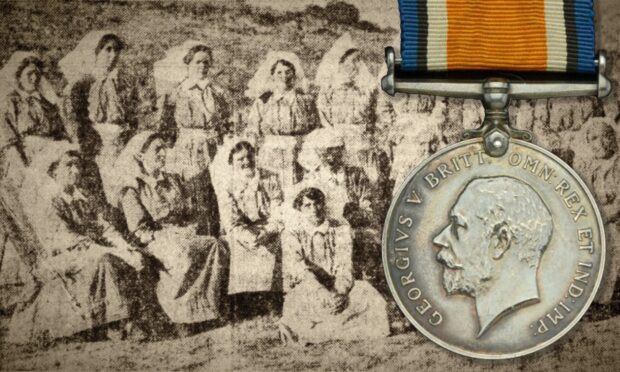

A First World War medal belonging to a pioneering Aberdeen woman who drove ambulances on the frontline is to go under the hammer.

Emily Robertson Duncan volunteered for the Scottish Women’s Hospitals and was posted to Salonika (now Thessaloniki) in Greece in 1917.

There, she was among the brave women chauffeuse ferrying injured soldiers to field hospitals – and defying gender stereotypes.

During the 1910s, women were still largely expected to stay at home and raise children, or work in menial jobs, and were certainly not encouraged to partake in the war effort abroad.

But women played a courageous, crucial, and often forgotten role on the 250-mile long Macedonian frontline in Greece.

Forgotten WW1 frontline in Macedonia

The Balkans theatre of war erupted after allied forces tried but failed to bring aid to Serbia, which was under attack from Bulgarian, German and Austro-Hungarian forces.

Serbia fell in October 1915.

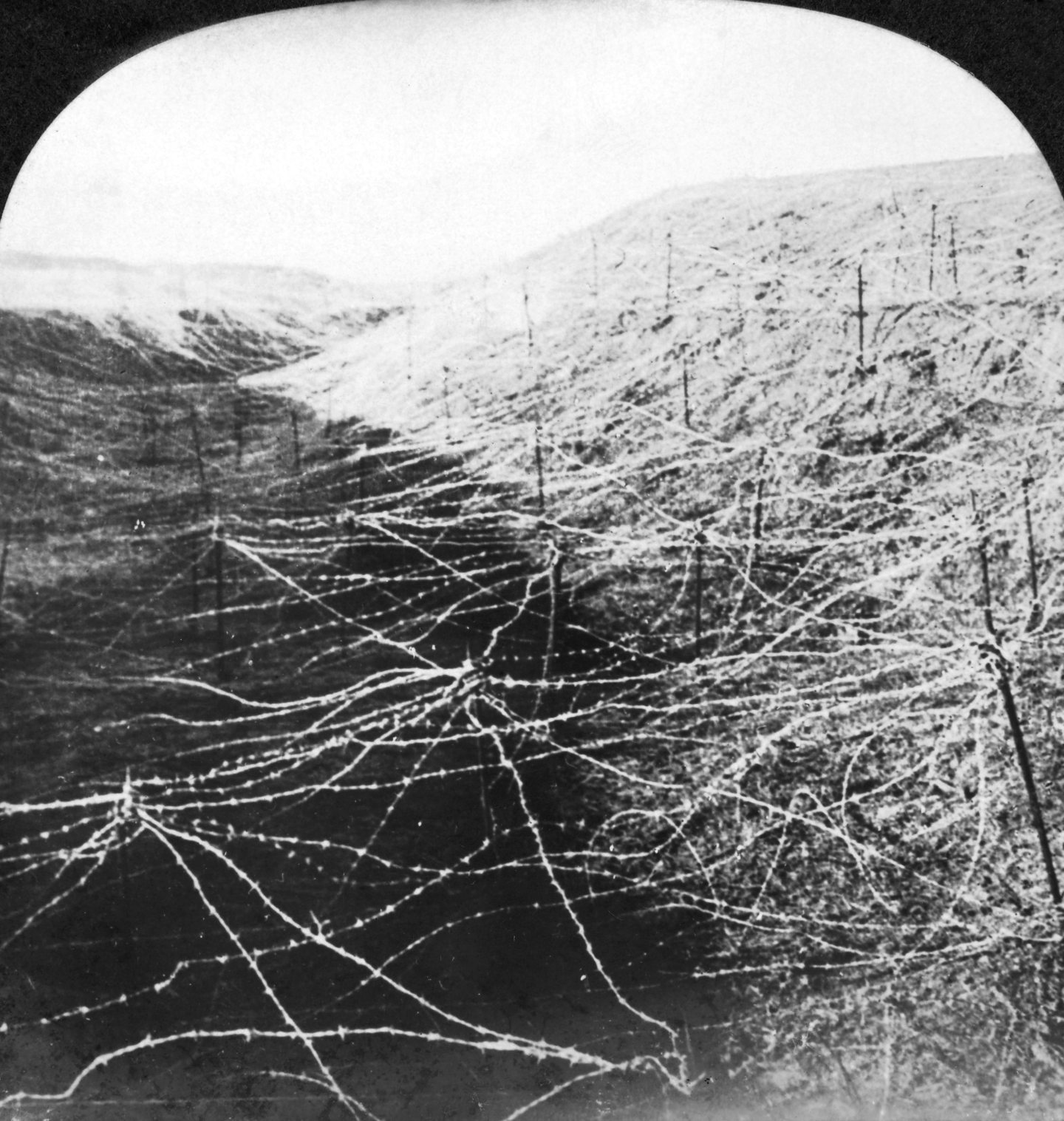

But conditions were brutal during the long campaign.

Soldiers faced the extremes of summer and winter weather conditions, and the British Salonika Force lost 20 times more men to malaria from mosquitos than battle injuries.

Without the Scottish Women’s Hospitals (SWH), many more would have died.

Hospital founder descended from illustrious Inverness family

The hospitals were established in Scotland in 1914 by surgeon and suffragist Elsie Inglis.

Born in India to Scottish parents, her family were descendants of the Inglis of Kingsmills, Inverness.

Elsie’s maternal grandfather was Reverend Henry Simson, minister at Chapel of Garioch Parish Church for 33 years.

But it was her father John Forbes David Inglis, a great believer in women’s education, that encouraged her to pursue a career in medicine.

Upon returning to Scotland, Elsie and her father set up a medical school for women.

As well as being Edinburgh’s leading female doctor, Elsie was also a founder member of the Scottish Women’s Suffrage Federation.

On the outbreak of war, Elsie quickly raised an army of medical volunteers and approached the war office to offer their services.

Scottish suffragists set up pioneering field hospitals

The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, quickly helped raise £50 million to set up the SWH.

Like Elsie, many of the women volunteers had been involved with the suffrage movement.

But their offer was rebuffed by the war office and Elsie was told to “go home and sit still”.

But she did not.

Instead Elsie approached allied governments who were only too happy to have SWH.

The pioneering women-only service not only featured female doctors and nurses, but female volunteers in non-medical roles like cooks, orderlies and ambulance drivers.

Women from all backgrounds volunteered side by side in demanding and harrowing circumstances, 24 hours a day.

In December 1914, Elsie travelled to Serbia where she was Chief Medical officer of the unit there, helping the country fight typhoid.

Aberdeen’s Emily Duncan answered call to arms in 1917

Following a period of stalemate on the Macedonian front, fighting ensued and the hospitals provided a vital support attached to the Serbian and French armies.

They set up hospital tents and treated both soldiers and civilians.

Many more women were drafted in, and one of those answering the call to arms in 1917 was Aberdeen’s Emily Robertson Duncan.

Hailing from Cults, her father was Aberdeen’s Procurator Fiscal Charles Duncan.

She was 34 and living at 20 Queen’s Road when she volunteered.

Emily spent two years driving ambulances for the French Red Cross in Salonika and later the SWH’s pioneering ‘Girton and Newnham’ Unit.

The terrain was tough, and drivers had a difficult task tackling tracks around the frontline.

SWH commissioner Dr Mary Blair wrote: “The roads are beyond belief and the driving of our girl chauffeurs is simply miraculous in its courage and skill.”

Tribute to ‘bravery and devotion’ of women chauffeurs in WW1

The summer of 1918 was particularly arduous for the nurses in the heat of Greece as they struggled to keep diseased patients cool.

Living and working in tents, the women practically performed miracles carrying out surgery and treating the wounded.

But the courage of the non-medical staff was also recognised, as highlighted by auctioneer Noonan’s of Mayfair.

Noonan’s is Britain’s leading auctioneer of militaria and medals.

A Press Association correspondent at the time reported: “‘It is only right to pay a tribute to the bravery and devotion of the chauffeuses of the Scottish Women’s Hospital attached to the Serbian Army, who take the ambulances as far as the cars can go along the precipitous paths in order to meet the wounded, and are constantly risking life and limb in this dangerous work, which requires skill as well as nerve.

“Yet young girls perform the journey sometimes twice daily, and often have to spend the night on the mountain side, as breakdowns are, unfortunately, too frequent in such bad country.”

While a Daily News reporter said “the large corps of the Scottish Women Motor Transport” earned the admiration of Romanians and Russians alike”.

Bearing in mind, this was at a time where driving had very much been considered the preserve of men.

But now, here were women with no right to vote back home, risking their own lives to save the lives of men in a warzone.

Aberdeen’s Emily Duncan reprised ambulance driver role in WW2

Emily survived the war and returned to Scotland in 1919 and was awarded the British War Medal.

The medal was awarded to all officers, men and women of British and Imperial forces for serving in the First World War.

But the actions of those volunteering with the SWH has been largely overlooked.

When the Second World War broke out, Emily was 56 and again stepped up to do her bit by working at St George’s Hospital in London.

The hospital was given over to the war effort and became part of the Emergency Hospital Service.

The 1939 register for Chelsea in London shows Emily worked for St George’s Air Raid Precautions’ Transport Service – likely reprising her role as an ambulance driver.

St George’s treated civilian air raid casualties and civilian sick.

Emily again survived the war and lived until 1963 when she died in Chelsea aged 80.

She is on the family grave at St Machar’s Cathedral in Aberdeen along with her illustrious parents and siblings.

Emily’s medal will go under the hammer today in London with an estimate of just £80-£100.

A common medal, it may not have much monetary value, but it is invaluable in keeping alive the forgotten stories of the brave women who stood up to men at home, to save soldiers abroad.

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

Conversation