While the early years of Craiginches were dominated by Victorian crime and punishment, prisoners began to challenge their conditions as the decades passed.

The notion that prisoners should be isolated with only a Bible for company and God to answer to were out of date by the 1960s.

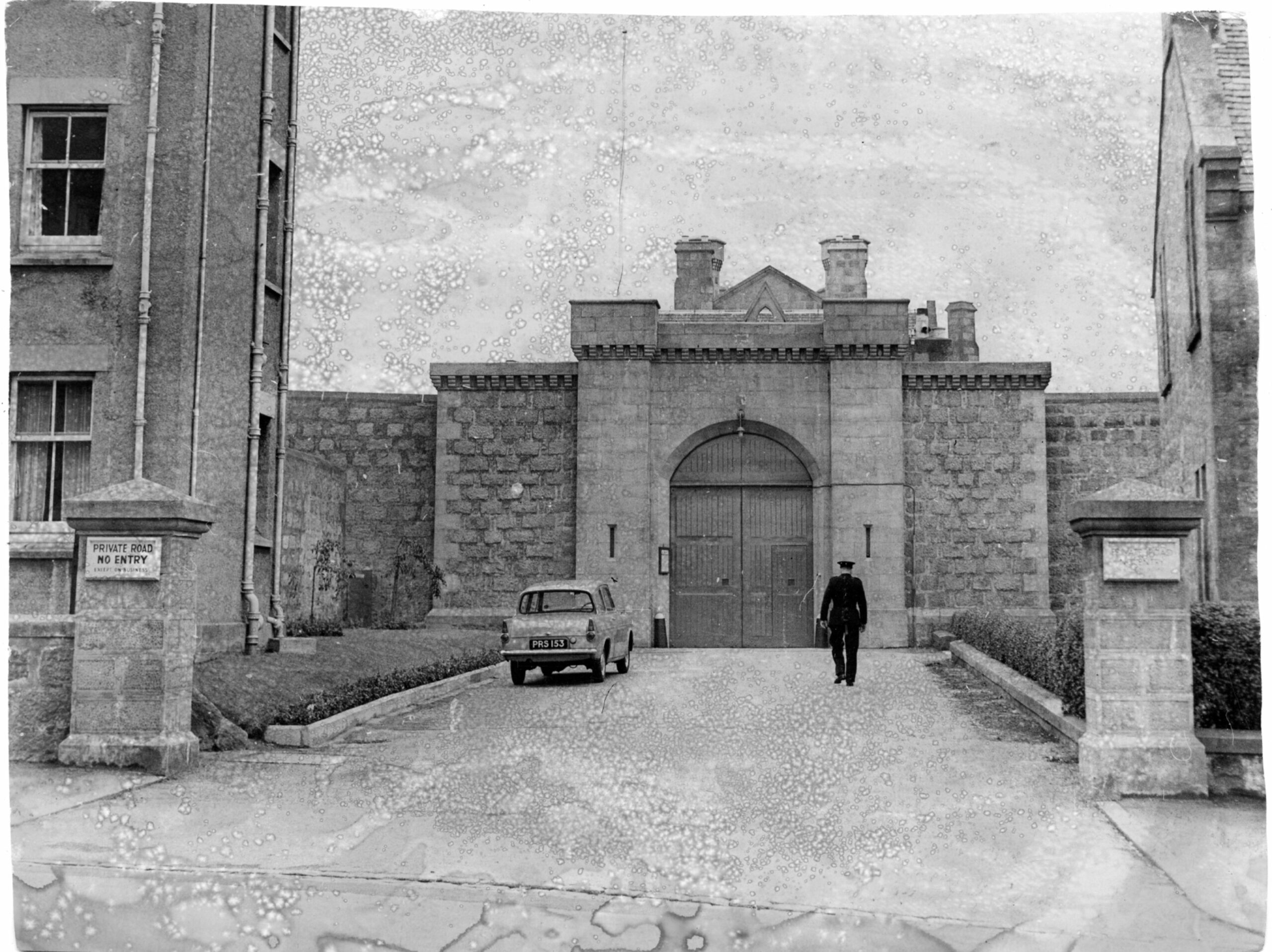

Following our look at the first 60 years of Craiginches yesterday, we now turn to its final decades which were dominated by demonstrations, and ultimately, demolition.

Prisoner scaled chimney and enjoyed a cigarette above 50ft drop

In 1967, Craiginches made front-page news when a prisoner’s protest saw him scale the jail’s roof.

Captured in a now-iconic photo, it was to be the first in a long-line of sit-down protests.

The escapade on March 21 saw the inmate smash several skylight windows before making his way up to the precarious heights of the chimney stack – the highest point of the roof.

Sitting with his legs dangling over a 50ft drop, he laughed at a prison officer who tried to persuade him to leave his perch.

The EE reported how the man “was obviously enjoying himself and waved at passers-by in Grampian Place”.

The reporter at the scene said: “A strong wind buffeted his back and he held one of the chimney pots for support.

“Wearing drab, greenish prison uniform, with a green jumper and blue socks, the prisoner seemed to be enjoying his escapade – he smiled frequently at occasional passers-by and several times gave the thumbs-up sign.”

A poor, “grey-haired” prison officer had to make his way out of a skylight to try to convince the prisoner to go back inside.

He was joined by more wardens, but the prisoner shouted “don’t bother, lads”, before casually lighting up a cigarette.

After a three-hour stand-off, and more exchanges between the prisoner and staff, an officer disappeared back into the building, reappearing with a small package.

He handed it up to the inmate and shouted: “I’ve played ball with you, now you play ball with me.”

The prisoner jumped from his perch and jauntily clambered across the roof and back through a skylight.

When Craiginches prisoners took part in nationwide rights protest

The hijinks continued in 1972, when nine prisoners made their way onto the roof at Craiginches.

The summer of ’72 was a tumultuous one for the prison service in the UK when there was more than 130 protests nationwide.

The headlines were dominated by prison protests sparked by the establishment of a prisoners’ rights organisations Preservation of the Rights of Prisoners (PROP).

It was effectively an unofficial trade union for prisoners.

On September 1, Craiginches inmates climbed onto the chapel roof where “they rang the prison bell, waved a Union Jack flag and played a transistor radio”.

But warders simply ignored them until they came down.

The previous day and night, 170 prisoners had staged a protest on the hospital roof at Peterhead Prison.

Brandishing a PROP banner, they chanted: “We want better conditions. We want an answer. Let the press in.”

Prisoners making their voices heard in the north-east of Scotland, were joined by those the length and breadth of the UK.

Down south, inmates took to the roofs of Wormwood Scrubs, Dartmoor, Albany Prison on the Isle of Wight, Cardiff, Liverpool – and almost every prison in between.

What began as peaceful, sit-down protests seeking better conditions descended into riots, breakouts, take-over bids and even fires at some English jails.

Ultimately PROP wasn’t taken seriously by the Home Office and collapsed into in-fighting, while prisoners who played roles in riots were seriously reprimanded.

However, inmates did successfully shine a light on inhuman conditions at some prisons.

New opportunities for prisoners in 1970s

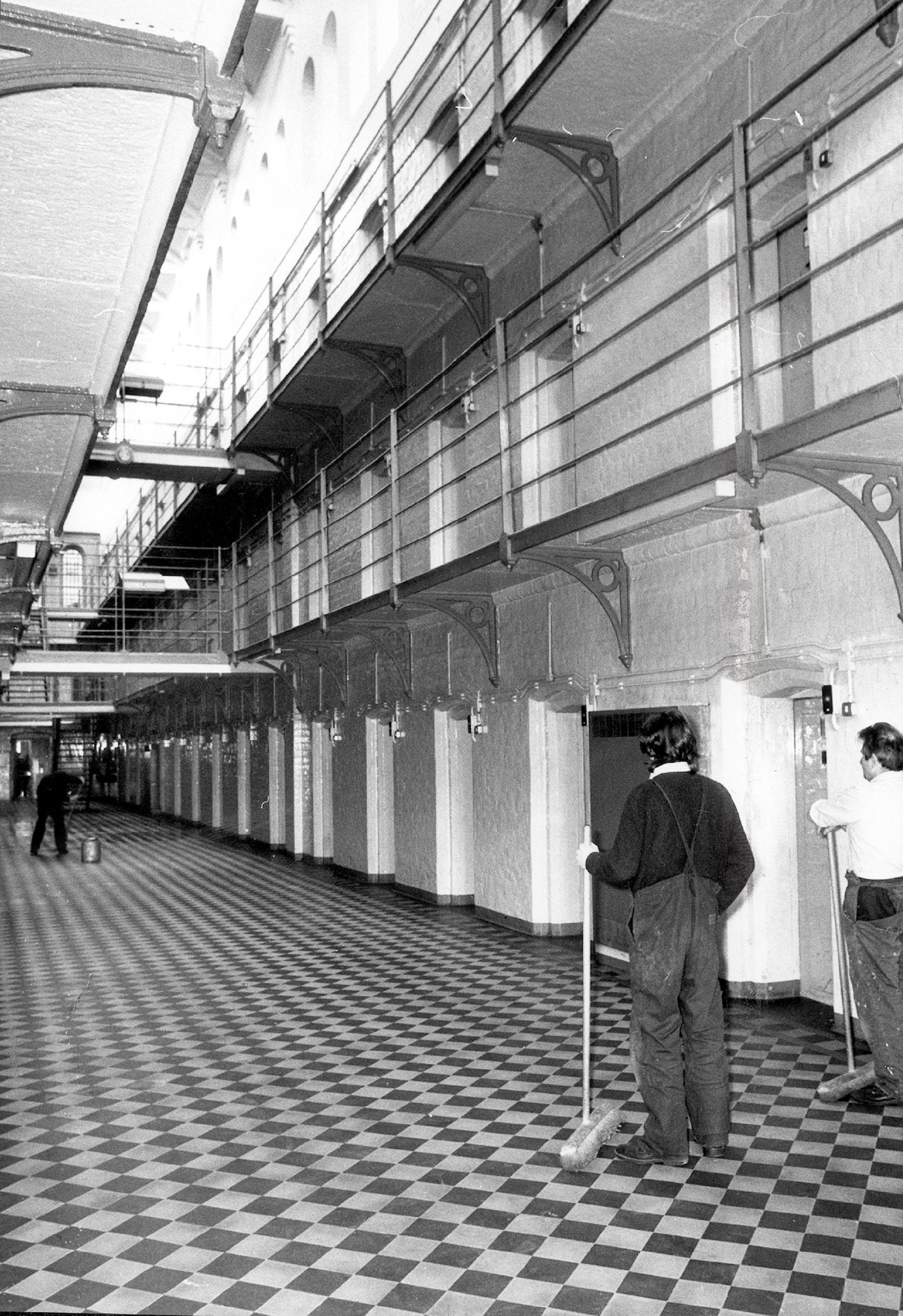

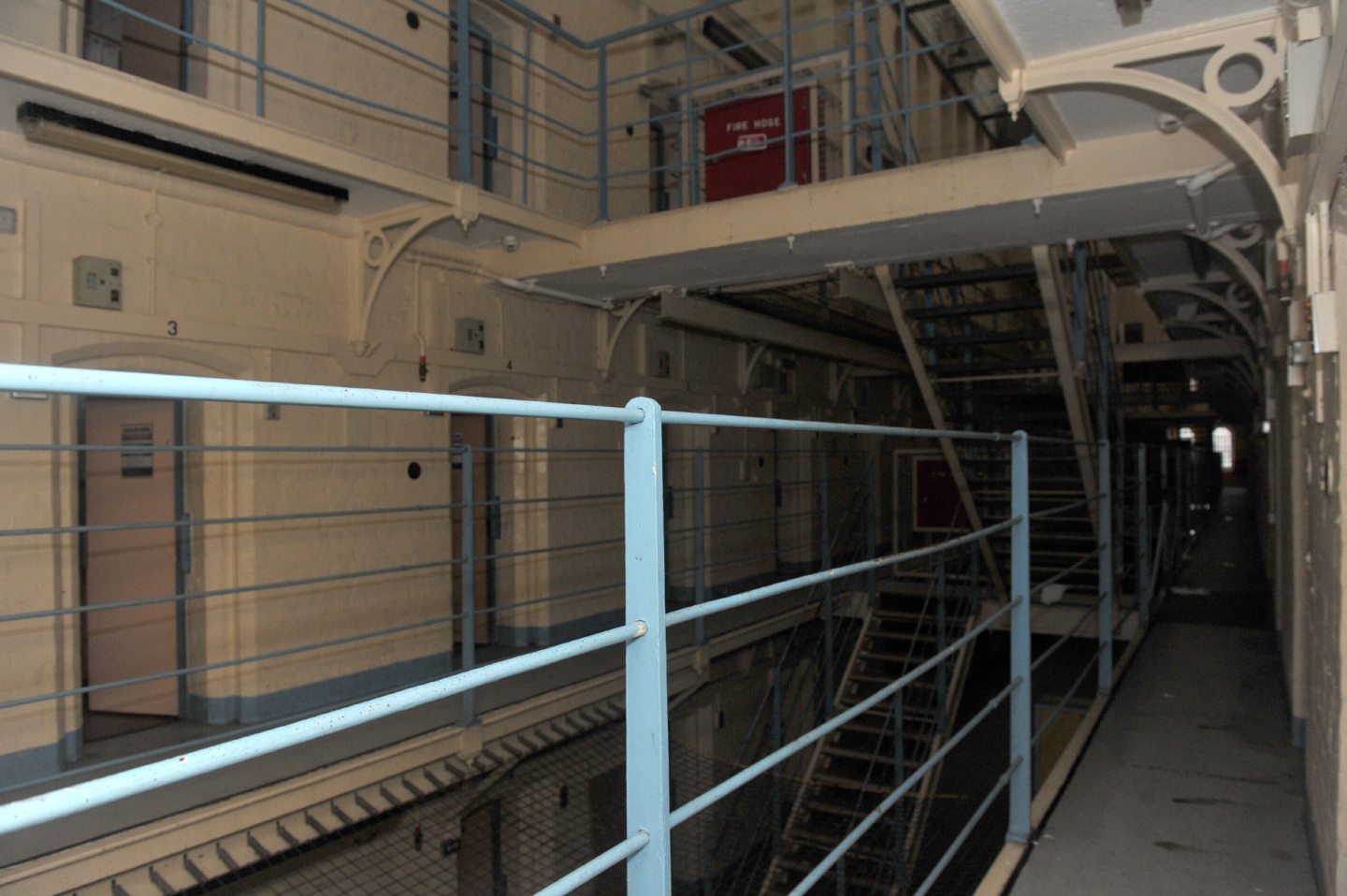

In the ’70s and ’80s, prisons were generally characterised by poor sanitation and overcrowding, with more prisoners and fewer staff.

But recreation and opportunities for prisoners to learn new skills was still important at Craiginches.

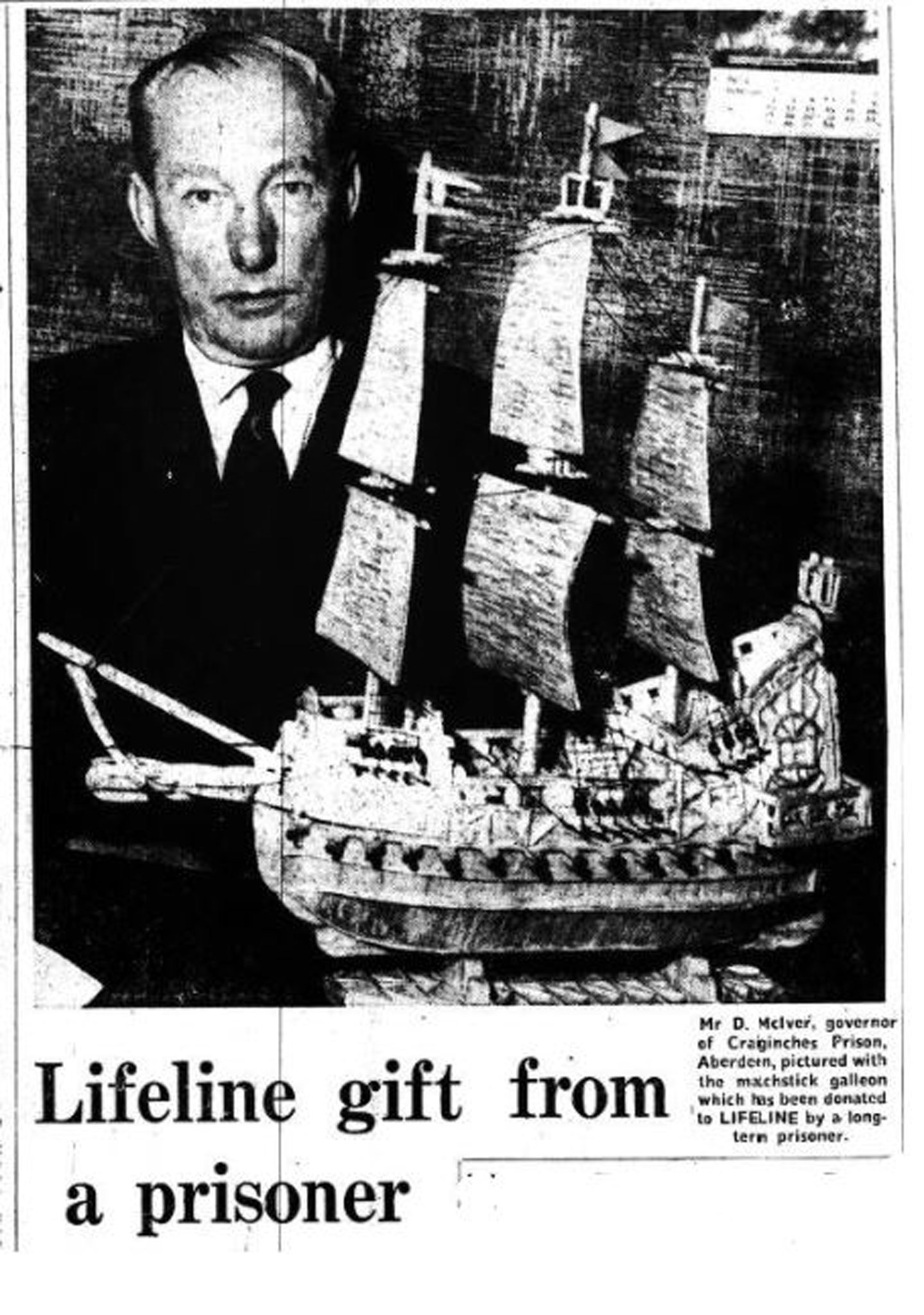

In 1973, the Evening Express ran ‘LIFELINE’ – a charity appeal to raise funds to buy more renal dialysis machines across Grampian.

The most unusual donation to the appeal was a beautiful scale model of a Galleon from a prisoner at Craiginches.

For five weeks, he constructed it entirely from used matchsticks admitting it took longer to collect the matches than it did to make the vessel.

Prison governor Mr McIver said the inmate was “using his spare time to benefit others”.

This holistic approach to prisoners continued in 1975, when Craiginches launched a Training for Freedom programme.

The scheme offered prisoners the opportunity to work outside the walls of the jail, and live a more normal life.

Community services such as beach clean-ups also aided their rehabilitation.

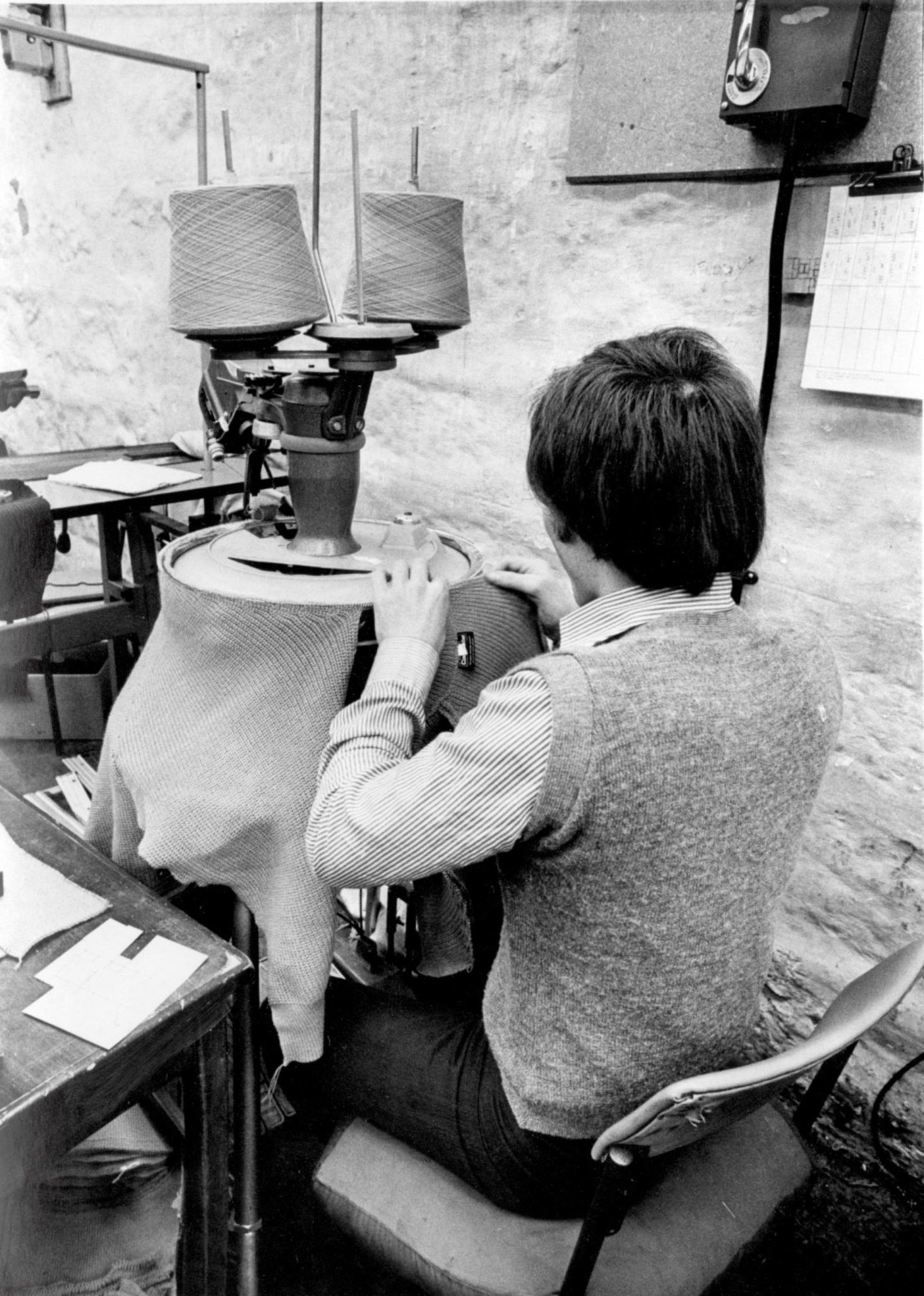

Craiginches was unique in the Scottish prison system because it was the only jail with a knitting shop.

It provided the whole prison service north of the border with knitted pullovers, trousers, pillowcases and towels.

Hapless Hogmanay escapees made headlines

But it was also unique, because it was home to every classification of prisoner – from lifers serving 30 years, to those serving short sentences under 18 months.

So, attempted breakouts and rooftop protests still punctuated life at Craiginches.

At Hogmanay in 1976, six daring inmates staged an escape attempt by tying blankets together to make a rope – a move that only landed them in court.

During their court appearance, it transpired the break-out bid was inspired by a radio show the prisoners had listened to earlier that day.

Ironically, it was about a prisoner who sought to escape to prove his innocence.

In court, the inmates’ own agent David Burnside admitted it was “more of a farce than a serious, well-planned escape bid”.

And added: “Two of the six virtually ran into the arms of prison officers.”

Later that year, a single prisoner took to the roof at Craiginches for three days and nights, he claimed because he wanted “peace and quiet”.

‘Prizners are people’

While in 1981, two prisoners spent time on the roof after escaping through a skylight in ‘A’ Hall.

A crowd of 50 residents gathered on neighbouring streets to watch as guards attempted to move the prisoners by hosing them.

Denying reports in the P&J that the officers had deliberately used water hoses in a bid to end the protest, the prison service said “the officers were simply testing the hoses”.

When quizzed about the need to test hoses at 9.25pm, a Scottish Office spokesman said prison authorities “had a duty” to ensure there was no danger of fire during such disturbances.

Unrest returned to the prison service in the late 1980s, when the infamous Peterhead Prison took place in January 1987.

It was Scotland’s longest jail siege, and ended only when the SAS were called in.

The following day, an incident flared at Craiginches, and prisoners unfurled a banner from a top floor window reading ‘Prizners are people”.

Protests at the prison weren’t far from the headlines in the late 1980s in Aberdeen.

Several prisoners went on hunger strike in October 1987 — hot off the back of nationwide sieges, conditions became stricter across the prison service with liberties curtailed.

But it ended in tragedy when one young man, with a history of kidney problems, died after six days of no food or fluids caused renal failure.

Prison celebrated centenary in 1991

By the time the 1990s came round, prisoners in Aberdeen were still slopping out – emptying buckets of human waste from their cells in lieu of proper toilets.

A Victorian throwback, it was a practice still ongoing when Craiginches celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1991.

But then-governor Leslie McBain was keen to see improvements, not only to sanitation and conditions, but to the way prisoners were treated.

By now, inmates were supported by a network of psychologists, psychiatrists, teachers, doctors, dentists and social workers.

Certain prisoners were also afforded the opportunity to enjoy the great outdoors with civic improvement work like path building at Burn O’ Vat near Aboyne.

But governor McBain felt his prison was mainly trouble-free and hoped improvements could be made to make life easier inside for prisoners.

He hoped electric power in cells would allow the men to have their own TVs.

He told the P&J: “Prisoners have to be treated as responsible human beings, and it’s important for the prison to try to develop their potential through classes, discussion and support.”

Princess Anne visited Craiginches the following year to mark the prison’s centenary and unveil a plaque bearing every governors since 1891.

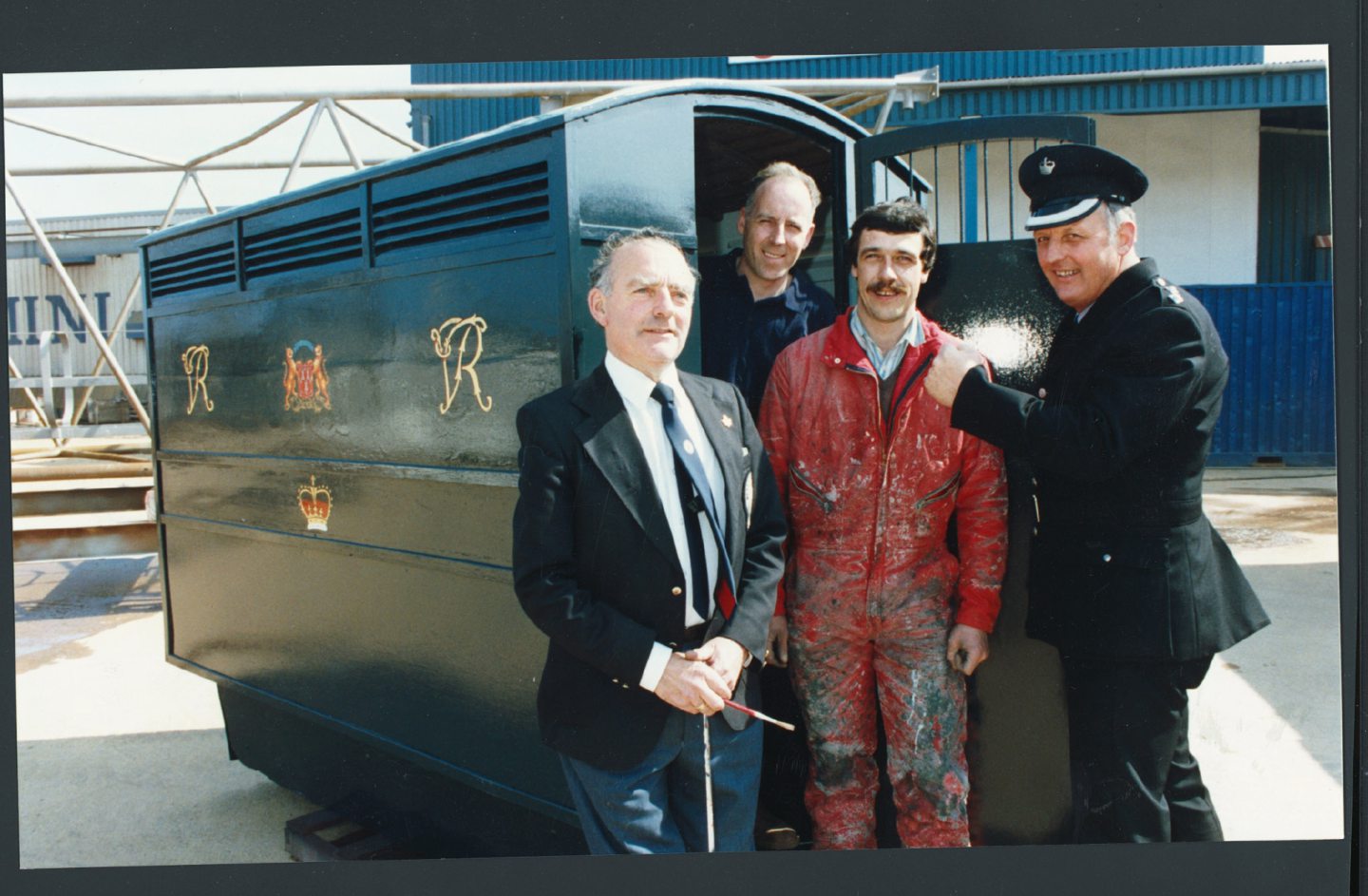

The prison’s own centenary project saw the officerse lovingly and painstakingly restore Craiginches’ original Black Maria – the wagon used to transport prisoners.

It took the starring role in a parade from Castlegate to Craiginches re-enacting the day prisoners were moved from the city centre to the new prison in 1891.

Victorian prison was no longer fit for purpose

But as the prison moved into the 21st Century, there were question marks over its future viability.

Peterhead and Craiginches prisons were Victorian institutions and little could be done to bring them up to a modern standard.

Plans were initially mooted to demolish Peterhead, because the nature of the building meant sanitation could not be fitted retrospectively.

Prisoners were still slopping out right up until its closure.

An inspection in 2005 concluded prisoners would never be able to live in decent conditions.

And the prison service began to receive human rights complaints from inmates.

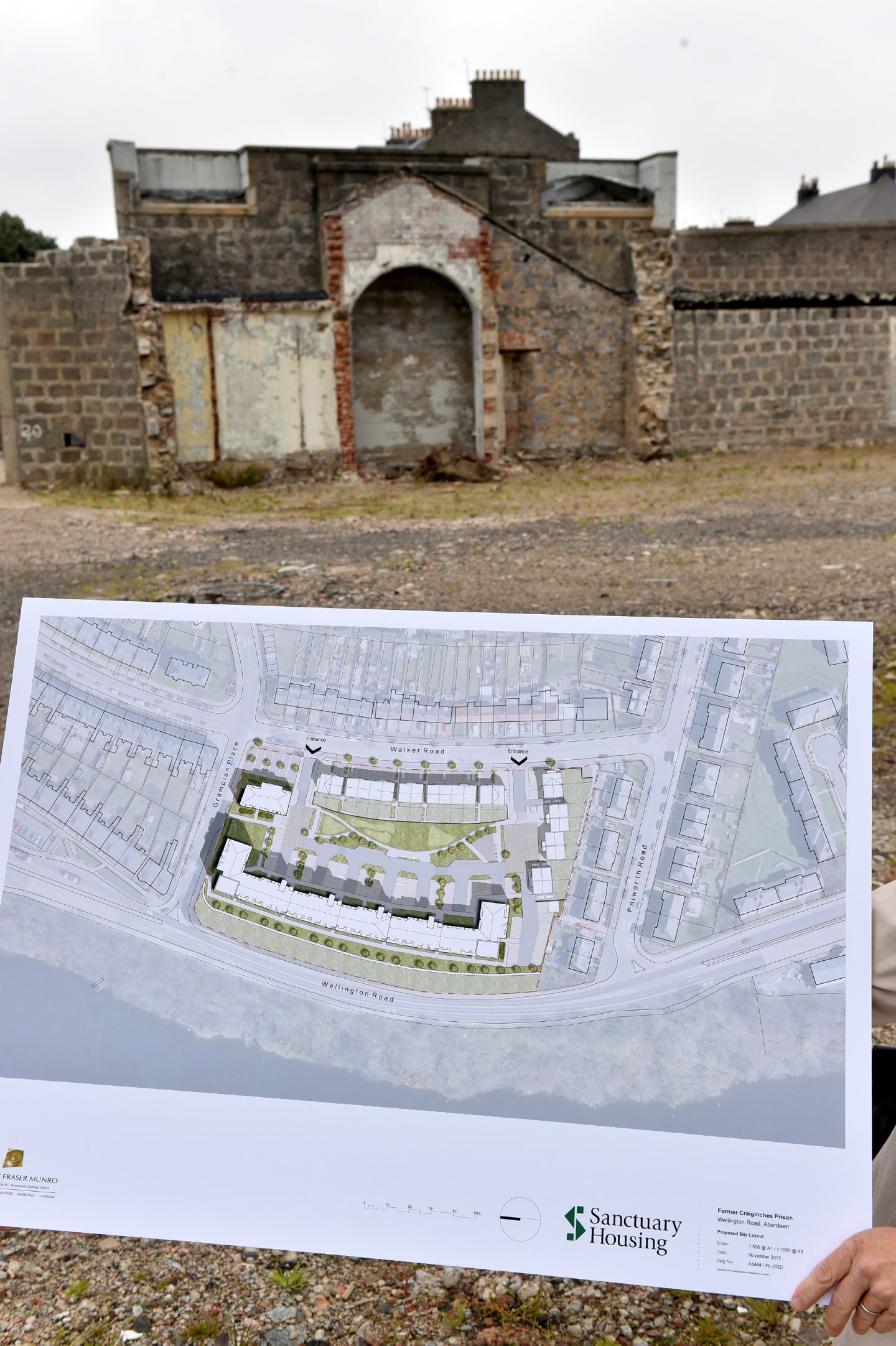

But Craiginches wasn’t much more suited to a modern justice system, so ultimately the decision was made to replace both with a ‘superjail’ in Peterhead.

Body of hanged man exhumed before demolition

Stuart Campbell, deputy governor of Craiginches, said it was a “real jail”, but one that belonged in the past.

Reflecting on its closure in January 2014, he said: “I think what we need to do is move on now. Jails are a unique part of society and Craiginches served its purpose.”

He paid tribute to his hard-working and “resilient” staff, and said he was looking forward to working in the new HMP Grampian, because it wouldn’t be overcrowded.

But before the demolition could begin at Craiginches, there was one last inmate yet to vacate the confines of the high prison walls.

More than half a century later, he was exhumed and cremated in a private ceremony at the crematorium on August 2 2014.

With the final prisoner freed from Craiginches, if only spiritually, the demolition work could begin to make way for affordable housing.

In pictures: The final years of Craiginches

If you like this, you might enjoy:

Conversation