On this day in 1929 Aberdeen residents were enjoying watching a drama unfold just offshore.

The drama would keep them entertained for many more months.

The 1905 steamer SS Idaho had arrived a couple of weeks earlier, and in dense fog had missed the entrance to the harbour, stranding on a sand bank 150 yards from shore in full view of the populace.

Idaho was built 1903 by Earles Shipbuilding & Engineering Co, Hull for Thos Wilson, Sons & Co.

She was owned by the Ellerman Line of Hull, and was on passage from Hull to New York.

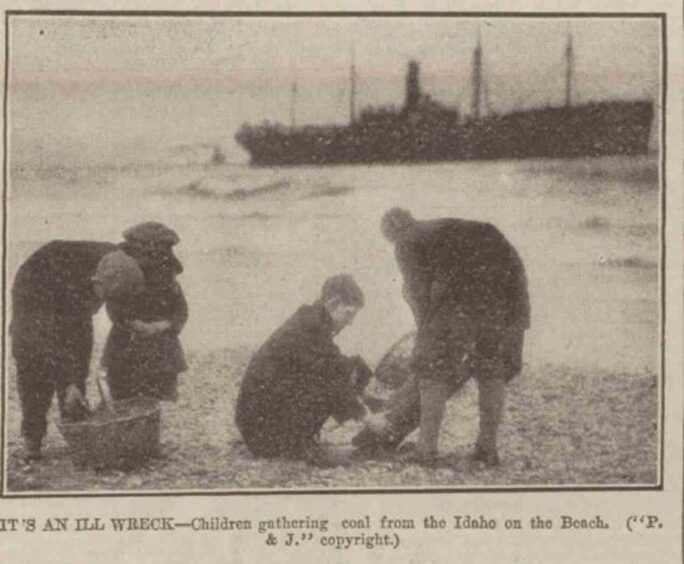

Being a steamer, she was carrying a vast amounts of coal, and this was naturally of considerable interest to Fittie residents.

Bad weather blighted all attempts to reach the ship for several days after she stranded on January 7.

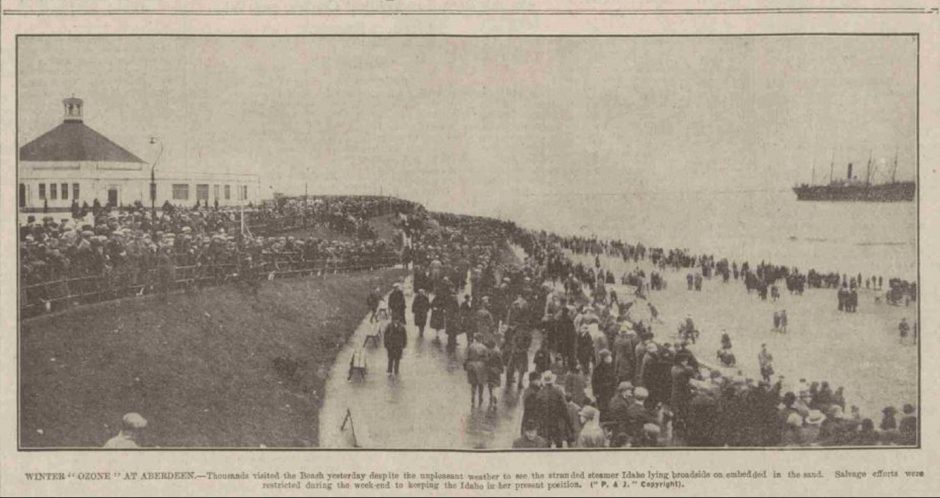

Once the fog cleared on January 10, residents got a good view of the stranded SS Idaho. The image above includes glimpse of the dance hall, described at the time as ‘much discussed’.

‘Weird in the extreme’

Once the fog had finally cleared, the Aberdeen Daily Journal, reported the scene at Aberdeen Beach, describing it as ‘weird in the extreme’.

The reporter was prompted into full poetic flow by the weirdness, writing: “The hazy gleam of the moon cast a cold radiance over the deserted wastes of snow-mantled sands, while across a dark strip of water loomed the black hull of the vessel. A biting wind blew from the north-east. No movement could be seen aboard the steamer, but red lights showed from her mastheads.”

After his lyrical outburst, the reporter managed to gather himself to describe the first attempts to get the cargo off.

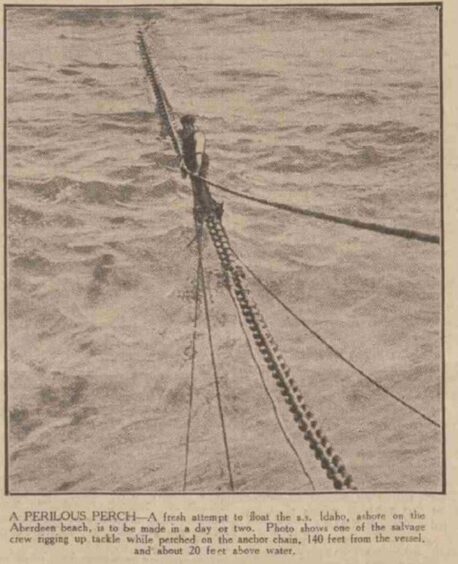

“Yesterday, despite the handicap of blinding snow and intense cold, work was commenced in rigging up a ‘blondin’ from shore to the masthead.

System put in place to unload cargo from SS Idaho at Aberdeen Beach

Blondins are essentially ropeways with a mechanism to raise and lower loads vertically from the suspended ropeway. This allowed them to cross wide, deep spaces such as quarries, or in this case, ocean, and move material up to the ropeway and across to the edge of the quarry or dry land.

Curiously, blondins had a strong north-east connection, being invented by Scottish quarry engineer John Fyfe. He had installed the first example in 1872 at Kemnay granite quarry at Garioch.

With SS Idaho, the idea was to try and get the ship’s cargo taken off to make her easier to refloat.

“The erection of this aerial cableway will, owing to the elaborate arrangements necessary, take some time to complete,” wrote the P&J reporter. “Members of the salvage party on the beach expressed themselves quite confident of getting the Idaho off in due course.”

This was more the triumph of hope over adversity.

Early on in the proceedings, Idaho’s master, Captain C Barron, was brought ashore.

A strong man was enlisted to carry him piggy-back through the shallow water onto the beach.

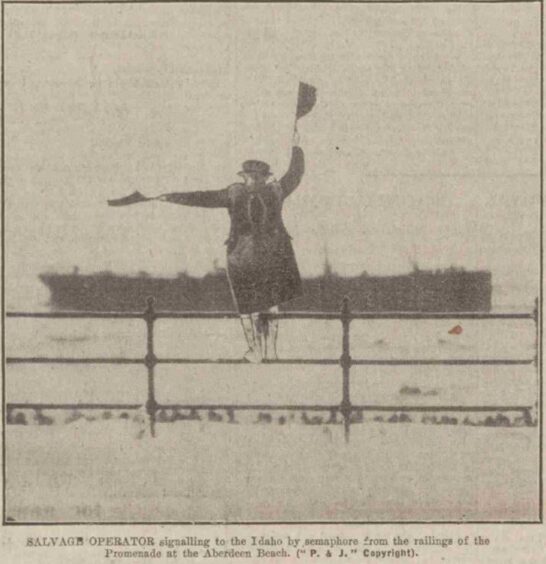

Communication was by semaphore from the shore.

Unloading the cargo

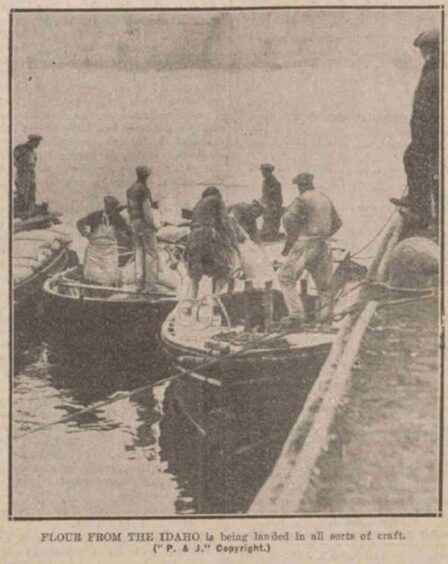

As soon as possible, it was all hands to the pump to unload the cargo. It’s not clear exactly what the cargo comprised at this point, but it certainly included flour.

By January 24, the weather had improved and unloading the cargo was in full swing.

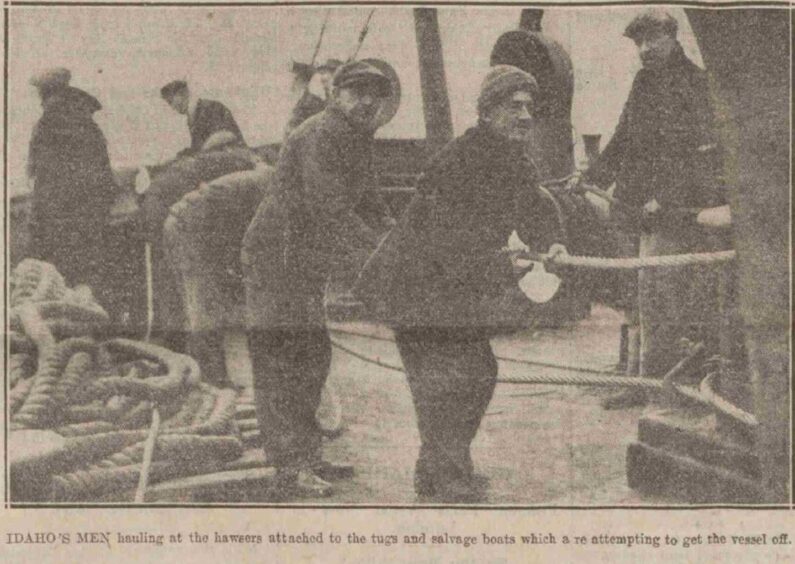

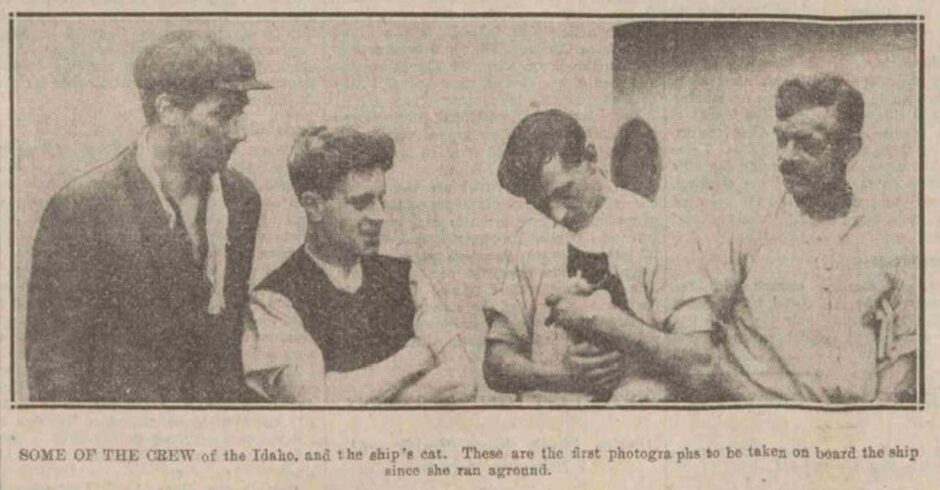

The P&J reported that Idaho’s crew had been taken off by salvage boats, apart from five engineers, retained to help the salvage crew.

The crew were paid off and left Aberdeen, bound for Hull to take up work on another of Ellerman Line’s vessels.

They had been in isolation aboard Idaho for 17 days, during which time they had been looked after by the port missionary, Mr McDonald, pictured above with the captain, whom they made a point of visiting at the Sailor’s Home before they left.

A weather window at this time permitted a multitude of small boats to swarm around Idaho to help take off the cargo.

Fishing boats joined in efforts to unload SS Idaho

Fishing boats from Montrose and Peterhead joined the effort.

The P&J reported: “It is expected that given the good weather, even more vessels will be engaged in unloading the Idaho today. Everything is proceeding at top speed to lighten the steamer sufficiently to enable a special effort to be made by the tugs on Sunday, when there is a high tide.”

But refloating of SS Idaho didn’t occur until July

As it turned out, they didn’t manage to refloat Idaho until July of that year.

It was September before she finally left Aberdeen, under tow from two steam tugs.

Death knell

But the incident proved her death knell and she was finally scrapped in 1930 at Port Glasgow.

Possibly the most interesting part about this drama was what was alleged to be happening onshore.

Did Fittie residents appropriate the coal?

The only mention in the papers of the coal aboard the Idaho was through this image of children gathering it from the shore shortly after the vessel stranded.

But Fittie residents considered they had something of a claim on her cargo, and legend has it that large quantities of coal would later be found stashed everywhere possible in the neighbourhood.

Eventually the game was up and the residents were made to give it all back, apart from one container which they were allowed to keep.

But this aspect of the drama not being reported in the press, facts are elusive , so if any readers can throw better documented light on the proceedings, please contact susy.macaulay@pressandjournal.co.uk

You might enjoy:

On This Day 1939: Fraserburgh trawler bombed in North Sea