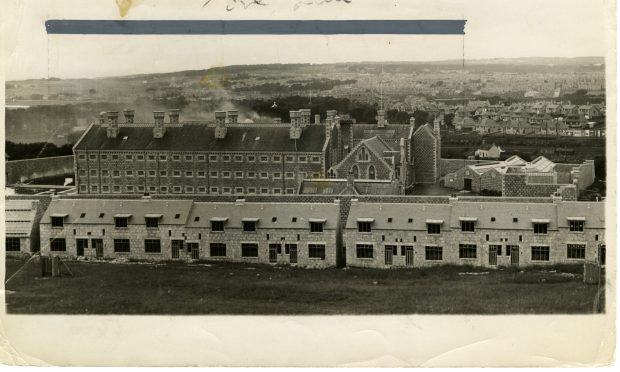

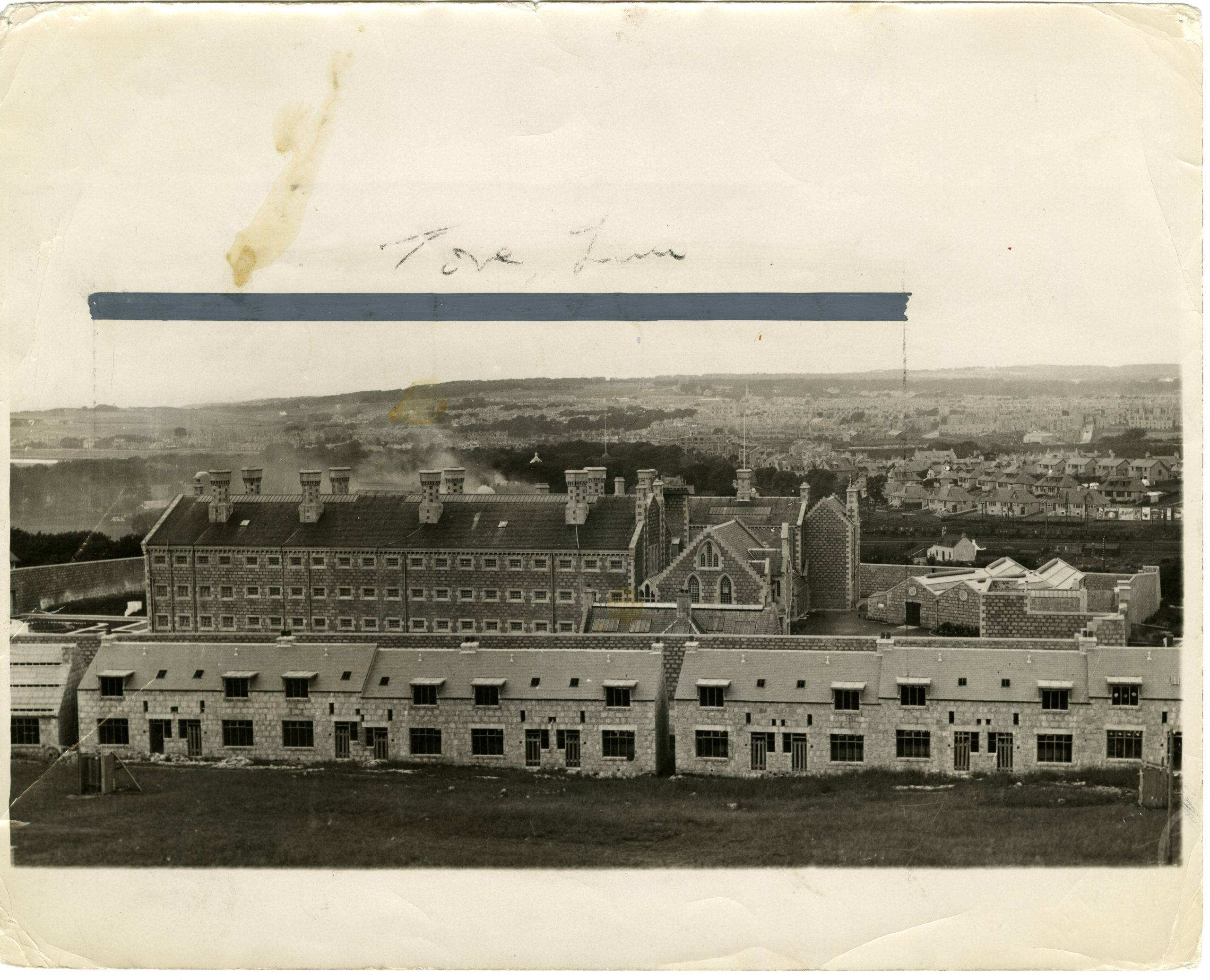

Craiginches Prison was an Aberdeen institution most people hoped never to become acquainted with, but one that loomed imposingly over the city for 123 years.

Now, a decade on from its closure, we take a rare peek behind the prison walls at the photos and stories of yesteryear.

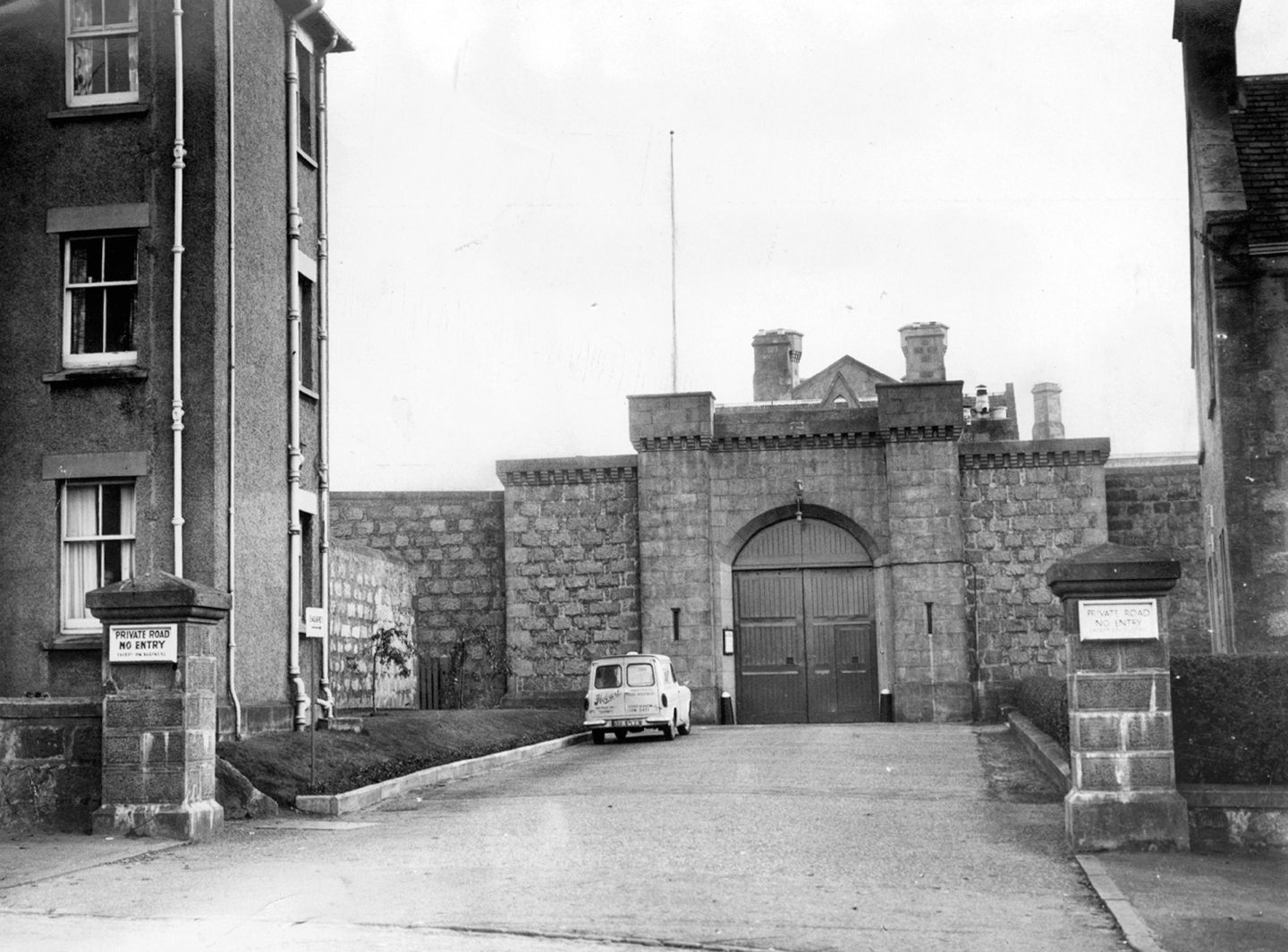

With its unwelcoming, towering fortifications alongside Wellington Road, it was every inch the Victorian prison.

Craiginches opened in May 1891 and prisoners moved from Lodge Walk in the city centre to their new home on June 9.

For 123 years, it housed hardened criminals, and was the location of a particularly controversial chapter in the history of Aberdeen – the hanging of Henry John Burnett, the last man to be executed in the city and in Scotland by the state.

But in January 2014, it closed down and prisoners transferred to HMP Grampian, Peterhead’s new super prison, which carried on the community-facing ethos established at Craiginches.

We’ve gone through our archives to uncover all sorts of fascinating, illuminating, and downright bizarre stories and photographs of life at Craiginches.

Earl’s brother nearly ended up in Craiginches

The prison first made national headlines in 1895 when English aristocracy nearly ended up within its confines.

In October that year, a group of men were charged with cycling without lights near Banchory.

Among them was the Honorable Mr Everard Feilding, brother of Rudolph Feilding, the 9th Earl of Denbigh.

Each man was fined 5 shillings with the alternative of three days’ imprisonment.

Mr Feilding “was anxious to see the interior of a Scottish prison” and declined to pay his fine such was his desire to go to prison.

He was taken to Banchory Railway Station, travelled to Aberdeen and was escorted to Craiginches.

But when he reached the prison, the P&J reported “later intelligence states that Feilding did not carry out his resolution”.

Adding: “He journeyed to Aberdeen, but, after having had a look at the exterior of Craiginches Prison, he paid the fine and returned home.”

Craiginches’ revolutionary approach to rehabilitating prisoners in 1940s

No wonder; in the 1890s, the prison contained men whose gruesome crimes included desecrating graves and mutilating bodies at the city’s cemeteries.

But as the prison moved into the 20th Century, the harsh Victorian programme of crime and punishment gave way to rehabilitation.

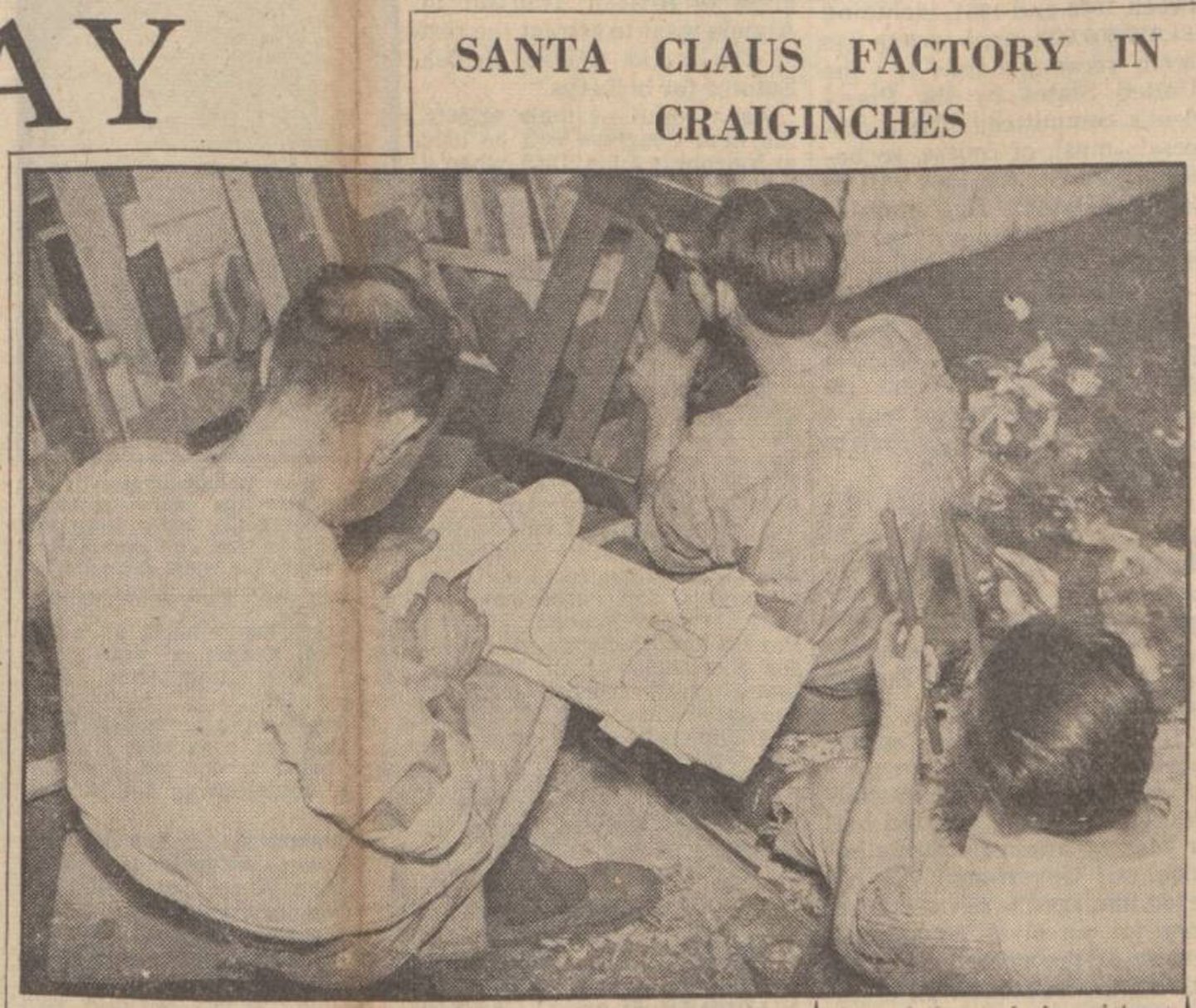

In 1947, Craiginches Prison governor John Peddie introduced a scheme where prisoners made toys for sick children at the children’s hospital.

The response from prisoners was described as “phenomenal” and led to evening classes, social gatherings, hobby groups and sports teams being established.

Mr Peddie explained the enlightened outlook in prison was to “fit the prisoner for his return to normal life by giving him a trade, a hobby and all the interests of a good citizen”.

The initiative was described as a stark contrast to the days of the “rule of silence” when a prisoner might go days without speaking or hearing a word, apart from an order.

Craiginches’ revolutionary approach saw inmates who had no trade, very few did, learn the basics of plumbing, joinery, smithing, netmaking and cooking.

Prisoners would earn money for their work, which could be spent on magazines, tobacco or savings stamps.

For many, it was their first time earning an honest living.

Governor Peddie was ‘disciplinarian with a heart’

The council’s education committee provided teachers for night classes, with special lessons for “backward pupils” to learn general English, arithmetic and geography.

Two evenings a week were dedicated to recreation like board games or reading, while well-behaved men were allowed to watch films or newsreels.

Every Sunday was chapel day and on November 9 1947, for the first time in the history of the prison, 17 inmates took communion.

Governor Peddie was also planning pre-apprenticeship courses and basketball league competitions.

With 30 years’ experience as warder, chief officer and governor at Barlinnie, Peterhead Polmont and then Craiginches prisons, he was known as a reformer.

He was “a disciplinarian but with a heart and an ideal in citizen-making”.

And it was his belief that the happy hours prisoners spent carving Christmas presents for hospital patients was also the prisoners carving out futures for themselves.

Aberdeen man used to break into Craiginches every Christmas

While most people would be keen to avoid jailtime, one Aberdonian made it his mission every Christmas to get himself banged up.

“Cherry” Rae – so called because of his rosy face – would get his festive feed by breaking into prison.

The 62-year-old used to break a little law each year hoping to get 14 days’ imprisonment at Craiginches – and a three-course meal.

Sometimes he’d pretend to be homeless or begging, and be charged with vagrancy.

Speaking in 1957, after 12 years of successfully breaking in, he said: “I have no intention of staying there for long – just long enough for the dinner and a chat with some of my old pals.”

He added: “The warders are kind and the spirit is good. As for the big turkey dinner – I doubt if you’d get it in a restaurant for less than 12s 6d.

“And there’s always plenty of it.”

Cherry explained he wasn’t a bad man, just his yearly prison visits “meant a lot” to him.

There were more hijinks at Craiginches in 1958 when a student was lowered behind the prison walls overnight.

Aberdeen University students were preparing for Charities’ Week when 17-year-old Nicholas Johnson failed to provide tinfoil he had promised.

As a forfeit, he was taken from his bed in pyjamas by a party of students, bound and gagged, and driven to Craiginches.

They propped a ladder against the wall and lowered him down the other side on a length of rope.

Young Nicholas spent the rest of the night in a police cell.

Execution was darkest chapter for Craiginches

But the 1960s saw perhaps the darkest episode in the prison – and Aberdeen’s – history when Henry John Burnett was hanged there.

The 21-year-old was sentenced to death for a crime of passion.

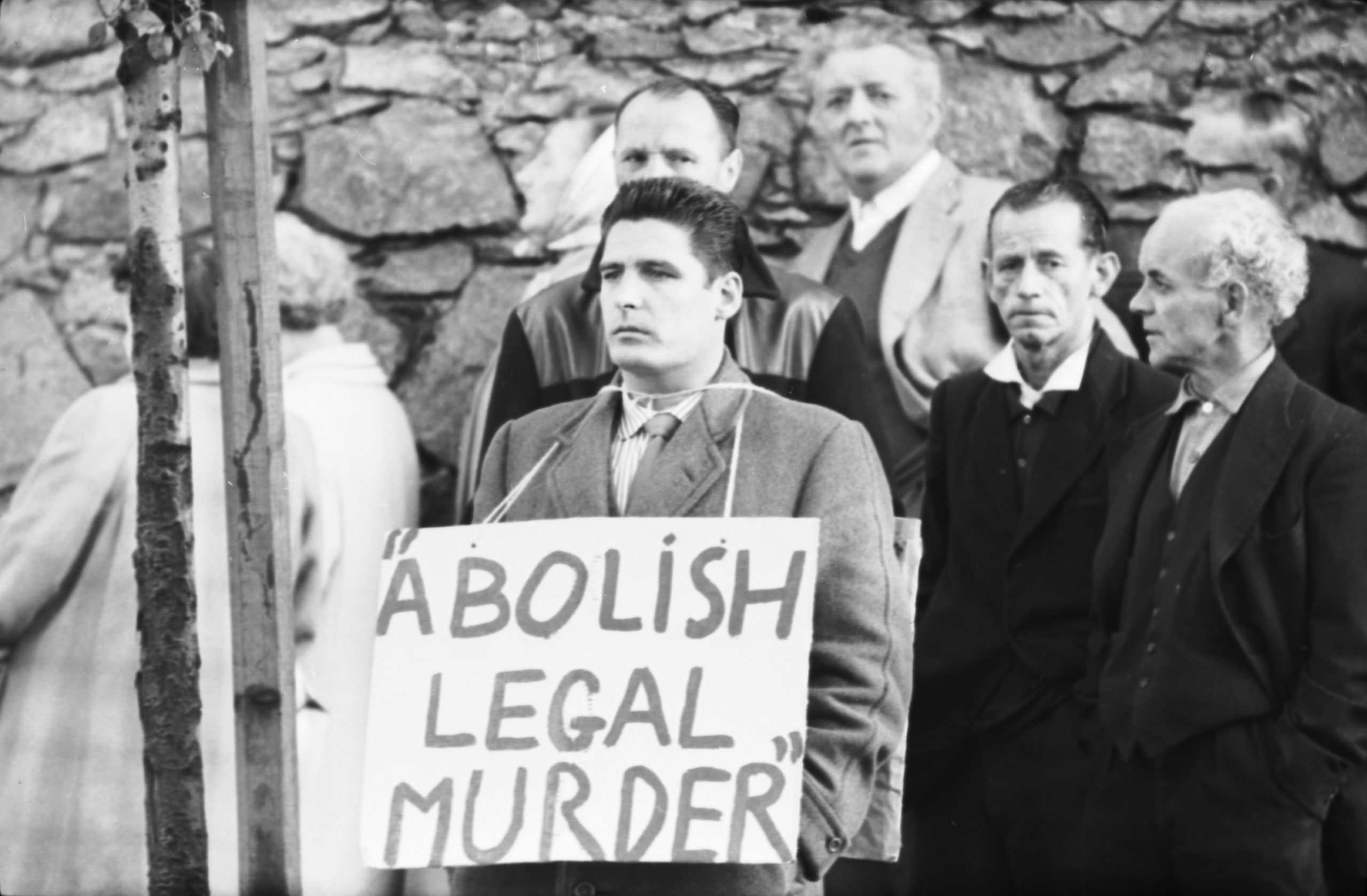

Aberdonians were outraged – he was mentally unwell and other murderers whose crimes were premeditated weren’t executed.

Despite desperate campaigning, Burnett was hanged at 8.01am on July 25 1963.

He made history as the last man to hang in Scotland and was buried between the pit room and staff toilets.

It would be another 50 years before his body was exhumed and buried.

The story of Craiginches Prison from the 1960s until its closure will be continued in part 2 tomorrow.

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

Conversation