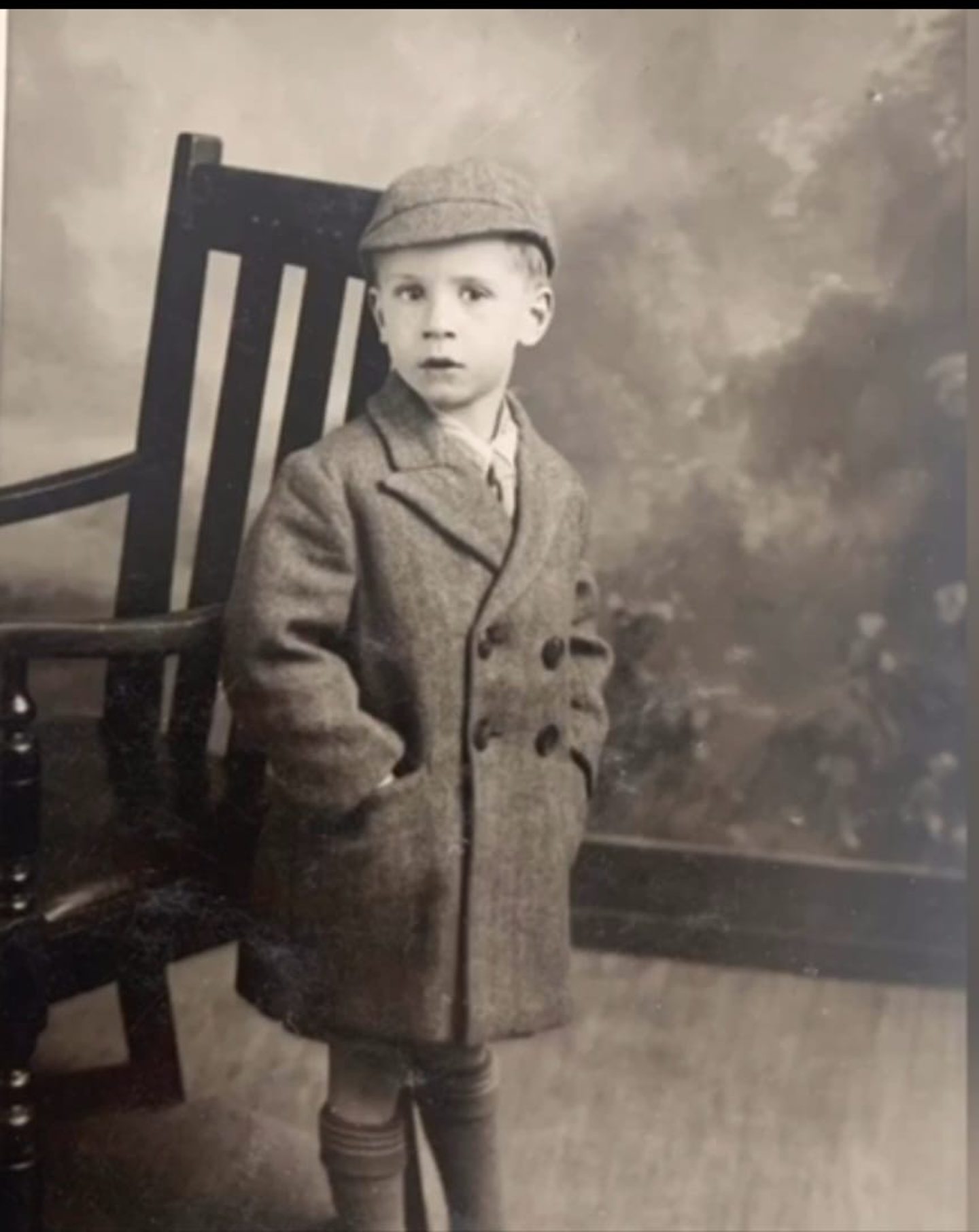

Among them was schoolboy Bert Ness, who had been evacuated from Leith in Edinburgh and found himself 200 miles away in the sanctuary of peaceful Portknockie.

Or so his mother thought.

But the north-east was not a haven from the horrors of war, far from it.

Portknockie was easy hit for Germans in ‘Hellfire Corner’

Famously, Aberdeen became known as Siren City due to the prolonged and terrifying night raids which saw hundreds of civilians killed.

And the sleepy, close-knit coastal communities weren’t immune either.

The north-east of Scotland was known as ‘Hellfire Corner’ due to its part in the Nazis’ tactical campaign of terror.

This part of Aberdeenshire sustained nearly 70 air-raids.

The fishing communities dotted along the coast were well-placed for Germany to target from its air force bases in Norway.

Where the rock meets the sea at the most northernly point of the Banffshire coast sits Portknockie.

It was a community once buoyed by a busy herring fishing industry and served by the railway.

This made it an easy hit for enemy bombers heading from Norway en route to more lucrative targets down south.

Portknockie School Janitor raised alarm of Nazi air-raid

Portknockie residents were fairly accustomed to the hum of a Spitfire or Hurricane passing over Portknockie.

Local man and pilot James Murray often flew over the village.

But on February 19 1941, it soon became apparent this wasn’t the familiar sound of a Spitfire engine.

It was a Junker JU-88 – a Luftwaffe, twin-engined killing machine.

Joe Pirie, then 18 years old, was assistant janitor at Portknockie School and had been working in the playground when the plane appeared.

He said: “I saw the plane coming nearer the school, it flew just above the chimneys.

“It was so close I felt I could touch it. It was only then I saw its black cross.

“I just ran into the school and set off the alarm bells.”

The raider turned its machine guns on the school, the strafing bullets smashing the windows.

Pupils ducked under desks to hide from bullets

On the other side of those windows were hundreds of children who were suddenly face to face with the perils of war.

What started out as a “quite dull” day in the classroom for young Bert became an unforgettable experience.

He documented the incident as an elderly man in his 80s before his death. Now his son Stuart is keen Bert’s story is told in his own words.

Bert said: “The air-raid siren went off and the teacher Miss Watson shouted ‘duck under the desks’.

“For a moment, I wondered how a duck managed to get under the desks.

“There was a pitter-patter, nothing unusual, it was always raining up there.

“However, I soon discovered Mr Hitler had found me.

“His bombers were strafing my school with machine gun fire, rat-tat-tat, the planes flying just above rooftop height as they went on to attack a goods train in a siding by the railway station.

“The windows of the school were shattered by bullets, yet none of the teachers or pupils were hurt.

“The devils had already shot up a stationary train.”

Portknockie School playground was sprayed with bullets

Mr Moyes, headmaster of Portknockie School, marshalled all the pupils – more than 350 of them – to the air-raid shelter while the plane was still roaring overhead.

It was reported that the children “maintained perfect discipline” and marched from the school to the shelter as if they were on ordinary training.

The plane was so close to the school that a resident eyewitness saw its wing clip the chimney of the schoolhouse next door.

Mr Moyes said: “I remarked to one of my assistants, ‘I think that is a Jerry overhead. We had better get the children to the shelter’.”

He told the P&J how the playground was “sprayed with bullets”.

The enemy plane, with its foreboding black crosses under its wings, was still circling in the vicinity like a hawk circling its prey.

‘Gas masks on and cotton wool for our ears’

With fears it would round on the school again, the staff and pupils sought shelter.

Mr Moyes said: “Some windows were broken, but nobody was hurt.

“After that, I had the children marshalled, and they marched in orderly fashion to shelter.

“It was after that that the raider returned and dropped his bombs.”

By now, young Bert was in the makeshift shelter.

He explained: “We children had received training in what to do during an air-raid – gas masks on, cotton wool for our ears, and a bit of rubber between our teeth.

“There was a shelter nearby, a small, roofless blockhouse inside another building.

“The town council did not want to waste money on such things, and maybe thought the enemy were so far away and were never going to bother us.”

Three civilians killed in Portknockie bombing

The passengers on the stationary bus which was attacked took shelter in nearby houses.

But when the plane wheeled around again, casting its sinister shadow over the village below, it returned to dropped bombs.

It is believed the goods train in the siding at Portknockie Station was the real target – belching out black smoke, it caught the eye of the pilot.

He dropped a bomb by the railway, but it didn’t explode, and was later detonated by the bomb squad.

However, the second bomb missed the train and hurtled through a gap in the buildings before landing and exploding in the yards between 8 Seafield Street and 9 Admiralty Street.

Bert’s wartime home was just a few doors down at 12 Admiralty Street.

Three people were killed while just going about their every-day routine.

Margaret Ann Mair aged 16; her father James Mair aged 51, who was on leave, and their neighbour Annie Mair Mackay.

Annie was returning to her house after hanging up washing when she was killed. Margaret had been peeling potatoes at 8 Seafield Street.

Nine houses were badly damaged, a further seven civilians were seriously injured, with many more slightly hurt by flying splinters and debris.

Mr Mair’s son said: “I was in my bed at the time the bomb dropped, and I escaped injury.

“My grandfather, who was upstairs, went down the stairs shouting ‘are you all right?’ but on reaching the back door he found my father and sister both killed.

“My mother, who was also in the house, escaped injury.”

‘Passengers dived to floor of train compartments’

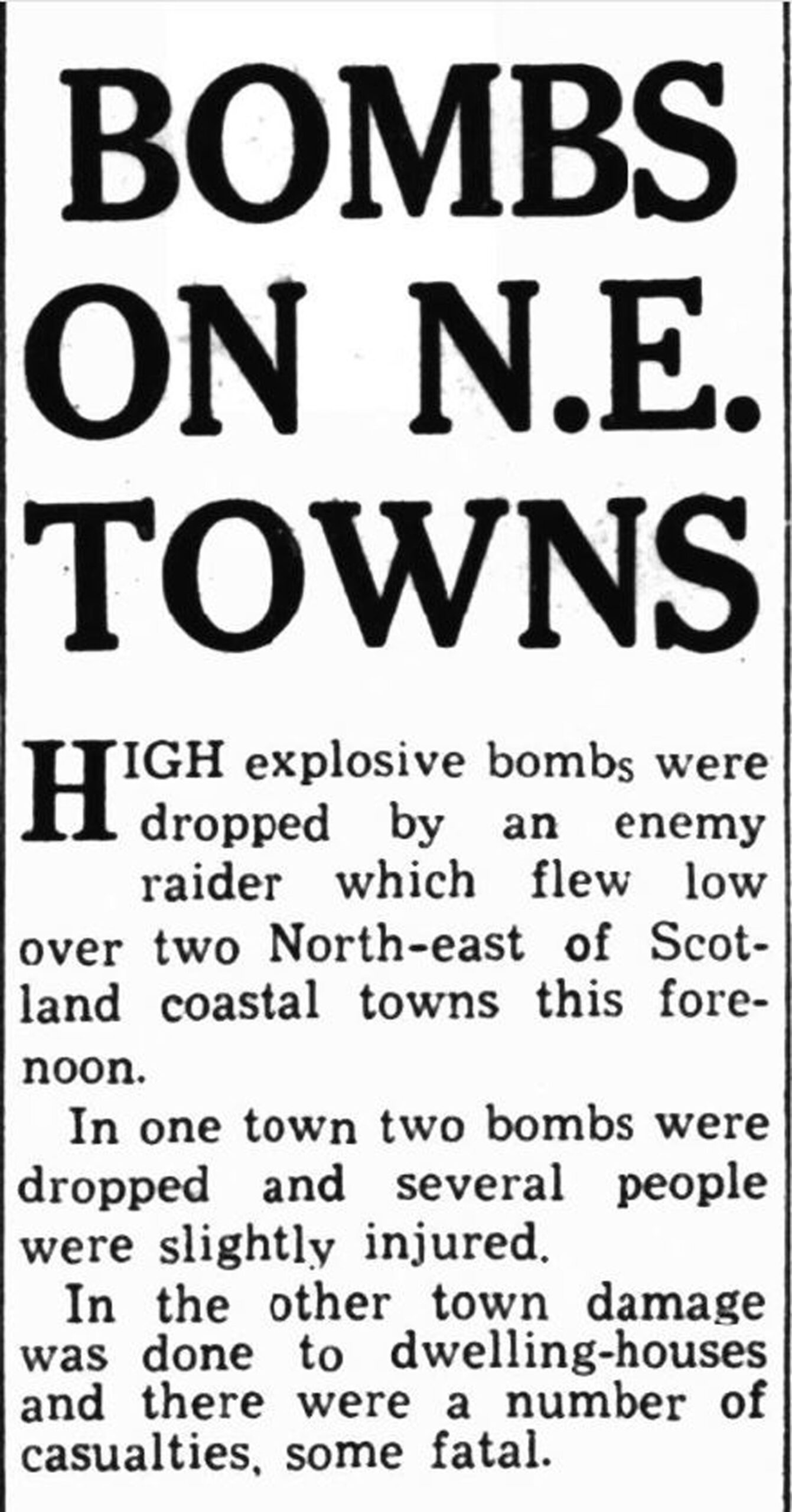

A brief report in the breaking news column on that day’s Evening Express front page read: “Details of north-east raid today show that raider machine-gunned streets of first town without success.

“At another town school and bus machine-gunned. Children were in shelter and bus passengers dived for cover.

“Raider then wheeled over another part of town and dropped bombs. Number of houses partially demolished. Three persons killed and others slightly injured.”

Later that night, enemy planes were active once again on the Moray Firth coast, this time targeting Portsoy.

A plane made three swoops on a passenger train, people dived to the floor in the compartments, but there were no casualties.

The train, which did not stop, was attacked when rounding a bend.

Portknockie School raid caused ‘friction’ between officials

The planes escaped back to Norway having left death and destruction in their wake on that fateful February day.

The raid led to “friction” between Portknockie Town Council and Air Raid Precautions authorities regarding first aid equipment in the town.

They probably realised the death toll would have been considerably higher had Portknockie School been bombed.

The council was concerned there wasn’t enough aid available in Portknockie and that there was too much reliance on outside help.

Particularly as enemy aircraft weren’t strangers to the coastal community.

On another occasion, young Bert recalled a plane being shot down by anti-aircraft defences, likely Portknockie’s machine gun post.

It landed in a field, while another plane ended up in the sea.

Propeller of German bomber dredged from Moray Firth

In 2016, fisherman and diver Brian Donaldson found an engine and propeller in Cullen Bay near Portknockie.

He lifted the engine and towed it back to shore with his fishing boat.

Aviation experts concluded it was indeed the engine of a Junkers aircraft.

The victims of the 1941 are remembered in a memorial plaque, which was unveiled in 2012.

After escaping his time in Portknockie unscathed, Bert returned home to his mother.

He said: “When I got home to Edinburgh, my mother said to me ‘well son, it may have been too quiet for you in Portknockie, but I am glad you got evacuated away, safe from all the bombing’.

“I never told her that the Germans found out where I was.”

Bert’s birthday trip to Portknockie

Bert returned to Portknockie from Edinburgh in 2015 with his sons to mark his 82nd birthday.

When son Stuart booked the hotel and mentioned the reason for the family’s trip north, word soon got around.

Bert was invited to speak at Portknockie School nearly 75 years after his memorable afternoon under fire from the Nazis.

Stuart said: “He was a man of humour so I imagine those kids were highly entertained.

“He was pleased that while waiting at the bus stop while trying to get back to the train station, kids on bikes came up to him to ask more question.

“He was so taken by the warm welcome that the people of Portknockie gave him for the second time around.”

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

Conversation