At the height of World War Two, an Easter Ross man living in Germany broadcast Nazi propaganda to Britain on ‘Radio Caledonia’.

Donald Alexander Fraser Grant, from Alness, has been dubbed Lord McHaw Haw after that legendary traitor and propagandist, American-born William Joyce.

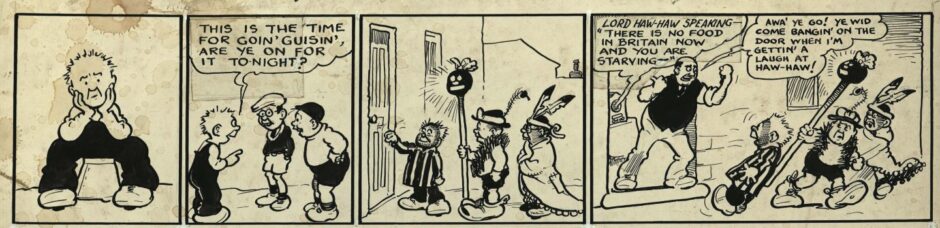

Joyce’s faux snooty voice on his ‘Germany Calling’ broadcasts earned him the soubriquet Lord Haw Haw.

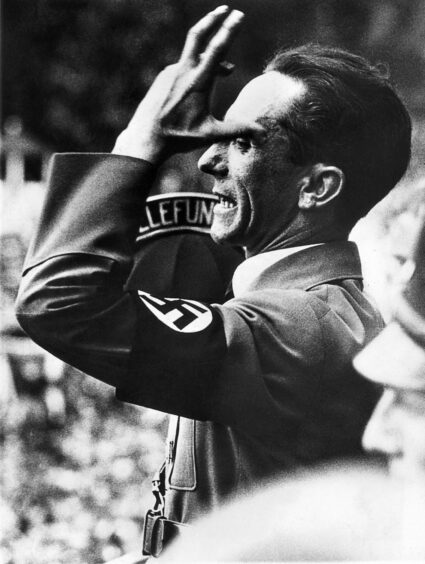

Radio Caledonia was one of many ad-hoc radio stations created and controlled by the Nazi propaganda machine, masterminded by the notorious Joseph Goebbels.

Donald Grant, born 1907, was a rather ordinary Hoover salesman from a family of shop-keepers.

He attended Dingwall Academy, leaving at 16 to work in a woollen mill in Bradford.

He was in London in the 1930s, and was known to be an anti-semite, involved with the British fascist movement.

Letters to senior Nazis

He wrote letters to senior Nazis in Germany. They were intercepted, and one was found requesting literature on ‘the physical training of women in the new Germany’.

Another letter to a German official includes the phrase ‘Perish Die Juden’ (Perish the Jews).

Upon the outbreak of war in 1939, he found himself in Germany, apparently having written to the German Foreign Propaganda department the previous year, looking for a Nazi female penpal. He seemed to have a bit of a thing for Teutonic women.

Before long he came to the attention of the Reichstag’s Ministry of Propaganda, hungry to recruit native English speakers. After all, Nazi propaganda wouldn’t be at all convincing if spoken by presenters with heavy German accents.

He travelled to Hanover to meet Hélène Jirka, an attractive young fascist, who recruited him for a new short wave propaganda station, Radio Caledonia.

Incidentally, MI5 officers who interviewed Jirka after the war, said “a tougher and less pleasant example of Nazi humanity could hardly be conceived.”

Low point in the war

Broadcasting under the name of Donald Palmer, Grant started his work in June 1940, a low ebb in the war for the Allies.

Back home, his parents in Alness were apparently unaware of what Grant, whom they called Derrick, was up to.

But it later transpired through police inquiries that Grant’s mother had told the local doctor’s wife that “Derrick was very avid on the German Nazis.”

Divide and rule

Grant’s message was intended to divide the populace by telling anyone who would listen (few admitted to listening) that Scotland was fighting a capitalist, imperialist war, a war orchestrated by the Jews.

But unlike Lord Haw Haw, William Joyce, Grant didn’t stick to the Nazi line of denigrating the British state.

Joyce went to the gallows after the war, Grant was spared. Perhaps this is why.

He eventually realised that the station was serving no useful purpose, and was allowed to stop broadcasting after two years.

Civil Renegade No. 22

After the war he found himself number 22 on a ‘Civilian Renegades Warning List’, but managed to evade capture for more than a year.

Eventually he gave himself up, and was seen by the War Office as “a pathetic figure, now reaping the the fruits of illegal and misguided actions.”

Professor Jo Fox of the University of London is a specialist in the history of propaganda, rumour and mis- and dis-information.

She has had the opportunity of seeing the transcripts of Donald Grant’s broadcasts, stored amid thousands of wax cylinder recordings and other transcripts in a massive hangar-type of building at the Imperial War Museum at Duxford.

Trying to drive wedge in union

She said: “When you look at Grant’s transcripts, it’s about Scotland first, playing to the sense of Scottish identity, trying to drive a wedge in the union because the Germans wanted to fragment the country.

“The more you fragment, the more you fracture the body politic, the more chance you have of disrupting the war effort.

“When people are willing to fight, you try to disrupt their willingness by focusing their loyalty.

“It didn’t happen.

Propaganda tactic didn’t work

“No matter how strong the nationalist feeling was, people didn’t want to lose the war and be occupied.”

Jo points out that these are very standard propaganda techniques, and she gets the sense that Grant wrote them very much under the eye of the Nazi machine.

“He wasn’t a talented, instinctive propagandist like William Joyce,” she said.

And she warns that we all tend to think that everyone else is susceptible to propaganda, but not ourselves.

“It’s not true, even for myself,” she said. “What makes you susceptible to propaganda are your deeply held pre-existing beliefs.

We’re all susceptible to propaganda

“That is why Scottish national identity can be a very powerful one to enact.

“If you believe deeply in Scottish independence, then a propagandist could come right into that space.

“It’s something you hold as intrinsic to your core.

“Religion, identity, deeply held political beliefs, you’re not going to move them, and propagandists can work with that very neatly, enabling you to strengthen your core beliefs.

“That is the area where people are most vulnerable.

“I’m just as vulnerable as the next person”

“I’ve studied this now for thirty years and I consider myself to be just as vulnerable as the next person because I’m human and hold pre-existing beliefs.”

So what impact, if any, did Donald Grant have with his attempts to drive a wedge in the union?

Jo thinks not a lot.

She said: “We can’t say what the effect was, but the government kept everything and he doesn’t register in any of the records of mass observation, whereas Haw Haw was a personality and the main man.”

Donald Grant’s impact was mainly at home in Alness

Sadly, Grant’s main impact was in his home town of Alness.

Jo Fox visited the town almost a decade ago, and was able to take the temperature there, nearly seventy years after the war.

She found some raw nerves still in the town at that point.

She said: “They were very conscious that one of their own was involved in this, and it’s still in the town a little.

“His family had a difficult time, particularly in the aftermath of the war.

“For a documentary for Radio 4 we talked to someone who knew him and the family and they described very clearly the feeling of the community because they had people servicemen stationed there, the Air Force.

Feelings of shame

“This was one of their own and they were very committed to the war effort and they thought this was shameful for the town.

“When it became known, the family’s greengrocers shop had its window smashed.

“The only person who remembers him as being a slightly odd kid- but was that in retrospect, because he went on to be quite odd.

“The family probably not like that.”

But whereas Willam Joyce was executed as a traitor after the war, Grant managed to slither free having persuaded the court he was a pacifist working in the cause of peace and coming over as somewhat pathetic.

Jo has her own doubts about the court’s decision.

She said: “What the judge says is – and there is a question mark in my own mind over this- ‘we don’t think you were doing this because you were a Nazi sympathiser, necessarily’, although there was a lot of evidence that Grant was involved with the British Union of Fascists.

Court gave him benefit of doubt

“That was known, but the court decided that he apparently ‘didn’t intend to do damage’.

“I think it’s a very generous interpretation because if you trace back Grant’s trajectory there is evidence of sympathising with fascist cause, alignment with Mosley.

“Grant spins a story that all he was trying to do was trying to broker a peace for the Scottish people, why should the Scottish people fight a British war? We need to broker a peace and a separate peace for Scotland.

“He used that line as his defence in court, and the court finds it plausible but I do think there is plenty of evidence in Grant’s background that point to more fascistic leanings.”

Grant was jailed for six months at the Old Bailey in 1947 for assisting the enemy.

Afterwards, he returned to help run the family shop, but fled to London after it was attacked.

South Africa was his next destination, but he’s thought to have returned to London, dying there in the 1980s.

You might find this interesting:

How a Cruden Bay farmer’s wife welcomed enemy submariners with a cuppa in 1945