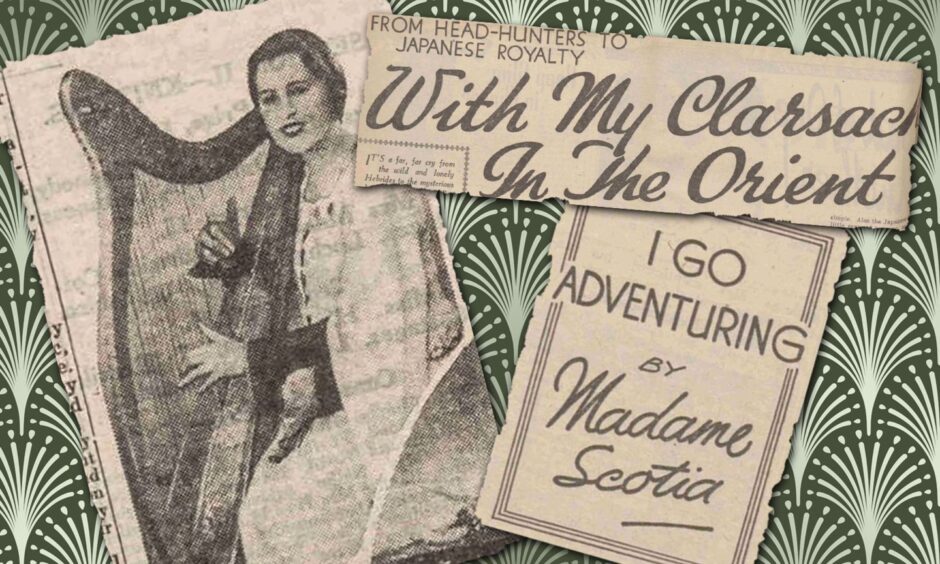

No part of the world was safe from the adventuring of Madame Scotia and ‘Harplet’, her clarsach in the 1930s.

Héloïse Russell-Ferguson, aka Madame Scotia, Madam Scrap, Jane and the Bardess of the Gorsedd, was born in Glasgow, to a family originally from Port Appin, Argyll.

She trained to high level in piano at the Royal Academy of Music in London from 1914-16 before going to teach in Washington DC.

There she had an epiphany which would shape her life.

She spotted a clarsach in a shop window and bought it instantly, convinced there was a strong bond between her and ‘Harplet’, as she called the instrument.

She went to the Hebrides to learn how to play and sing Gaelic songs, and then took them all over the world to share them with local and ex-patriate audiences.

But that bland statement goes nowhere near capturing her brand of eccentric creativity, her gung-ho spirit and remarkable capacity for being in the right place at the right time.

She writes of using a system of twigs to track down a lost party in the bush, of meeting real Sumatran head-hunters (not the corporate ones of today) and singing to a literally captive audience in New Zealand prisons.

In her writings, Madame Scotia tells of when she met the Japanese Emperor, sang to ward off big game while camping out withlocals’ in the African bush, and single-handedly saved everyone while visiting a flooded glow-worm cave in New Zealand.

And, ‘a mountain bears my name’, she writes from New Zealand, without too much evidence.

The Aberdeen People’s Journal decided to give reign to her colourful brand of travel writing over several weeks early in 1939.

On this day in 1939, she had penned a spread about her experiences in ‘the Orient’.

In the ‘Dutch Indies’ (now Indonesia), she visited Java, Bali and Sumatra.

In Java, her Hebridean songs “did their work thoroughly and several hundred people listened with unconcealed curiosity. Few had any idea of the ancient culture of Scotland. No-one had ever seen a Clarsach before.”

Clarsach could end war

And thrillingly, Madame Scotia read in the press the next morning ‘If this art could be understood by all today there would be no more war.’

She writes: “Surely the old Highland songs could gain no finer tribute than that.”

Also in Java Madame Scotia had to deal with a serious wardrobe malfunction.

“My bardic robes, unable to stand the strain of so many appearances, exposed to rough halls, tropical nights and the rigours of packing, suddenly rent themselves in twain!

Chez the modiste

“We presented ourselves doubtfully at a Javanese modiste’s in Sourabaya expecting many difficulties.

“A capable woman glanced at the robe.

“‘Yes I can do it. When would you like it?” she replied immediately, and in a few days a beautiful new robe was delivered by a smiling messenger clad in the bright sarong or skirt worn by the people.”

Encounters with Scots

One of the joys of Madame Scotia’s travelogues is that she records many of her encounters with ex-patriate Scots.

In Sumatra, her party dined with a Scot in his beautiful house with ‘deft, silent-footed boys to wait on him’.

The unnamed host turned out to be extremely homesick.

“‘Yes, it’s a grand place, Aberdeen!’ he sighed. “And do you ken Dundee?’

“The evening’s conversation ran on this line!” writes Madame Scotia cheerfully, having surely endured the dullest soiree of her tour.

But things took an unexpected turn.

A leaving surprise of a haggis in Sumatra

“The chief surprise came when we were leaving,” she writes.

“’Would you like a haggis to take along with you,’ he asked unexpectedly.

“’Haggis!’ we exclaimed, ‘here in Sumatra?’

“’Aye, here in my own kitchen,’ he laughed. ‘I always keep a supply. They tin them well these days,’ he added enthusiastically.

“And so we left, carrying a haggis in a tin, and our host was well pleased.”

In Japan, the Hebridean music seemed to transcend borders, despite Madame Scotia’s wish to sink through the floor in despair at the thought that her performance would fall on completely deaf ears.

“I mounted the platform. ‘These songs come from the Hebridean Isles,’ I announced in tinkling tones.’ (Madame Scotia had learned that the Japanese preferred women to speak that way.)

Rice bowl forgotten

“But wonder of wonders, the audience became charged with curiosity and stopped to stare at me and each other, bewildered. Rice bowl forgotten, and thatched cottage in its place. They understood!”

In Singapore she appears to have had great success with the local children despite her fears of a huge cultural abyss.

“The hall was packed. As I went on to the platform, I became aware of an immediate interest in Harplet.

“The children gazed at my robes… and they were so quick to realise Scotland and the position of the Western Isles. They learnt of the Gaelic tongue, and saw the rough moors and purple heather. I believe they even breathed the smell of the peat smoke.

“A brief account of the wanderings of Bonnie Prince Charlie seemed to interest the older boys especially. Their rapt faces were a study.

“We ended with the ‘Road to the Isles’ in which many children joined.”

Her memory is cherished

Despite her eccentricities, the work of Héloïse Russell-Ferguson is well remembered in pockets of the world she so charmingly conquered all those decades ago.

Her memory is particularly cherished in Brittany where she was appointed Bardess of Gorsedd and remains feted for her contribution to Celtic music, including introducing the clarsach.